Literatur

Bartetzko Urs, in: Niggli Marcel Alexander/Wiprächtiger Hans, Basler Kommentar, Strafrecht, 4. Aufl., Basel 2019; Benisowitsch Gregor, Die strafrechtliche Beurteilung von Bergunfällen, Diss. Zürich 1993; Berther Aldo/Wicky Michael: Schneesport Schweiz, Varianten und Touren, Belp 2010; Biefer Oliver, Recht auf Risiko? Wann gilt eine Aktivität als Wagnis?, in: WSL Berichte, Heft 34, Lawinen und Recht, Davos 2015; Bütler Michael, Gletscher im Blickfeld des Rechts, Diss. Zürich 2006; Dan Adrian, Le délit de commission par omission: éléments de droit suisse et comparé, Diss, Genf 2015; Donatsch Andreas/Godenzi Gunhilde/Tag Brigitte, Strafrecht I, Verbrechenslehre, 10. Aufl., Zürich 2022; Elsener Fabio/Wälchli Dominic, Pisten-Skifahren, in: Schneuwly Anne Mirjam/Müller Rahel (Hrsg.), Bergsportkommentar; Erni Franz, Unfall am Berg: wer wagt, verliert!, in: Klett Barbara (Hrsg.), Haftung am Berg, Zürich 2013, S. 15 ff.; Felber Franziska/Figini Nico, Gleitschirm, in: Schneuwly Anne Mirjam/Müller Rahel (Hrsg.), Bergsportkommentar; Gerber Andreas, Strafrechtliche Aspekte von Lawinen- und Bergunfällen unter Berücksichtigung der schweizerischen Gerichtspraxis, Diss. Zürich 1979; Harvey Stephan/Rhyner Hansueli/Schweizer Jürg, Lawinen – Verstehen, beurteilen und risikobasiert entscheiden, München, 2022; Harvey Stephan/Scheizer Jürg, Rechtliche Folgen nach Lawinenunfällen – eine statistische Auswertung, in: WSL Bericht, Heft 34, 2015, S. 63 ff.; Heinz Rey/Lorenz Strebel, in: Thomas Geiser/Wolf Stephan, Basler Kommentar, Zivilgesetzbuch II, 6. Aufl., Basel 2019; Kocholl Dominik, Führung und Führer am Berg: Verhältnis zum Bergsportler und "erlaubte" Führungstechniken, in: Klett Barbara (Hrsg.), Haftung am Berg, Zürich 2013, S. 145 ff.; Kuonen Stephanie, Alpinisme, in: Schneuwly Anne Mirjam/Müller Rahel (Hrsg.), Bergsportkommentar; Mathys Heinz Walter, Anklage und Verteidigung, in: Lawinen und Recht, Davos 1996; Munter Werner, 3x3 Lawinen, Risikomanagement im Wintersport, 6. Aufl., Bozen 2017; Müller Rahel, Haftungsfragen am Berg, Diss. Bern 2016 (zit. Haftungsfragen); Müller Rahel, Vorbemerkungen zu den Sportarten, in: Schneuwly Anne Mirjam/Müller Rahel (Hrsg.), Bergsportkommentar (zit. Bergsportkommentar); Niggli Marcel Alexander/Maeder Stefan, in: Niggli Marcel Alexander/Wiprächtiger Hans, Basler Kommentar, Strafrecht, 4. Aufl., Basel 2019; Niggli Marcel Alexander/Muskens Louis Frédéric, in: Niggli Marcel Alexander/Wiprächtiger Hans, Basler Kommentar, Strafrecht, 4. Aufl., Basel 2019; Peer Carlo, Jagdrecht, in: Schneuwly Anne Mirjam/Müller Rahel (Hrsg.), Bergsportkommentar; Portner Carlo, Rechtliches aus dem Bergführer-, Skilehrer- und Bergrettungswesen, Haldenstein 1988; Procter Emil et al., Burial duration, depth and air pocket explain avalanche survival patterns in Austria and Switzerland; Resuscitation 2016, 105, S. 173–176; Rudin Andy/Vonlanthen-Heuck Jennifer, in: Abt Thomas et al. (Hrsg.), Kommentar zum Waldgesetz, Zürich 2022; Schneuwly Anne Mirjam, Kitesurfen, in: Schneuwly Anne Mirjam (Hrsg.), Wassersportkommentar; Stiffler Hans-Kaspar, Schweizerisches Schneesportrecht, 3. Aufl., Bern 2002; Trechsel Stefan/Pieth Mark, Schweizerisches Strafgesetzbuch, Praxiskommentar, 4. Aufl., Zürich 2021; Vest Hans, Freispruch der im Bergunfall an der Jungfrau angeklagten militärischen Bergführer – ein Fehlurteil? in: Jusletter vom 27. September 2010; Vuille Miro, Wandern, in: Schneuwly Anne Mirjam/Müller Rahel (Hrsg.), Bergsportkommentar; Winkler Kurt/Hans-Peter Brehm/Jürg, Haltmeier: Bergsport Winter, Technik/Taktik/Sicherheit, 5. Aufl., Bern, 2021; Winkler Kurt/Schmudlach Günter/Degraeuwe Bart/Techel Frank, On the correlation between the forecast avalanche danger and avalanche risk taken by backcountry skiers in Switzerland, in: Cold Regions Science and Technology, 2021, S. 1 ff.

Materialien

Bergnotfälle Schweiz 2022, Zahlen und Auswertungen, Schweizer Alpen-Club SAC; Botschaft zu einem Bundesgesetz über Walderhaltung und Schutz vor Naturereignissen (Waldgesetz, WaG) vom 29. Juni 1988 (BBl 1988 III 173); Bericht der Kommission für Rechtsfragen des Nationalrates zur Parlamentarischen Initiative, Rahmengesetz für kommerziell angebotene Risikoaktivitäten und das Bergführerwesen vom 15. September 2009 (BBl 2009 6013 ff.); Bundesamt für Umwelt (BAFU): Wildruhezonen: Markierungshandbuch, Vollzugshilfe zur einheitlichen Markierung, Bern 2016; Ad-hoc-Kommission Schaden UVG, Empfehlungen zur Anwendung von UVG und UVV Nr. 5/83 Wagnisse vom 10. Oktober 1983, Totalrevision vom 16. Juni 2010, angepasst per 18. November 2016 und 27. Juni 2018; Empfehlungen zur Anwendung von UVG und UVV Nr. 5/83, ad hoc-Kommission Schaden UVG; Fachdokumentation «Schneeschuhwandern – Mehr Sicherheit auf grossem Fuss» von der Beratungsstelle für Unfallverhütung bfu vom November 2020; Erläuterungen zur Verordnung über das Bergführerwesen und Anbieten weiterer Risikoaktivitäten des BASPO (Risikoaktivitätenverordnung; SR 935.911), Version vom 13.08.2019, (zit. Erläuterungen RiskV); Kommentar zur Verordnung über das Bergführerwesen und Anbieten weiterer Risikoaktivitäten (Risikoaktivitätenverordnung, RiskV) des BASPO (zit. Kommentar RiskV); Faltbroschüre "Achtung Lawinen!", in: Kern-Ausbildungsteam «Lawinenprävention Schneesport», 8. Aufl. 2022; Rechtliche Stellung von Tourenleiterinnen und Tourenleitern des SAC; Schweizer Alpen-Club SAC, 2011; Schwierigkeitsskalen des Schweizer Alpen-Clubs SAC pro Bergsportdisziplin, Version September 2012; Richtlinien der Kommission Rechtsfragen Schneesportanlagen von Seilbahnen Schweiz, Die Verkehrssicherungspflichten auf Schneesportanlagen, Aufl. 2019 (zit. SBS-Richtlinien); Schweizerische Kommission für Unfallverhütung auf Schneesportabfahrten (SKUS), Schneeportanlagen: Richtlinien für Anlage, Betrieb und Unterhalt, Aufl. 2022 (zit. SKUS-Richtlinien); SwissSnowsports Association, Academy, Nr. 38, Belp 2022; SwissSnowsports Association, Academy, Nr. 33, Belp 2019; Swiss Snowsports Association, Academy, Nr. 24, Belp 2015; SwissSnowsports Association, Academy, Backcountry, Nr. 14, Belp 2009; WSL-Berichte, Schnee und Lawinen in den Schweizer Alpen, Hydrologisches Jahr 2021/2022, Heft 128, Davos 2023.

I. Allgemeines

Schneesportaktivitäten ausserhalb von gesicherten Skipisten – dem «freien» Schneesportgelände – erleben seit Jahren einen regelrechten Boom. So schön es auch ist, sich mit verschiedenen Schneesportgeräten bestenfalls in frischverschneites Gelände zu begeben, bergen solche Aktivitäten unweigerlich einerseits erhöhte Gefahren und führen andererseits auch zu einer erhöhten Belastung der Natur. In den Jahren 2018 - 2022 starben in der Schweiz bei Skitouren und Variantenabfahrten im jährlichen Mittel 32 Personen. Davon sind knapp 20 und mithin rund zweidrittel der Todesfälle auf Lawinenniedergänge zurückzuführen (vgl. SAC Bergnotfallstatistik 2022). Dies entspricht dem 20-jährigen Mittelwert von 21 Lawinentodesopfern (vgl. Statistik der tödlichen Lawinenunfälle der letzten 20 Jahre des WSL-Instituts für Schnee- und Lawinenforschung Davos, S. 40 f.). Die übrigen Todesfälle sind auf Abstürze, Gletscherspaltenstürze, Wechtenabbrüche oder Eis-/Steinschlag zurückzuführen. Aktuell werden, nicht zuletzt aufgrund meteorologischer Veränderungen, vermehrt Gletscherspaltenstürze beobachtet. So wurden im Jahr 2022 im Vergleich zum 10-jährigen Mittel mit 70 betroffenen Personen beinahe doppelt so viele Spaltenstürze verzeichnet. Davon sind 6 Spaltenstürze tödlich verlaufen, was mehr als eine Verdreifachung darstellt (vgl. SAC Bergnotfallstatistik 2022).

Ziel dieses Beitrags ist es, einen Überblick über die rechtlichen Aspekte von Schneesportaktivitäten ausserhalb von gesicherten Skipisten, d.h. im sogenannten «freien» Schneesportgelände, zu verschaffen. Während sich der vorliegende «Teil 1» neben den einleitenden Ausführungen den straf- und allgemeinen öffentlich-rechtlichen Aspekten widmet, fokussiert sich der «Teil 2» auf die privatrechtlichen Fragestellungen. Für Aktivitäten auf Skipisten wird auf den Artikel «Pisten-Skifahren» verwiesen (vgl. Elsener/Wälchli, passim).

A. Begriffsbestimmungen

Die Erscheinungsformen von Schneesportaktivitäten im «freien» Schneesportgelände und mithin ausserhalb von Skipisten sind heute vielfältig. Zu denken ist in erster Linie an die klassischen Tourenskis, der gleichen Familie entstammenden Telemarkskis oder ans Snowboard. Durch den technischen Fortschritt sind über die Jahre neue Aktivitäten entstanden. Nennenswert ist beispielsweise das «Speedflying», bei dem das Gleitschirmfliegen und das Skifahrern kombiniert werden (vgl. hierzu Felber/Figini, Rz. 10) oder auch das «Snowkiten», bei welchem Kiter*innen mit Skiern oder einem Snowboard über schneebedecktes Gelände oder gefrorene Gewässer fahren (vgl. hierzu Schneuwly, Kitesurfen, Rz. 2 und 24). Aufgrund der Vielfalt dieser Schneesportaktivitäten besteht hierzulande keine einheitliche Terminologie. Es ist namentlich die Rede von Skitouren, Pistenskitouren, Skihochtouren, Skibergsteigen, Freeriden, Variantenfahren, Back-Country, Off-Pist, Skimountaineering, Heliskiing, etc. Nachfolgend sind daher zunächst die Begriffe zu bestimmen, wie sie in der Schweiz für gewöhnlich in der Ausbildung der massgebenden Berufsgruppen verwendet werden und die teilweise Eingang ins Gesetz gefunden haben.

1. Touren mit Schneesportgeräten (Schneesporttouren)

Als «Touren» werden Aufstiege mit Tourenskis, Splitboards, Schneeschuhen oder ähnlichen Sportgeräten kombiniert mit einer Abfahrt verstanden (Erläuterungen RiskV, S. 3). Bei reinen Schneeschuhtouren erfolgt selbstredend und naturgemäss keine Abfahrt, sondern ein Abstieg. In zeitlicher Hinsicht können sämtliche Schneesporttouren mehr oder weniger lang dauern – von wenigen Stunden bis hin zu mehreren Tagen. Bei mehrtägigen Touren wird in der Regel in Berghütten, Hotels, Zelten oder einem Biwak (Übernachten ohne Zelt unter freiem Himmel, in einem Iglu oder in einer Schneehöhle, vgl. Merkblatt Schweizer Alpen-Club «Campieren und Biwakieren in den Schweizer Bergen») übernachtet. Dies kann insofern relevant sein, als für solche organisierten «Pakete» (Tour und Übernachtung) das Pauschalreisegesetz punktuell zur Anwendung gelangen kann (vgl. Art. 1 Pauschalreisegesetz [Bundesgesetz über Pauschalreisen vom 18. Juni 1993, SR 944.3]; Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 298, 333 f., 339 ff.; Nosetti, Rz. 221 ff.; Wiede, Reiserecht, Zürich, 2014, Rz. 489 ff.).

Der Begriff «Schneesporttouren» bezeichnet im Sinne eines Oberbegriffs sämtliche Touren, die mithilfe von Schneesportgeräten unternommen werden. Der vorliegende Beitrag fokussiert sich auf Skitouren (inkl. Varianten), wobei die Ausführungen grundsätzlich auch bei Touren mit anderen Schneesportgeräten Geltung erlangen.

a. Skitour

Tourenskis mit Steigfellen ermöglichen einen vertikalen Aufstieg mit Abfahrt. Skitouren können sowohl im «freien» Schneesportgelände als auch innerhalb des gesicherten Schneesportgeländes, d.h. auf Skipisten unternommen werden.

b. Telemarktour

Telemarkskis mit Steigfellen ermöglichen ebenfalls vertikale Aufstiege mit Abfahrten. Sie unterscheiden sich von den Tourenskis im Wesentlichen dadurch, dass in der Abfahrt nicht der ganze Schuh in der Bindung fixiert ist, sondern einzig die Schuhspitze, was zu einer besonderen Abfahrtstechnik führt. Telemarktouren können ebenfalls sowohl im «freien» Schneesportgelände als auch innerhalb des gesicherten Schneesportgeländes unternommen werden.

c. Snowboardtour

Während Snowboardfahrer*innen bis vor einigen Jahren noch mühselig mit Schneeschuhen und mit auf dem Rucksack aufgebundenem Snowboard vertikale Aufstiege in Angriff nehmen mussten, bedienen sie sich heutzutage regelmässig eines «Splitboards». Dieses in der Länge teilbare Snowboard ermöglicht dank einem raffinierten System und Steigfellen einen relativ bequemen Aufstieg mit zwei «Skiern» und nach Zusammensetzen beider Skier zu einem «Board» eine Abfahrt mittels Snowboards. Snowboardtouren, mit Schneeschuhen oder Splitboard, werden ebenfalls sowohl im «freien» Schneesportgelände als auch innerhalb des gesicherten Schneesportgeländes praktiziert.

d. Schneeschuhtour

Mit Schneeschuhen werden ebenfalls Touren unternommen. Die Mehrheit der Schneeschuhläufer*innen bewegen sich im gesicherten Schneesportgelände auf ausgeschilderten Schneeschuhtrails. Schneeschuhtouren können aber ebenfalls im «freien» Gelände unternommen werden (vgl. zum Ganzen auch Fachdokumentation «Schneeschuhrouten – Mehr Sicherheit auf grossem Fuss» der Beratungsstelle für Unfallverhütung bfu).

2. (Winter-)Hochtouren mit Schneesportgeräten

Bei Hochtouren, sei dies im Winter oder Sommer, werden typischerweise Gletscher und damit alpines Hochgebirge betreten. Zudem wird nach einem Aufstieg regelmässig das letzte Stück auf einen Berggipfel zu Fuss bewältigt, d.h. ohne Schneesportgerät und mittels alpiner Technik (Verwendung Seilsicherung, Pickel und Steigeisen). Während im voralpinen Gelände die Gefahren bei Schneesporttouren hauptsächlich auf Lawinen beschränkt sind, müssen bei hochalpinen Touren zusätzliche damit einhergehende Gefahren, insbesondere die Absturz- bzw. Spaltensturzgefahr und Steinschlag- bzw. Eisabbruchgefahr, beachtet werden.

3. Varianten mit Schneesportgeräten (Freeriden)

Als Variantenabfahrten gelten mit Bergbahnen erschlossene und mit Schneesportgeräten durchgeführte Abfahrten, die ausserhalb des Verantwortungsbereichs der Betreiber von Skilift- und Seilbahnanlagen liegen (vgl. Legaldefinition von Art. 3 Abs. 2 der RiskV). Neudeutsch wird hierfür auch der Begriff «Freeriden» verwendet. Charakteristisch für Variantenabfahrten ist die Verwendung von Skilift- oder Seilbahnanlagen mit gegebenenfalls einem kurzen Fussaufstieg zum Ausgangspunkt der Abfahrt, ohne hierfür jedoch – und im Gegensatz zum Touren – eine Aufstiegshilfe zu verwenden. Variantenabfahrten enden sodann auch wiederum im erschlossenen (Ski-)Gebiet, so dass es keinem erneuten Aufstieg mittels Aufstiegshilfen bedarf (Erläuterungen RiskV, S. 4; Harvey/Rhyner/Schweizer, S. 286).

Die Unterscheidung zwischen Variantenabfahrten und Schneesporttouren ist insbesondere für die Kompetenzregelung des kommerziellen Anbietens solcher Aktivitäten von Bedeutung (siehe hiernach Rz. 17 f.).

4. Freies vs. gesichertes Schneesportgelände

Wegen Haftungsfragen ist strikt zwischen dem innerhalb und ausserhalb des Verantwortungsbereichs der Betreiber*innen von Skilift- und Seilbahnanlagen liegenden Schneesportgelände zu unterscheiden. Für ersteren Bereich kommt den Bergbahnbetreiberinnen eine Verkehrssicherungspflicht zu (vgl. hierzu Elsener/Wälchli, Rz. 26 ff.). Im vorliegenden Beitrag sind die Bereiche ausserhalb des Verantwortungsbereichs von Bergbahnbetreiberinnen relevant. Dieses sogenannte «freie» Schneesportgelände befindet sich abseits der markierten Pisten (blau, rot oder schwarz markiert) und Abfahrten (gelb markiert) und wird weder gegen alpine Gefahren (Lawinen- und Absturzgefahr) gesichert noch kontrolliert (vgl. auch Urteil des Bundesgericht 6B_403/2016 vom 28. November 2017 E. 3.2.2). Zu diesem «freien» Schneesportgelände zählen insbesondere auch die Variantenabfahrten und die sogenannten «wilden Pisten». Zu Letzteren gehören viel befahrene Bereiche zwischen Skipisten, die als Abkürzungen oder Verbindungen verwendet werden und dadurch den Charakter von Pisten erhalten (vgl. zum Ganzen Rz. 5 ff., 11, 34 und 35 SKUS-Richtlinien sowie Rz. 8, 42-49, 53, 176 SBS-Richtlinien). Negativ ausgedrückt ist somit alles «freies» Schneesportgelände, was nicht als markierte Schneesportfläche den Schneesportlern*innen zur Verfügung gestellt wird und den mehr als 2 Meter über den Pistenrand hinausgehende Bereich tangiert (SKUS-Richtlinien, Rz. 23 f.; SBS-Richtlinien, Rz. 107).

Die Unterscheidung zwischen dem «freien» Schneesportgelände und jenem innerhalb des Verantwortungsbereichs von Bergbahnbetreiberinnen ist von ausserordentlich grosser Bedeutung. Schneesportaktivitäten im «freien» Schneesportgelände erfolgen auf eigenes Risiko und grundsätzlich in Eigenverantwortung (vgl. SKUS-Richtlinien, Rz. 3 und 35; SBS-Richtlinien, Rz. 122 f., 45, 182; BGE 115 IV 189 E. 3 b).

5. Heliskiing

Unter Heliskiing versteht man die Beförderung von Schneesportlern*innen mittels Helikopters oder seltener mittels Flugzeuges zu einem gesetzlich klar definierten Gebirgslandeplatz als Ausgangspunk für eine anschliessende Schneesportabfahrt in -– wenn immer möglich -– unverspurten Hängen. Diese Schneesportaktivität wird für gewöhnlich im «freien» Schneesportgelände praktiziert (vgl. Rz 15, II. B.4 hiernach).

B. Akteure

Die Akteure im Bereich von Schneesportaktivitäten im «freien» Gelände sind vielfältig. Solche Aktivitäten können mit Berufspersonen, innerhalb eines (Sport-)Vereins oder Freundeskreis, aber auch im Rahmen des Militärs unternommen werden.

1. Berufsmässige Akteure

a. Bergführer*innen

Bergführer*innen sind Personen, die aufgrund einer vorgeschriebenen Ausbildung und Berufsprüfung den eidgenössischen Fachausweis erlangt haben (Art. 4 Abs. 1 lit. a RiskG). Sie sind berechtigt, Gäste gegen Entgelt in gebirgigem oder felsigem Gelände, wo Lawinengefahr, Absturz-/Abrutschgefahr und Stein-/Eisschlag besteht, zu führen. Diese Tätigkeit ist generell bewilligungspflichtig und berechtigt vorbehaltlos zur Ausübung sämtlicher unter das Risikogesetz fallenden Schneesportaktivitäten (Art. 3 RisG und Art. 4 Abs. 1 i.V.m. Art. 3 Abs. 1 lit. a–h RiskV). Bergführer-Aspirant*innen dürfen bewilligungspflichtige Aktivitäten führen, sofern diese unter der direkten oder indirekten Aufsicht und Mitverantwortung eines Bergführers bzw. einer Bergführerin erfolgt (Art. 1 lit. a i.V.m. Art. 5 RiskV). Diese praktischen Führungserfahrungen sind sodann auch Pflicht, um den Fachausweis zu erlangen.

b. Schneesportlehrer*innen

Schneesportlehrer*innen sind Personen, die aufgrund einer vorgeschriebenen Ausbildung und Berufsprüfung den eidgenössischen Fachausweis erlangt haben (Art. 5 Abs. 1 lit. a RiskG). Sie sind über ihre (Haupt-)Tätigkeit des berufsmässigen Schneesportunterrichts in verschiedenen Disziplinen (Ski, Snowboard, Telemark, und Langlauf) innerhalb des gesicherten Skipistenbereichs mit der entsprechenden Bewilligung zusätzlich berechtigt, Gäste gegen Entgelt auch im «freien» Schneesportgelände zu führen. Im Gegensatz zu Bergführer*innen ist diese Aktivität auf Ski- und Snowboardtouren bis maximal zur Schwierigkeit «wenig schwierig» gemäss Skitourenskala des SAC beschränkt. Ebenso sind sie berechtigt, Variantenabfahrten bis maximal zur Schwierigkeit «schwierig» zu führen, sofern keine Absturzgefahr besteht. Schliesslich können sie auch anspruchsvolle Schneeschuhtouren bis zur Schwierigkeit «WT3» gemäss Schneeschuhtourenskala des SAC unternehmen (vgl. zum Ganzen Art. 3 RiskG und Art. 7 Abs. 1 i.V.m. Art. 3 Abs. 1 lit. c–e RiskV). Gänzlich untersagt – und damit Bergführern*innen vorbehalten – sind über die vorgenannten Schwierigkeitsgrade hinausgehende Skitouren und Varianten sowie solche, bei denen Gletscher betreten oder technische Hilfsmittel wie Pickel, Steigeisen oder Seile zu Sicherheitszwecken verwendet werden müssen (Art. 7 Abs. 1 RiskV). Gletscherabfahrten wie beispielsweise jene von der Diavolezza nach Morteratsch sind hingegen für Schneesportlehrer*innen erlaubt, sofern sie durch die Betreiber*innen von Skilift- und Seilbahnanlagen geöffnet sind und mithin Abfahrten darstellen (vgl. Bst. A, Ziff. 4 hiervor). Schliesslich ist faktisch auch das kommerzielle Führen im Rahmen des Heliskiings Bergführern*innen vorbehalten. Einerseits befinden sich die meisten hierfür geeigneten Gebirgslandeplätzen im hochalpinen Gebirge und mithin auf Gletschern. Andererseits schreiben die Helikopterunternehmungen die Begleitung eines Bergführers bzw. einer Bergführerin regelmässig vor.

c. Wanderleiter*innen

Wanderleiter:innen sind Personen, die aufgrund einer vorgeschriebenen Ausbildung und Berufsprüfung den eidgenössischen Fachausweis erlangt haben (Art. 8 RiskV, vgl. auch Vuille, Rz 15). Sie sind zum (berufsmässigen) Führen von Kund:innen auf Schneeschuhtouren bis zum Schwierigkeitsgrad WT3 gemäss SAC Schneeschuhtourenskala befugt, sofern keine Gletscher überquert werden oder technische Hilfsmittel (Pickel, Steigeisen oder Seile) verwendet werden müssen, um die Sicherheit der Geführten zu gewährleisten. Schneeschuhtouren ab Schwierigkeitsgrad WT4 gemäss SAC Schneeschuhtourenskala bleiben den Bergführer*innen vorbehalten (Erläuterungen RiskV, S. 11).

2. Nicht berufsmässige Akteure

Mangels Berufs- bzw. Gewerbsmässigkeit unterstehen die Schneesportaktivitäten im Rahmen von nicht gewinnorientierten Organisationen wie beispielsweise des SAC, anderweitigen Sportclubs und -vereinen, Bildungsinstitutionen und staatlichen Sportförderprogramms «Jugend+Sport» (nachfolgend: J+S) nicht dem RiskG. Entsprechend bedürfen sie keiner Bewilligung. Der Gesetzgeber geht bei diesen Organisationen von der Prämisse aus, dass interne Strukturen und Vorgaben die Sicherheit der Teilnehmenden genügend garantieren (Art. 2 Abs. 2 RiskV).

a. Tourenleiter*innen

SAC-Tourenleiter*innen, Tourenleiter*innen von Sportclubs und -vereinen sowie J+S-Leiter*innen werden als solche ausgebildet. Sie werden zur Führung und zum Unterrichten von Gruppen bestimmt und aufgrund ihrer durchlaufenen Ausbildung dazu auch befähigt. Im Bereich des SAC führt der Zentralverband für die Tourenleiter*innen Tourenleiterkurse in verschiedenen Disziplinen durch. Zum Leiten von Gruppen im voralpinen Gelände mit Skiern, Snowboard oder Schneeschuhen bietet der Zentralverband den Tourenleiterkurs Winter 1 und für Skihochtouren im Hochgebirge den Tourenleiterkurs Winter 2 an. Zugleich verpflichtet er seine Sektionen, nur ausgebildete Tourenleiter*innen einzusetzen (vgl. hierzu auch Reglement des SAC-Zentralverbandes «Aus- und Fortbildungspflicht SAC-Tourenleiter*innen»).

Aufgrund der zivilrechtlichen Vereinsautonomie ist es den einzelnen SAC-Sektionen, aber auch den übrigen Sportclubs und -vereinen, sodann weitestgehend selber überlassen, interne Kompetenzregelungen aufzustellen. Die meisten SAC-Sektionen sehen eine (interne) Bewilligungspflicht der ausgeschriebenen Schneesporttouren vor. Im Rahmen des gesetzlich normierten Sportförderprogramm J+S bedarf es für die Durchführung von Skitouren zwingend eines J+S Skitourenleiterkurses, wobei jeweils mindestens eine Leitungsperson über den Zusatz «Kursleiter*in» verfügen muss. Sämtliche Skitouren sind zudem bewilligungspflichtig (Art. 4 Abs. 1 lit. a, Art. 20 und Anhang 3 Ziff. 3 Verordnung des BASPO über «Jugend+Sport» vom 1. Dezember 2022, SR 415.011.2).

b. «Faktische» Führer*innen und Gefahrengemeinschaften

Die Frage nach einer allfälligen «faktischen» Führerschaft bzw. Gefahrengemeinschaft stellt sich primär dann, wenn nicht durch professionelle Akteure geführte Schneesporttouren, insbesondere im Familien- oder Freundeskreis, unternommen werden.

Als «faktische» Führer*innen gelten Personen, die aufgrund ihrer alpinen Erfahrung und ihres alpinistischen Könnens weniger erfahrene Personen zum Mitgehen ins Gebirge veranlassen, die erforderlichen Entscheide treffen und damit tatsächlich, d.h. faktisch, die Führungsrolle übernehmen. Als wesentliches Merkmal gilt, dass die solcherart «Geführten» ihre eigene Entscheidungsfreiheit aufgeben und die Sorge für ihre Sicherheit dem/der faktischen Führer*in anvertrauen, so dass ein gewisses Subordinationsverhältnis entsteht (vgl. BGE 83 IV 9 E. 1; BGE 100 IV 210 E. 2b; Stiffler, Schweizerisches Schneesportrecht, Rz. 750 f., S. 182; Praxiskommentar StGB Trechsel/Pateh-Moghadam, Art. 11 N 13; Kocholl, S. 145 f. und 150; Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 244 f., S.86; Gerber, S. 135 f. und 146 f.).

Keine faktische Führerschaft kennt die sogenannte Gefahrengemeinschaft, bei der sich etwa gleich starke und gleich erfahrene Schneesportler*innen zusammentun, um ihre risikobehaftete Tätigkeit gemeinsam auszuüben. Da in einer solchen Konstellation niemand eine eigentliche Führungsrolle ausübt und mangels Wissens- und Erfahrungsvorsprungs auch gar nicht ausüben kann, hat jeder gleicherweise und in eigener Verantwortung allfällige Gefahren abzuschätzen. Aufgrund der straflosen eigenverantwortlichen Selbstgefährdung bzw. -tötung ist im Falle eines Unfalles auch keiner als faktische Führungsperson verantwortlich (vgl. Beschwerdeentscheid des Kantonsgerichts Graubünden BK 07 27 vom 16. August 2007, E. 4b; Stiffler, Schweizerisches Schneesportrecht, Rz. 751, S. 182; Gerber, S. 110 f. und 137 f.; Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 214, S.74).

Die selbst in Fachkreisen oftmals gehörte Aussage, dass im Rahmen von Gruppen im Freundes- oder Familienkreis automatisch die erfahrenste Person bzw. jene mit der höchsten Ausbildung als «faktischer Führer» hafte, erweist sich in dieser Absolutheit als unzutreffend. Damit der faktischen Führerschaft diese Rolle zukommt, bedarf es zwingend einer vorgängigen expliziten oder konkludenten Übernahme der (Führungs-)Verantwortung (vgl. hierzu auch BGE 141 IV 249, E. 1.4.1 m.w.H.; Dan, Rz. 202 und 256 ff.). Aufgrund der Möglichkeit der konkludenten Verantwortungsübernahme empfiehlt es sich, die Rollenverteilung vor Aufbruch zu einer Tour zu klären.

3. Militärische Führer*innen

Die Schweizer Armee ist naturgemäss hierarchisch organisiert und strukturell in Verbände auf verschiedenen Stufen gegliedert (aufsteigend: Trupp, Gruppe, Zug, Einheit wie z.B. Kompanie, Truppenkörper wie z.B. Bataillon sowie dem grossen Verband wie bspw. Brigade). Jeder Verband wird durch eine vorgesetzte Person geführt, die für sämtliche Angehörigen der Armee dieses Verbands verantwortlich ist (Art. 18 f. Dienstreglement der Armee vom 22. Juni 1994, SR 510.107.0 [DRA]). Die vorgesetzte Person hat stets für das Wohl und den Schutz seiner Unterstellten zu sorgen und diese nicht unnötig Risiken und Gefahren auszusetzen. Bei der Vorbereitung ihrer Entschlüsse kann sie ihre Unterstellten beiziehen, verantwortet diese indessen alleine (Art. 12 DRA). Die Unterstellten sind ihrerseits zu Gehorsam verpflichtet (Art. 21 DRA).

Militärische Führer*innen im Schneesportwesen sind regelmässig zivil ausgebildete Bergführer*innen oder besonders geschulte Angehörige der Armee. Zu Letzteren gehören insbesondere die Gebirgsspezialisten, welche durch das Kompetenzzentrum Gebirgsdienst der Armee in Andermatt spezifisch für das winterliche und sommerliche (Hoch-)Gebirge ausgebildet und hierfür eingesetzt werden.

II. Öffentlich-rechtliche Regelungen

A. Grundsatz des freien Zugangs zur Natur

In der Schweiz besteht ein grundsätzliches Recht auf freien Zugang zur Natur. Die massgeblichen Rechtsgrundlagen befinden sich im Zivilgesetzbuch und dem Bundesgesetz über den Wald vom 4. Oktober 1991 (Waldgesetz, SR 921.0). Art. 699 Abs. 1 ZGB gewährt ein allgemeines Betretungsrecht von Wald und Weide und war bis zum Inkrafttreten des Waldgesetzes die einzige Rechtsgrundlage für diesen Zugang (Kommentar zum WaG Rudin/Vonlanthen-Heuck, Kommentar Art. 14 N 1). Das heute aus Art. 14 Abs. 1 WaG fliessende Betretungsrecht des Waldes umfasst nicht nur das Betreten des Waldes zu Fuss, sondern auch das Befahren des Waldes mit Skiern oder sonstigen Schneesportgeräten, sowohl auf Waldstrassen als auch im übrigen Wald (BSK ZGB II-Rey/Strebel, Art. 699 N 13). Die über den Wald bzw. die Weide hinausgehende Zutrittsberechtigung für das kulturunfähige Land, wie beispielsweise Felsen, Firnen und Gletschern im Sinne von Art. 644 ZGB, lässt sich nach der Rechtsprechung und Lehre per analogiam aus Art. 699 ZGB ableiten (BGE 141 III 195, E. 2.6; Bütler, S. 28 und 54 f.).

B. Einschränkungen des Zugangs zur Natur

Trotz dem grundsätzlichen freien Zugang zur Natur sieht der Gesetzgeber zum Schutz und Erhalt von Pflanzen und (Wild-)Tieren – insbesondere für den sensiblen Bereich unterhalb der Waldgrenze im Winter – Einschränkungen für Schneesportler*innen vor. Nebst Einschränkungen direkt aus den hiervor genannten Gesetzesbestimmungen (Art. 14 Abs. 2 WaG und Art. 699 Abs. 1 ZGB), spielen für Schneesportler*innen nebst jener des Natur- und Heimatschutzes besonders die aus der eidgenössischen und kantonalen Jagdgesetzgebung eine grosse praktische Rolle.

1. Eidgenössische Jagdbanngebiete (Wildtierschutzgebiete)

Gemäss Art. 11 Abs. 2 des Bundesgesetzes über die Jagd und den Schutz wildlebender Säugetiere und Vögel vom 20. Juni 1986 (Jagdgesetz, SR 922.0) scheidet der Bundesrat im Einvernehmen mit den Kantonen eidgenössische Jagdbanngebiete aus und erlässt hierzu die Schutzbestimmungen (Art. 11 Abs. 6 Satz 1 JSG). Diese bezwecken einerseits den Schutz und Erhalt von seltenen und bedrohten wildlebenden Säugetieren und Vögeln sowie ihrer Lebensräume. Andererseits geht es um die Erhaltung von gesunden, den örtlichen Verhältnissen angepassten Beständen jagdbarer Arten (Art. 1 der Verordnung über die Eidgenössischen Jagdbanngebiete vom 30. September 1991 [VEJ, SR 922.31]). Zurzeit bestehen schweizweit 42 Jagdbanngebiete, die gemäss Art. 2 VEJ in deren Anhang 1 aufzulisten und in Bundesinventar aufzunehmen sind (Peer, Rz. 15 f.).

In diesen Jagdbanngebieten ist es verboten, ausserhalb von markierten Pisten, Routen und Loipen skizufahren. Zudem sind Hunde – mit Ausnahme der Nutzhunde in der Landwirtschaft – an der Leine zu führen (Art. 5 Abs. 1 lit. c und g VEJ). Widerhandlungen können mit Freiheitsstrafe oder Geldstrafe bzw. mit Busse geahndet werden, wobei auch die fahrlässige Begehung strafbar ist (vgl. Vergehenstatbestand von Art. 17 Abs. 1 lit. f sowie Übertretungstatbestand von Art. 18 Abs. 1 lit. d und e JSG). Für Schneesportler*innen ist der Übertretungstatbestand von praktischer Relevanz, konkret das Verbot Schutzzonen ausserhalb der bezeichneten Routen und Wege zu betreten bzw. zu befahren, ansonsten Ordnungsbussen von CHF 150.00 ausgesprochen werden können (Art. 18 Abs. 1 lit. e und Abs. 3 JSG, Art. 4ter JSV sowie Art. 1 lit. b i.V.m. Anhang 2 der Ordnungsbussenverordnung des Bundes vom 16. Januar 2019 [OBV, SR 314.11]). Die Strafverfolgung obliegt hierbei den Kantonen (Art. 21 Abs. 1 JSG).

2. Kantonale Jagdbanngebiete (Wildtierschutzgebiete) und kantonale / kommunale Wildruhezonen

a. Kantonsebene

Die Kantone können selber weitere Jagdbanngebiete ausscheiden (Art. 11 Abs. 4 JSG). Des Weiteren können die Kantone sogenannte Wildruhezonen ausscheiden und die darin zur Benutzung erlaubten Routen und Wege bezeichnen, soweit es für den ausreichenden Schutz der wildlebenden Säugetiere und Vögel vor Störung durch Freizeitaktivitäten und Tourismus erforderlich ist (Art. 4ter der Verordnung über die Jagd und den Schutz wildlebender Säugetiere und Vögeln vom 29. Februar 1988 [Jagdverordnung, SR 922.01]).

Wildruhezonen sind für Säugetiere und Vögel wichtige Gebiete, in denen die Bedürfnisse der Wildtiere im Vordergrund stehen. Sie dienen gemäss Jagdgesetz der Vermeidung übermässiger Störung als Antwort auf die zunehmende Freizeitnutzung (Art. 7 Abs. 4 des JSG). Wildruhezonen dürfen während bestimmten Jahreszeiten (beispielsweise Winter, Brut- und Setzzeit) oder in Einzelfällen ganzjährig nicht oder nur beschränkt für Freizeitaktivitäten genutzt werden. Hierbei ist eine Unterscheidung zwischen den rechtsverbindlichen und den empfohlenen Wildruhezonen zu treffen. Rechtsverbindliche Wildruhezonen werden über den ordentlichen Gesetzgebungsprozess ausgeschieden und beispielsweise im kantonalen Jagdrecht oder in der kommunalen Zonenplanung kodifiziert. Widerhandlungen gegen rechtsverbindliche Wildruhezonen können strafrechtlich geahndet werden. Demgegenüber sind empfohlene Wildruhezonen solche, die nicht gesetzgeberisch erlassen worden sind. Das verfolgte Ziel besteht hierbei mittels emotionaler Ansprache, die Schneesportler*innen aufzuklären sowie zu sensibilisieren und sie dadurch zur Rücksichtnahme zu bewegen. Mangels gesetzlicher Grundlage sind empfohlene Wildruhezonen weder durchsetzbar noch sanktionierbar. Die Wirksamkeit solcher empfohlenen Wildruhezonen ist daher nach Ansicht des Autors fraglich, zumal die jüngsten Ereignisse in Zusammenhang mit der Corona-Pandemie gezeigt haben, dass die Empfehlung zum freiwilligen Tragen von Atemschutzmasken nur beschränkt Wirkung zu entfalten vermochte.

Es ist anzumerken, dass die Kantone zur Bezeichnung von Wildruhezonen unterschiedliche Terminologien verwenden. Sowohl der Kanton Bern als auch der Kanton Graubünden sprechen in ihren kantonalen Gesetzgebungen ausschliesslich von «Wildschutzgebieten», obschon sie auch «Wildruhezonen» im oben verstandenen Sinn regeln (vgl. für den Kanton Bern: Art. 2 der Verordnung über den Wildtierschutz [WTSchV, BSG 922.63], Kanton Graubünden: Art. 27 Abs. 2 und Art. 28 Kantonales Jagdgesetz, SR 740.000).

b. Gemeindeebene

In gewissen Kantonen wird das Recht, Wildruhezonen auszuscheiden, den Gemeinden übertragen. So erlaubt der Kanton Graubünden betroffenen Gemeinden örtliche und zeitliche Zutrittseinschränkungen, wenn in Wildeinstandsgebieten Störungen das ortsübliche Mass übersteigen und dadurch das Leben sowie Gedeihen des Wildes beeinträchtigt wird (Art. 27 Abs. 2 KJG). Die Gemeinde Pontresina beispielsweise verbietet unter Strafandrohung (Busse von CHF 200.00) in der Zeit vom 15. Dezember bis am 15. April jegliche Schneesportaktivitäten im Wald- und Wildschutzzonen ausserhalb von gekennzeichneten oder markierten Wegen und Pisten/Loipen (Art. 92 Baugesetz und Art. 2n Ordnungsbussenverordnung der Gemeinde Pontresina). Auch im Kanton Bern können die Gemeinden Wildruhezonen erlassen (Art. 2 Abs. 2 lit. e WTSchV) und im Widerhandlungsfall Bussen von CHF 150.00 aussprechen (Art. 1 i.V.m Anhang 1 Abs. 6 Ziff. 29 und 29a der kantonalen Ordnungsbussenverordnung vom 18.09.2022, BSG 324.111).

c. Kasuistik

Gerichtsentscheide sind in diesem Bereich eher dürftig. Dies lässt sich einerseits damit erklären, dass Strafanzeigen, beispielsweise durch Wildhüter*innen, eher selten sind, da fehlbare Schneesportler*innen aus Beweisgründen faktisch in flagranti erwischt werden müssen. Andererseits trägt sicherlich auch der Umstand dazu bei, dass die Widerhandlungen lediglich Übertretungen darstellen.

Das Bundesgericht hat in einem der wenigen Entscheide die Rechtmässigkeit der Bussenauferlegung von CHF 100.00 zulasten eines Schneesportlehrers wegen Befahrens einer Wildruhezone in Laax GR letztlich bestätigt, die durch einen Wildhüter zur Anzeige gebracht wurde (BGer 6B_13/2013 vom 5. Februar 2013, E. 1 bzgl. Anzeige durch Wildhüter, E. 3 bzgl. Begründung und Bestätigung der Busse).

3. Nachttouren

Für die immer beliebter werdenden Touren in der Nacht, insbesondere bei Vollmond, existieren keine spezifische Gesetzesbestimmungen. Vielmehr gelten die allgemeinen, für die Jagdbanngebiete und Wildruhezonen aufgestellten Regeln. Nichtsdestotrotz sollten sich die Schneesportler*innen bewusst sein, dass viele Wildtiere in der Dämmerung und Nacht besonders empfindlich auf Störungen reagieren. Dazu trägt zusätzlich der Umstand bei, dass vielleicht mit Ausnahmen von Vollmondtouren die Schneesportler*innen (notgedrungen) Stirnlampen verwenden.

4. Heliskiing

Das Heliskiing stösst in den Schweizer Alpen nicht zuletzt deshalb auf besonderes Interesse, weil es in unseren Nachbarsländern Frankreich (art. L363-1 du Code de l’environnement) und Deutschland gänzlich verboten und in Österreich einzig im Bundesland Voralberg erlaubt ist.

Zur Beförderung von Schneesportler*innen im schweizerischen Luftraum mittels Luftfahrzeugen ist das Bundesgesetz über die Luftfahrt vom 21. Dezember 1948 (Luftfahrgesetz, LFG SR 748.0) einschlägig. Im Bereich des Heliskiings ist besonders hervorzuheben, dass ausschliesslich auf Gebirgslandeplätzen gelandet werden darf, die durch das Bundesamt für Zivilluftfahrt (BAZL) bezeichnet werden. Als Gebirgslandeplätze gelten vierzig Landestellen ausserhalb von Flugplätzen über 1'100 M.ü.M., die als Aussenlandungen im Gebirge zur Personenbeförderung und zu touristischen Zwecken verwendet werden dürfen (Art. 8 LFG und Art. 2 lit. r i.V.m Art. 54 der Verordnung über die Infrastruktur der Luftfahrt vom 23 November 1994, VIL, SR 748.131.1). Die Liste mit den durch das BAZL zugelassenen Gebirgslandeplätzen sind in der Luftfahrtpublikation veröffentlicht (vgl. «Visual flight rules Manuel Switzerland», Titel 3-3-1).

Im Bereich des Schneesports sind in rechtlicher Hinsicht die rechtswidrigen Hubschrauberlandungen im Gebirge zwecks Heliskiings von praktischer Relevanz. Die Landung ausserhalb von offiziellen Gebirgslandeplätzen stellt einen Übertretungsstraftatbestand dar, der mit Busse bis zu CHF 20'000.00 geahndet werden kann (Art. 91 Abs. 1 lit. a i.V.m. Art. 8 LFG). Zur Strafverfolgung zuständig ist das BAZL nach den Verfahrensvorschriften des Verwaltungsstrafrechtsgesetzes (Art. 98 Abs. 2 LFG). Im Widerhandlungsfall können zudem unabhängig von allfälligen Strafverfahren – wie im Strassenverkehrsrecht – administrative Massnahmen (Bewilligungs- und Ausweisentzug) verfügt werden (Art. 92 ff. LFG).

5. Organisation von Skitourenrennen

Die Durchführung von grossen (sportlichen) Veranstaltungen im Wald und/oder in eidgenössischen Jagdbanngebieten bedürfen einer kantonalen Bewilligung und sind nur zulässig, wenn die Schutzziele dadurch nicht beeinträchtigt werden (Art. 14 Abs. 2 lit. b WaG bzw. Art. 5 Abs. 2 VEJ).

Erst vor kurzem hiess das Kantonsgericht Wallis mit Entscheid vom 31. Oktober 2022 eine durch Umweltschutzverbände erhobene Beschwerde gegen ein durch den Kanton bewilligtes und durch das eidgenössische Jagdbanngebiet «Val Ferret Combe de l’A» führendes Skitourenrennen gut, so dass die Streckenführung durch die Rennorganisatoren abgeändert werden musste (vgl. Medienmitteilung einer der Beschwerdeführerin).

6. Hilfsmittel für Schneesportler*innen

Damit Jagdbanngebiete und Wildruhezonen für Schneesportler*innen erkennbar sind, sieht der Gesetzgeber zweierlei vor (vgl. Art. 7 VEJ und Art. 4ter Jagdverordnung). Zum einen hat das Bundesamt für Landestopografie (Swisstopo) in den Landeskarten mit Schneesportthematik diese Zonen und die darin zur Benutzung erlaubten Routen zu bezeichnen. Diese Schneesportkarten sind im Internet (https://map.geo.admin.ch) bzw. mittels Applikationen (z.B. «White Risk» und «swisstopo») auf Mobiltelefonen abrufbar und bestens geeignete Instrumente für die Phase der Tourenplanung. Die Jagdbanngebiete sowie die rechtsverbindlichen Wildruhezonen sind rot und die empfohlenen Wildruhezonen gelb eingefärbt. Zum anderen bringen die Kantone direkt im Gelände Markierungen dieser Schutzzonen an; dies meist in Form von Tafeln oder auch elastischen Absperrbändern. Daneben bestehen auch kantonale Internetseiten wie beispielsweise wildruhe.gr.ch, welche über bestehende Regelungen und ausgeschiedene Wildruhezonen informieren. Ebenso sind die durch das BAZL zugelassenen Gebirgslandeplätze diesen Landeskarten zu entnehmen.

III. Strafrecht

A. Allgemeines

In der Schweiz existieren in Zusammenhang mit Schneesportunglücken, worunter auch Lawinenunfälle gehören, im Gegensatz zu beispielsweise Italien, wo das Auslösen einer Lawine eine explizite Straftat darstellt (vgl. Art. 426 und Art. 449 Codice Penale), keine spezifischen Straftatbestände. Das RiskG stellt einzig das Anbieten von Schneesportaktivitäten ohne die hierfür nötige Bewilligung unter Strafe (Art. 15 Abs. 1 lit. b RiskG). Damit dient das RiskG in erster Linie als Bewilligungsgesetz der Qualitätssicherung. Die massgebliche Rechtsquelle zur Beurteilung der strafrechtlichen Folgen von Schneesportunglücken ist daher das Schweizerische Strafgesetzbuch (nachfolgend: StGB).

Die Aufgabe der Strafbehörden (Staatsanwaltschaften und Gerichte) besteht bei alpinen Unglücken darin, menschliche, mit Restrisiken behaftete Entscheidungen in rechtlicher Hinsicht zu überprüfen. Damit ist auch gesagt, dass im Falle eines Schneesportunglücks nicht immer eine oder mehrere Personen zur Rechenschaft gezogen werden. Eine strafrechtliche Verurteilung bedarf stets eines Fehlverhaltens. Die grosse Mehrheit von untersuchten Lawinenunfällen enden sodann ohne rechtliche Konsequenzen (vgl. hierfür Harvey/Schweizer, Rechtliche Folgen nach Lawinenunfällen – eine statistische Auswertung, S. 63 ff.).

1. Geltungsbereich des Strafgesetzbuches / Gerichtsstand

Das «freie» Schneesportgelände ist kein rechtsfreier Raum, weil das StGB gestützt auf das Territorialitätsprinzip auf sämtliche in der Schweiz begangenen Delikte (Verbrechen, Vergehen und Übertretungen) Anwendung findet (Art. 3 Abs. 1 und Art. 104 StGB, vgl. hierzu auch Benisowitsch, S. 62, insb. Fn. 6). Für die Anwendbarkeit des StGB und Zuständigkeit Schweizerischer Behörden reicht nach dem Ubiquitätsprinzip gemäss Art. 8 StGB und Art. 31 Abs. 1 StPO, dass der Handlungsort (Ort der Tatausführung oder des pflichtwidrigen Untätigbleibens) oder der Erfolgsort (Ort des Erfolgseintritts) in der Schweiz liegt (vgl. auch BSK StPO-Bartetzko, Art. 31 N 10). Letztere Frage stellt sich gerade im grenznahen Tourengelände, wenn Schneesportler*innen beispielsweise auf Skihochtouren in Grenzgebieten (Region Monte-Rosa, Silvretta, Bernina, Trient) verunglücken oder in multinationalen Skigebieten (Zermatt/Cervinia, Samnaun/Ischgl, Portes du Soleil) Lawinen auslösen. Nicht vom Anwendungsbereich des StGB erfasst sind Minderjährige, dem Jugendstrafrecht unterstehende Personen, sowie dem Militärstrafrecht unterstehende erwachsene Personen (Art. 9 StGB).

2. Eröffnung einer Strafuntersuchung

Schneesportunglücke im «freien» Schneesportgelände führen insbesondere bei Lawinenniedergängen nicht selten zu schwerwiegenden Folgen. Bei Lawinenunglücken lösen Schneesportler*innen in mehr als 90% der Fälle «ihre» (Schneebrett-)Lawine selber aus (Harvey/Rhyner/Schweizer, S. 47), weshalb regelmässig kein Schicksalschlag bzw. höhere Gewalt vorliegt. Wenn hierbei Personen getötet oder schwer verletzt werden, sind die Staatsanwaltschaften aufgrund des gesetzlichen Verfolgungszwangs verpflichtet, eine Strafuntersuchung (ggf. gegen unbekannt) zur Klärung von allenfalls strafbaren Verhaltensweisen zu eröffnen (Art. 7 StPO). Hierfür werden sie regelmässig durch die Polizei informiert (Art. 307 Abs. 1 und Art. 253 StPO). Weil bei Lawinenunglücken mit Personenschaden zu Beginn das Ausmass und allfällige strafrechtlich relevante Verantwortlichkeiten (Fremdverschulden) unklar sind, ist eine rasche Tatbestandsaufnahme durch die Staatsanwaltschaft anzuordnen. Diese ist vorzugsweise durch alpin geschultes Polizeikorps durchzuführen. Ebenso empfiehlt sich im Hinblick auf ein allfälliges Lawinengutachten eine sachverständige Person mit der Befundaufnahme vor Ort zu beauftragen, weil sich die (Schneedecken-)Verhältnisse aufgrund der Witterung (Niederschlag, Wind, Temperaturen, Strahlung) rasch verändern können. Auch ein Augenschein durch die Verfahrensleitung wird empfohlen. Schliesslich sei darauf hingewiesen, dass die Strafverfolgungsbehörden in Rahmen der Strafuntersuchung von Gesetzes wegen, sowohl belastenden als auch entlastenden Umständen nachzugehen haben (Art. 6 StPO).

B. Besonderes

1. Vorbemerkung

Im Bereich des Schneesports sieht man sich in der Praxis hauptsächlich mit aus Schneesportunglücken resultierenden Fahrlässigkeitsdelikten gegen Leib und Leben konfrontiert (vgl. auch Benisowitsch, S. 71). Das Lehrbuchbeispiel, wonach ein Ehepaar zusammen eine Berg-/Skihochtour unternimmt und der eine Ehegatte den anderen mit Tötungsabsicht, d.h. vorsätzlich, vom Grat stösst, dürfte eben gerade überwiegend in Lehrbüchern vorkommen. Die Strafwürdigkeit der fahrlässigen Deliktsbegehung ergibt sich aus der Beeinträchtigung fremder Rechtsgüter, dadurch entstanden, dass die Täterschaft nicht die von ihr verlangte Sorgfalt angewendet hat und daher für den dadurch entstandenen Erfolg einzustehen hat. Die fahrlässige Deliktsbegehung besteht jedoch nur in den gesetzlich vorgesehenen Fällen (vgl. Art. 12 Abs. 1 StGB)

Schneesportler*innen üben ihre Aktivitäten im «freien» Schneesportgelände grundsätzlich eigenverantwortlich und auf eigenes Risiko aus. Daher können sie sich aus strafrechtlicher Sicht grundsätzlich auch straflos selbstgefährden bzw. selbsttöten (vgl. hierzu auch BGE 134 IV 149, E. 4.5). Schneesportler*innen dürfen beispielsweise in freier Entscheidung lawinengefährdete Hänge betreten und befahren, solange sie ausschliesslich sich selber in Gefahr bringen. Die Strafbarkeitsfrage stellt sich primär erst dann, wenn fremde Rechtsgüter tangiert werden und insbesondere bei «geführten» Touren durch namentlich Bergführer*innen, Schneesportlehrer*innen, Tourenleiter*innen, militärische Führer*innen und «faktische» Führer*innen. In derartigen Fällen ist ein Fremdverschulden zu prüfen, denn Führer*innen trifft nebst dem Schädigungsverbot die Pflicht zu aktivem Tun, die Gäste bzw. Teilnehmenden vor alpinen Gefahren zu schützen. Die meisten tödlichen Bergunfälle (Winter und Sommer) verzeichnen private, d.h. nicht organisierte und geführte, Touren. In den Jahren 2018 - 2022 starben in der Schweiz bei Bergunfällen 81% Personen auf privaten Touren (vgl. SAC Bergnotfallstatistik 2022).

2. Das Fahrlässigkeitsdelikt im Allgemeinen

Gemäss Art. 12 Abs. 3 StGB begeht fahrlässig ein Verbrechen oder Vergehen (oder auch eine Übertretung, vgl. Art. 104 StGB), wer die Folge seines Verhaltens aus pflichtwidriger Unvorsichtigkeit nicht bedenkt oder darauf nicht Rücksicht nimmt. Pflichtwidrig ist die Unvorsichtigkeit, wenn der Täter die Vorsicht nicht beachtet, zu der er nach den Umständen und nach seinen persönlichen Verhältnissen verpflichtet ist. Die Fahrlässigkeitshaftung besteht aus nachfolgenden wesentlichen Merkmalen:

- Ungewolltes Bewirken des tatbestandsmässigen Erfolgs;

- Vorhersehbarkeit der zum Erfolg führenden Geschehensabläufe;

- Sorgfaltspflichtverletzung eines Überlebenden;

- Vermeidbarkeit des tatbestandsmässigen Erfolgs.

a. Ungewolltes Bewirken des tatbestandsmässigen Erfolgs

Die Täterschaft muss durch ihre Handlung unvorsätzlich den Eintritt des tatbestandsmässigen Erfolgs (mit-)verursachen, was einen natürlichen – bei Unterlassungsdelikten einen hypothetischen – Kausalzusammenhang zwischen Verhalten und Erfolgseintritt voraussetzt (Donatsch/Godenzi/Tag, S. 347 f.). Diese Frage ist unter Auswertung aller, auch nachträglich, bekannten Tatsachen nach den Grundsätzen der Logik gestützt auf naturwissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse zu beurteilen (Donatsch/Godenzi/Tag, S. 353 f.). Im Bereich von Lawinenunglücken ist hierfür regelmässig auf ein Lawinengutachten durch eine sachverständige Person zurückzugreifen.

Die Tat kann sowohl durch ein Tun als auch durch pflichtwidriges Untätigbleiben begangen werden. Letzteres aber nur, wenn eine Rechtspflicht (sog. Garantenstellung) und die Möglichkeit zur Vornahme der unterlassenen Handlung besteht (Art. 11 Abs. 1 und 3 StGB). Diese Handlungspflicht entsteht auf der Grundlage des Gesetztes, eines Vertrags, einer freiwillig eingegangenen Gefahrengemeinschaft oder der Schaffung einer Gefahr (Art. 11 Abs. 2 StGB). Bei der rechtlichen Beurteilung von Lawinenunglücken wird in der Praxis regelmässig von Unterlassungsdelikten ausgegangen, obschon eigentlich dogmatisch Begehungsdelikte vorliegen würden. Bei einer beispielsweise durch eine(n) Bergführer*in geführten Skitourengruppe besteht die zum Vorwurf gemachte Handlung regelmässig darin, dass die Skitourengruppe pflichtwidrig unvorsichtig in den lawinengefährdeten Hang geführt wurde. Auch der Umstand, dass die Führungsperson es unterlässt, eine Skitour wegen Lawinengefahr abzubrechen, ist kein Anknüpfungspunkt für eine Unterlassungshandlung, sondern einzig die Kehrseite davon, dass sie die Tour fortführt und mithin handelt (Mathys, S. 86 f.). Es wird daher leichthin übersehen, dass in jedem Fahrlässigkeitsvorwurf eine Unterlassung vorliegt, nämlich die Nichtbeachtung einer Sorgfaltspflicht (Praxiskommentar StGB-Trechsel/Fateh-Moghadam, Art. 11 N 6). Daraus kann aber noch nicht auf ein (unechtes) Unterlassungsdelikt geschlossen werden, weil nach dem in Lehre und Rechtsprechung anerkannten Subsidiaritätsprinzip der Vorwurf primär als Handlung zu verstehen ist, solange ein rechtlich kausales Handeln vorliegt (BSK-Niggli/Muskens, Art. 11 N 53; Praxiskommentar StGB-Trechsel/Fateh-Moghadam, Art. 11 N 6).

In Zusammenhang mit der diskutierten Thematik liegt in der Praxis regelmässig ein Führungs- bzw. Garantenverhältnis vor, weshalb die Diskussion betreffend Begehungs- oder Unterlassungsdelikt primär akademischer Natur ist. Praktische Bedeutung erlangt sie einzig für die Staatsanwaltschaften, die je nach Konstellation ihre Anklage anders formulieren muss, um nicht den Anklagegrundsatz zu verletzen.

b. Vorhersehbarkeit

Die wesentlichen zum Erfolg führenden Geschehensabläufe müssen nach der Adäquanzformel, d.h. dem gewöhnlichen Lauf der Dinge und der allgemeinen Lebenserfahrung, für die Täterschaft vorhersehbar sein. Diese Frage ist im Zeitpunkt des Unfallgeschehens (ex-ante) zu beantworten. Bei Lawinenunfällen steht die Frage nach der Vorhersehbarkeit der Lawinengefahr respektive nach der Wahrscheinlichkeit eines Lawinenniederganges im Vordergrund (vgl. zum Ganzen: BGer 6B_601/2016 vom 7. Dezember 2016 E. 1.1 und 1.4.1; BGer 6B_275/2015 vom 22. Juni 2016 E. 3.1 m.w.H.). Der Begriff der Vorhersehbarkeit im stricto sensu ist eine Rechtsfrage und daher durch das Gericht und nicht etwa durch eine sachverständige Person zu beantworten, die sich auf Tatfragen zu beschränken hat, worunter beispielsweise die Frage fällt, wer oder was die Lawine ausgelöst hat (BGE 91 IV 117 E. 1).

c. Sorgfaltspflichtverletzung

Das Kernstück der Fahrlässigkeitshaftung ist das Vorliegen einer Sorgfaltspflichtverletzung, weshalb sie nachstehend einlässlich im Konkreten zu diskutieren sein wird. Eine Sorgfaltspflichtverletzung liegt vor, wenn die Täterschaft zum Zeitpunkt der Tat aufgrund der Umstände sowie ihren Kenntnissen und Fähigkeiten die mit ihrer Handlungsweise bewirkte Gefährdung der Rechtsgüter des Opfers hätte erkennen können und müssen, und wenn sie zugleich die Grenzen des erlaubten Risikos überschritten hat (BGer 6B_410/2015 vom 28. Oktober 2015 E. 1.3.2 m.w.H.).

Der Inhalt dieser Sorgfaltspflicht kann darin bestehen, eine bestimmte Handlung ganz zu unterlassen (strafbare Handlung, gefährliche bzw. sozialinadäquate Handlung, fehlende Fähigkeit zur Beherrschung der Risiken [Übernahmeverschulden]) oder darin, bei der Ausführung einer an sich nicht pflichtwidrigen, mit Risiken verbundenen Handlung das höchstzulässige Risiko nicht zu überschreiten (Donatsch/Godenzi/Tag, S. 355 ff.). Als erlaubtes Risiko kann ein trotz Ergreifen sämtlicher Vorsichtsmassnahmen nicht vermeidbares Restrisiko bezeichnet werden (Frei, Rz 218 und 649). Schneesporttouren und Varianten stellen grundsätzlich mit Restrisiken behaftete sozialadäquate Handlungen dar (siehe Rz. 110, IV.A.). Im Bereich von Touren und Varianten bemisst sich die Grenze zwischen erlaubtem und unerlaubtem Restrisiko insbesondere nach der voraussehbaren Lawinengefahr und ihren möglichen Folgen (BGE 138 IV 124 E. 4.4.5.)

d. Vermeidbarkeit

Für eine Fahrlässigkeitshaftung wird vorausgesetzt, dass der eingetretene Erfolg mit hoher Wahrscheinlichkeit auf das sorgfaltspflichtwidrige Verhalten der Täterschaft zurückzuführen ist (BGE 135 IV 56 E. 5.1). Dabei wird ein hypothetischer Kausalverlauf untersucht und geprüft, ob der Erfolg bei pflichtgemässem Verhalten ausgeblieben wäre (Praxiskommentar StGB-Trechsel/Fateh-Moghadam, Art. 12 N 39). Sofern der Verletzungserfolg auch bei sorgfaltsgemässem Verhalten eingetreten wäre, scheidet Fahrlässigkeit infolge fehlendem Pflichtwidrigkeitszusammenhang aus. Diese Frage erfolgt – im Gegensatz zu jener der Sorgfaltspflichtverletzung – unter einer ex-post-Betrachtung, womit sämtliche, auch nachträgliche, Erkenntnisse zu berücksichtigen sind. (Donatsch/Godenzi/Tag, S. 381).

C. Die Sorgfaltspflichtverletzung im Besonderen

1. Sorgfaltspflichten von Bergführer*innen und Schneesportlehrer*innen

Die Sorgfaltspflichten der Bergführer*innen und Schneesportlehrer*innen sind explizit gesetzlich normiert, woraus sich – nebst einer meist vertraglichen – auch eine gesetzliche Garantenpflicht ergibt. Art. 2 Abs. 1 RiskG sieht vor, dass, wer eine diesem Gesetz unterstellte Aktivität anbietet, die Massnahmen treffen muss, die nach der Erfahrung erforderlich, nach dem Stand der Technik möglich und nach den gegebenen Verhältnissen angemessen sind, damit Leben und Gesundheit der Teilnehmenden nicht gefährdet werden. Hierzu gehört gemäss Abs. 2 insbesondere die:

- Aufklärung der Kundschaft über die besonderen mit der Ausübung der gewählten Aktivität verbundenen Gefahren;

- Überprüfung des Leistungsvermögens der Kundschaft für die gewählte Aktivität;

- Überprüfung des Materials auf Zustand und Mängelfreiheit;

- Überprüfung der Eignung der Wetter- und Schneebedingungen;

- Sicherstellung von ausreichend qualifiziertem Personal;

- Einsatz von genügend Personal in Abhängigkeit von der Schwierigkeit und Gefahr der Aktivität;

- Rücksichtnahme auf die Umwelt (Tiere und Pflanzen).

Im Bereich von Schneesporttouren und Varianten kommt der Beurteilung der «Eignung der Wetter- und Schneebedingungen» und mitunter der Lawinengefahr grösste Bedeutung zu, zumal zweidrittel der Todesfälle auf Lawinenniedergänge zurückzuführen sind. Doch weder das Gesetz noch die dazugehörige Verordnung erläutern dies näher. Zu deren Konkretisierung sind daher allgemein anerkannte Verhaltensregeln von privaten oder halböffentlichen Verbänden heranzuziehen, auch wenn diese keine Rechtsnormen darstellen (BGer 6B_92/2009 vom 18.06.2009 E. 3.3.1 m.w.H.; BGer 6B_727/2020 vom 28. Oktober 2021 E. 2.3.3). Für die rein alpinistischen Sorgfaltspflichten, wie sie auf Skihochtouren typischerweise mit Kletterstellen vorkommen, wird auf den Bergsportkommentar «Alpinisme» verwiesen (Kuonen, passim).

Zur Beurteilung der Wetter- und Schneebedingungen gehört bei Schneesporttouren und Varianten im Besonderen die Lawinenrisikobeurteilung dazu. In der Schweiz haben die massgebenden Berufs- und Sportverbände (Bergführerverband, Schneesportlehrerverband, Swiss Ski, Seilbahnen Schweiz, diverse Rettungsorganisationen) sowie der Bund und bundesnahe Betriebe (SLF, Bundesamt für Sport, Armee, SUVA, Beratungsstelle für Unfallverhütung BFU) sich im Sinne einer «unité de doctrine» auf Standards geeinigt und hierzu das «Kernausbildungsteam Lawinenprävention Schneesport» (KAT) gegründet. Das vom KAT herausgegebene Merkblatt «Achtung Lawinen!», welches höchst komprimiert Beurteilungs- und Entscheidungshilfen für das Lawinenrisikomanagement beschreibt, hat ihren Ursprung in dem durch den Bergführer Werner Munter kreierten Beurteilungssystem nach der (Filter-)Methode 3x3 (Werner Munter, 3x3 Lawinen, Risikomanagement im Wintersport). Dieses regelmässig überarbeitete Merkblatt konsolidiert den neusten Stand von Forschung und Praxis und bedarf zwingend eines Rückgriffes auf die Fachliteratur, weil es nicht selbsterklärend ist und Vorkenntnisse bedarf. Der Kommentar zur Risikoaktivitätenverordnung als Auslegungshilfe der gesetzlichen Sorgfaltspflichten verweist sodann auch explizit auf dieses Merkblatt (Kommentar zu Art. 6 RiskV).

a. Lawinenrisikobeurteilung lege artis

Die 3x3 Filtermethode erlaubt eine systematische Vorgehensweise, um in drei aufeinanderfolgenden Phasen der Planung, Evaluation vor Ort und der Einzelhangbeurteilung eine risikobewusste, vertretbare Entscheidung zu treffen.

Planung

Ausgangspunkt der Lawinenrisikobeurteilung ist die vorgängige Planung der Schneesporttour oder Variante, in der die Faktoren Verhältnisse, Gelände und Mensch beurteilt werden. Ziel ist es, ein Tourenziel zu definieren, das zur aktuellen Wetter- und Lawinensituation sowie den Bedürfnissen und Fähigkeiten aller Beteiligten passt. Hierzu ist gemäss konstanter Praxis des Bundesgerichts zwingend das im Winter täglich erscheinende Lawinenbulletin des SLF (samt dazugehöriger Interpretationshilfe) zu konsultieren (BGer 6B_275/2015 vom 22. Juni 2016 E. 3.2 m.w.H.; BGer 6B_92/2009 vom 18. Juni 2009 E. 3.3.1 m.w.H.; abrufbar unter: SLF Startseite - SLF). Dieses um 17:00 Uhr und tags darauf um 08:00 Uhr erscheinende nationale Lawinenbulletin beschreibt die zu erwartende Lawinensituation für eine Region. Von Bedeutung ist, dass es sich hierbei «lediglich» um eine Prognose handelt, was das Bundesgericht auch richtig erkennt, wenn es ausführt, dass letztlich stets die lokalen Gegebenheiten zu beurteilen sind (BGer 6B_403/2016 vom 28. November 2017 E. 3.1 m.w.H.).

Die Lawinengefahr wird einer der fünf europäischen Gefahrenstufen (Stufe 1 – gering; Stufe 2 – mässig; Stufe 3 – erheblich; Stufe 4 – gross; Stufe 5 – sehr gross) zugeordnet. Mit der Wintersaison 2022/2023 wurden ab der Lawinengefahrenstufe mässig (Gefahrenstufe 2) Zwischenstufen eingeführt, die Auskunft darüber geben, ob die Gefahr eher im unteren Bereich (-), etwa in der Mitte (=) oder eher im oberen Bereich (+) innerhalb der Gefahrenstufe liegt. Dies gilt jedoch ausschliesslich für Trockenlawinen. Die Lawinengefahr umschreibt die Wahrscheinlichkeit und Grösse von Lawinen in einer Region und nicht die Auslösewahrscheinlichkeit. Die Lawinengefahr steigt sodann von Stufe zu Stufe nicht linear, sondern überproportional. Je höher die Lawinengefahrenstufe ist, desto häufiger sind die Stellen mit sehr schwacher Schneedeckenstabilität, wo eine Lawinenauslösung möglich ist, und desto häufiger sowie tendenziell grösser sind die zu erwartenden Lawinen. Des Weiteren bezeichnet das Lawinenbulletin die Gefahrenstellen (Höhenlage und Hangexposition), in denen die Lawinengefahr hauptsächlich vorherrscht, so dass im Sinne einer Faustregel in den nicht explizit bezeichneten Gefahrenstellen grundsätzlich eine Gefahrenstufe weniger angenommen werden kann. Dasselbe gilt für das Variantengelände, das aufgrund der Nähe zur Bergbahninfrastruktur in der Regel häufiger befahren und teilweise auch durch die Bergbahnbetreiberinnen gesichert wird. Dadurch weist dieses Schneesportgelände regelmässig einen günstigeren Schneedeckenaufbau auf, weshalb oft eine Gefahrenstufe weniger angenommen werden kann. Schliesslich weist das Lawinenbulletin auf eines der fünf zu erwartenden Lawinenproblemen hin (Neuschnee, Triebschnee [Wind], Altschnee [schwache Schneedecke], Nassschnee [Wasser], Gleitschnee), so dass je nach Problem unterschiedliche Massnahmen und Verhaltensweisen zu ergreifen sind. Schliesslich umfasst es allgemeine Informationen zum Schneedeckenaufbau und zum Wetter (vgl. zum Ganzen: Harvey/Rhyner/Schweizer).

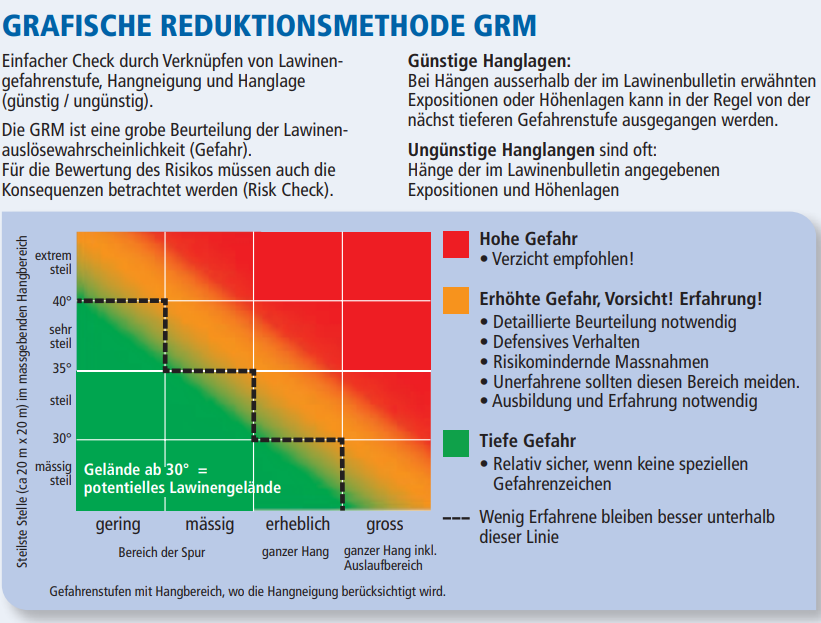

Ebenfalls sind in der Planungsphase anhand von Landeskarten und Hangneigungskarten –Papierkarten oder heutzutage vielfach mit Digitalkarten von Swiss Topo (gratis abrufbar unter map.geo.admin.ch) – sogenannte Schlüsselstellen zu identifizieren. Anhand einer Reduktionsmethode, wie beispielsweise der weit verbreiteten und sowohl in der Schneesportlehrerausbildung als auch in den SAC-Tourenleiterkursen verwendeten Graphischen Reduktionsmethode (GRM), ist eine erste Lawinenrisikobeurteilung vorzunehmen.

Quelle: Merkblatt «Achtung Lawinen!»

Quelle: Merkblatt «Achtung Lawinen!»

Mit dieser GRM lässt sich anhand der beiden Parameter Lawinengefahrenstufe/Hangsteilheit die Gefahr einer Lawinenauslösung an einem bestimmten Hang grob abschätzen. Es ist wichtig zu wissen, dass Schneebrettlawinen erst ab einer Hangneigung von 30° entstehen (Harvey/Rhyner/Schweizer, S. 49). Die GRM beinhaltet die elementare Reduktionsmethode von Werner Munter mit klar definierten Grenzwerten, wonach bei Gefahrenstufe mässig (Stufe 2) Hänge unter 40°, bei Gefahrenstufe erheblich (Stufe 3) Hänge unter 35° und bei Gefahrenstufe gross (Stufe 4) Hänge unter 30° begangen werden sollten. Sofern man diese Limiten berücksichtigt, bewegt man sich gemäss GRM stets maximal im orangenen Bereich. Nebst der GRM wird insbesondere in der Bergführerausbildung oft die Professionelle Reduktionsmethode (PRM) von Werner Munter verwendet. Aufgrund neuster wissenschaftlicher Erkenntnisse dürfte die PRM aber an Bedeutung verlieren, weil diese auf einer Verdoppelung der Lawinengefahr von einer Gefahrenstufe zur nächsten basiert, obschon Studien nun gezeigt haben, dass die Lawinengefahr von einer Gefahrenstufe zur nächsten um das Vierfache ansteigt (Winkler et. al., S. 1 ff.). Schliesslich darf auch die relativ junge quantitative Reduktionsmethode (QRM) nicht unerwähnt bleiben. Bei dieser auf der "künstlichen Intelligenz" basierenden Reduktionsmethode errechnet ein Algorithmus anhand von Daten (digitale Höhenmodelle, aktuelles Lawinenbulletin) zwei Mal täglich das Lawinenrisiko für jeden Punkt einer Vielzahl von Schneesporttouren (vgl. hierzu Skitourenguru.ch).

Evaluation vor Ort

In einem zweiten Schritt ist vor Ort im Gelände/Skigebiet zu beurteilen, ob die geplanten bzw. erwartenden Faktoren Verhältnisse, Gelände und Mensch mit den tatsächlichen übereinstimmen. Ziel ist es zu entscheiden, ob die geplante Tour/Variante durchgeführt werden kann oder von Beginn weg bzw. im Verlauf der Tour auf ein Alternativziel auszuweichen oder gar der Rücktritt anzutreten ist.

Ein wesentlicher Faktor hierfür ist die Überprüfung, ob die regional prognostizierte Lawinengefahr den lokalen Gegebenheiten entspricht, wofür aktiv Beobachtungen im Schneesportgelände anzustellen sind (insbesondere Neuschneemenge, Alarmzeichen wie frische und spontane Lawinenabgänge, Windeinfluss). Wer sich ins «freie» Schneesportgelände begibt, muss – unabhängig von der Lawinengefahrenstufe – die Lawinennotfallausrüstung mitführen. Entsprechend ist spätestens zu diesem Zeitpunkt auch das Material der Teilnehmenden zu prüfen und eine Kontrolle des Lawinenverschüttetensuchgeräts (LVS) vorzunehmen. Gemäss herrschender Doktrin besteht die absolut zwingende Notfallausrüstung aus dem (sendenden) LVS-Gerät, einer Lawinenschaufel und Sonde (Harvey/Rhyner/Schweizer, S. 26 f., 300 f.; Winkler/Brehm/Haltmeier, S. 66 f.). Der Lawinenairbag ist gemäss Konsens in den Fachkreisen (nach wie vor) nicht Bestandteil der obligatorischen Sicherheitsausrüstung. Weil Berufspersonen verpflichtet sind, alle nach dem Stand der Technik möglichen und zumutbaren Mittel einzusetzen, sind nach hier vertretener Auffassung nunmehr zwingend Drei-Antennen-LVS zu verwenden. Es ist bekannt, dass bei Totalverschüttungen (Kopf im Schnee) die häufigste Todesursache das Ersticken ist, da oft keine oder nur eine kleine Atemhöhle besteht. Statistisch gesehen überleben rund 90% der Verschütteten, die nicht bereits aufgrund vorgängiger Traumaverletzungen im Rahmen des Mitrisses versterben (was bei jedem Dritten der Fall ist), wenn sie in den ersten 15 Minuten geborgen werden. Danach sinkt die Überlebenschance rasant (vgl. Studie von Procter et al., S. 173–176). Die rasche Kameradenrettung ist für das Überleben daher entscheidend, weshalb hierfür ausschliesslich LVS-Geräte der neusten Generation, d.h. mit drei Antennen, einzusetzen sind (vgl. hierzu auch Winkler/Brehm/Haltmeier, S. 248 f.). In diesem Zusammenhang sei erwähnt, dass die Recco-Reflektoren, die in Wintersportbekleidungen und nunmehr auch in Skischuhen eingebaut werden, kein Ersatz für LVS-Geräte darstellen. Die Suche mittels Recco-Geräts erfolgt ausschliesslich durch die professionelle Rettung, die im Gegensatz zur Kameradenrettung, regelmässig zu spät auf dem Schadensplatz eintrifft. Schliesslich ist mangels vollständiger Mobilfunknetzabdeckung im Gebirge für jene Regionen, in denen bekanntermassen kein Mobilfunknetz besteht, gemäss hier vertretener Auffassung zwingend ein über das Mobiltelefon hinausgehendes Kommunikationsmittel (Funk- oder Satellitengerät) mitzuführen, da gerade bei Lawinenverschüttungen stets Lebensgefahr besteht und parallel zur Kameradenrettung die professionellen Rettungskräfte so rasch als möglich zu alarmieren sind (Winkler/Brehm/Haltmeier, S.66 f., 247 f., 271). Als Hilfsmittel können die Netzabdeckungskarten der drei grossen schweizerischen Telekommunikationsanbieterinnen im Internet konsultiert werden (vgl. Swisscom, Salt, Sunrise).

Einzelhangbeurteilung

In einem letzten und entscheidenden Schritt ist der Einzelhang – regelmässig die identifizierte(n) Schlüsselstelle(n) – abschliessend zu beurteilen und zu entscheiden, ob dieser (vernünftigerweise) begangen werden kann oder nicht und falls ja, gegebenenfalls mit welchen risikominimierenden Massnahmen (Entlastungsabstände, Einzelbegehung, Spuranlage in Auf-und Abfahrt). Hierzu sind wiederum die Faktoren Verhältnisse, Gelände und Mensch miteinzubeziehen. Bei der Beurteilung des Einzelhanges stehen vor allem die Schnee- und Lawinenverhältnisse im Hang und die spezifischen Geländeeigenschaften (Grösse, effektive Steilheit, Geländeform, Geländefallen) im Vordergrund. In diesem Stadium müssen auch zwingend die Konsequenzen eines Lawinenniederganges (Absturz, Totalverschüttung, Traumaverletzung während Mitrisses, etc.) berücksichtigt werden. Schliesslich kommt auch dem Faktor Mensch grösste Bedeutung zu (Können, körperliche und psychische Verfassung, «Gehorsam» bzw. Disziplin).

b. Sorgfaltsmassstab

Das Gesetz selber legt das höchstzulässige Risiko nicht dar, weil im Strafrecht selbst die individuell-konkreten Sorgfaltspflichten nicht umschrieben sind (Donatsch/Godenzi/Tag, S. 361). Nach dem individuellen Sorgfaltsmassstab von Art. 12 Abs. 3 StGB ist das Risiko, welches mit riskanten Tätigkeiten maximal verbunden sein darf unter Berücksichtigung der konkreten Umstände des Falles sowie den persönlichen Verhältnissen des Handelnden zu bestimmen, wozu namentlich die berufliche Ausbildung und Erfahrung, geistige Anlagen und Bildung gehört (BGer 6B_727/2020 vom 28. Oktober 2021 E. 2.3.3 in fine; Praxiskommentar StGB-Trechsel/Fateh-Moghadam, Art. 12 N 35). Die Frage nach dem zulässigen bzw. unzulässigen Risiko stellt im Ergebnis daher eine Frage der Würdigung dar. Es ist hervorzuheben, dass mit der ersatzlosen Streichung von Art. 7 Abs. 1 lit. c aRiskV per 1. Mai 2019, der für Schneesportlehrer*innen vorsah, dass die Lawinenrisikobeurteilung für sie höchstens ein geringes Lawinenrisiko ergeben durfte (nicht zu verwechseln mit Lawinengefahrenstufe «gering»), sich die Lawinenrisikobeurteilung für Schneesportler*innen nunmehr nach den allgemeinen Schranken des «erlaubten» Risikos bemisst.

Aufgrund ihres besonderen Fach- und Erfahrungswissens kommen den Schneesportlehrer*innen, vor allem aber den Bergführer*innen ein erhöhter Sorgfaltsmassstab zu (BGer 6B_275/2015 vom 22. Juni 2016 E. 3.2 m.w.H.; Benisowitsch, S. 142 und 149; Frei, Rz. 147; Gerber, S. 149, 155 ff.). Auf der anderen Seite ist ihnen aber bei der Entscheidfindung ein grösserer Ermessensspielraum zuzugestehen, als jenen Personen, denen diese Fähigkeiten und Fachkenntnisse abgehen (BGE 97 IV 169, E. 2). So sind Bergführer*innen beispielsweise befähigt, im Gelände komplett eigenständig ein Lawinenbulletin zu erstellen (vgl. hierfür beispielsweise «Nivocheck 2.0» des Schweizerischen Bergführerverbands, Winkler/Brehm/Haltmeier, S. 118 ff.). Die Lawinenkunde und die damit einhergehende Gefahrenbeurteilung ist keine exakte Wissenschaft und mit grossen Unsicherheiten verbunden. Den Bergführer*innen und Schneesportlehrer*innen stehen, ähnlich der Ärzteschaft in der Heilkunde, verschiedene Beurteilung- und Entscheidungshilfen zur Lawinenrisikobeurteilung und -minimierung zur Verfügung. Schneesportlehrer*innen und Bergführer*innen haben die nach den Umständen gebotene sowie zumutbare Sorgfalt zu beachten und stehen nicht für sportimmanente Risiken ein. In Anlehnung an die bundesgerichtliche Rechtsprechung zur ärztlichen Sorgfaltspflicht begehen Schneesportlehrer*innen und Bergführer*innen erst dann eine Sorgfaltspflichtverletzung, wenn ihr Vorgehen nach dem allgemeinen fachlichen Wissenstand als nicht mehr vertretbar erachtet werden kann und den objektivierten Anforderungen der «alpinen Kunst» nicht genügen (BGer 6B_727/2020 vom 28. Oktober 2021 E. 2.3.4).

Zur Beurteilung des rechtlich höchstzulässigen Risikos stellen die Reduktionsmethoden, insbesondere die GRM, geeignete Beurteilungsmittel dar. Der Aufenthalt in der orangenen bzw. gar roten Zone gemäss GRM bedeutet aber noch nicht per se ein «unerlaubtes» Risiko. Es bedarf stets einer Beurteilung des Einzelfalles unter Berücksichtigung sämtlicher konkreter Umstände. Während bei lawinenkundigen und erfahrenen Schneesportler*innen der Aufenthalt im orangenen bzw. gar roten Bereich gemäss Reduktionsmethode im Einzelfall noch als erlaubtes Risiko angesehen werden kann, dürften sich unerfahrene Schneesportler*innen ohne Weiteres im Bereich des «unerlaubten» Risikos befinden.

2. Sorgfaltspflichten von Tourenleiter*innen

Die Sorgfaltspflichten von ehrenamtlichen Tourenleiter*innen sind nicht spezifisch gesetzlich normiert, zumal das RiskG explizit nicht anwendbar ist (Art. 2 Abs. 2 RiskV). Dies ändert aber nichts daran, dass auch Tourenleiter*innen die wesentlichen Sorgfaltspflichten jederzeit einzuhalten haben, insbesondere soweit es um elementare Sicherheitsstandards geht (vgl. auch Benisowitsch, S. 176). Die Sorgfaltspflichten erfolgen wie bei den Berufspersonen durch Rückgriff auf allgemein anerkannte Verhaltensregeln von privaten oder halböffentlichen Verbänden. Die SAC Tourenleiter*innen sowie J+S Leiter*innen werden im Bereich Winter insbesondere auf der Grundlage des SAC-Lehrbuchs «Bergsport Winter» und dem Merkblatt «Achtung Lawinen!» ausgebildet, weshalb die Lawinenrisikobeurteilung nach denselben Grundsätzen wie für Bergführer*innen und Schneesportlehrer*innen zu erfolgen hat und entsprechend darauf verwiesen werden kann (vgl. Rz. 63, III.C.1.a hiervor). Im Übrigen ergeben sich die Sorgfaltspflichten für SAC Tourenleiter*innen auch aus dem SAC-Leitfaden «Rechtliche Stellung von Tourenleiter*innen des SAC», welcher aktuell überarbeitet wird. Zu beachten ist aufgrund des individuellen Sorgfaltsmassstab, dass dieser für Tourenleiter*innen und J+S Leiter*innen regelmässig weniger hoch anzulegen ist als bei Bergführer*innen und Schneesportlehrer*innen (vgl. Gerber, S. 173).

Tourenleiter*innen und J+S Leiter*innen müssen jedoch zwingend beachten, dass sie die Fähigkeiten besitzen, die mit der Übernahme der Tätigkeit verbundenen Gefahren zu erkennen, ansonsten sie sich der Übernahmefahrlässigkeit schuldig machen (Donatsch/Godenzi/Tag, S. 358 f.). Diese Minimalfähigkeiten zur Risikoeinschätzung im Schneesportgelände werden im Rahmen des SAC und J+S dahingehend sichergestellt, als dass einerseits die Leiter*innen Ausbildungskurse zu durchlaufen haben und andererseits ihre Touren durch interne Instanzen überprüft und bewilligt werden müssen (vgl. Rz. 21, I.B.2a. hiervor).

3. Sorgfaltspflichten von «faktischen» Führern*innen

Das Bundesgericht hat erwogen, dass die Verantwortung eines faktischen Führers für die Sicherheit der ihm anvertrauten Gruppe jener von Berufspersonen nicht nachsteht (BGE 83 IV 9 E. 1, vgl. auch Gerber, S. 181 f.). Es kann daher auf die entsprechenden Sorgfaltspflichten der Bergführer*innen und Schneesportlehrer*innen verwiesen werden (vgl. Rz. 60, III.C.1. hiervor). Dem individuellen Sorgfaltsmassstab ist auch bei der faktischen Führerschaft stets Rechnung zu tragen, weshalb dieser regelmässig weniger hoch anzulegen sein dürfte als bei Berufspersonen, sofern es sich effektiv nicht um Berufspersonen handelt, die im privaten Rahmen unterwegs sind. Es gilt auch hier, dass auf die Führungsrolle verzichtet werden muss, wenn keine Gewähr für die erforderliche Sicherheit geleistet werden kann, ansonsten die «faktische» Führerschaft ein Übernahmeverschulden begeht.

4. Sorgfaltspflichten von militärischen Führern*innen

Für militärische Bergführer gelten nebst den allgemeinen Sorgfaltspflichten ihres Berufsstandes (vgl. Rz. 63, III.C.1.a hiervor) auch spezifische militärische Bestimmungen (Reglemente, Dienstbefehle, etc.). Die Gebirgsspezialisten ihrerseits werden auf der Grundlage ziviler Fachbücher, insbesondere dem SAC-Lehrbuch «Bergsport Winter» und dem Merkblatt «Achtung Lawinen!» ausgebildet. Der Sorgfaltsmassstab entspricht in etwa jenem der SAC-Tourenleiter*innen der Stufe Winter 2, weshalb auf die entsprechenden Ausführungen verwiesen werden kann (vgl. Ziff. 3 b. hiervor).

D. Die Straftatbestände im Einzelnen

1. Fahrlässige Tötung / Fahrlässige schwere bzw. einfache Körperverletzung

Der fahrlässigen Tötung gemäss Art. 117 StGB macht sich strafbar, wer fahrlässig den Tod eines Menschen verursacht. Der fahrlässigen schweren oder einfachen Körperverletzung gemäss Art. 125 StGB macht sich seinerseits strafbar, wer einen Menschen fahrlässig am Körper oder an der Gesundheit schädigt.

Ein Schuldspruch setzt somit voraus, dass die Täterschaft den Tod bzw. die Körperverletzung eines Menschen durch Verletzung einer Sorgfaltspflicht verursacht hat. Die rechtliche Unterscheidung zwischen schwerer und einfacher Körperverletzung ist nicht immer einfach, weshalb unter Umständen auf rechtsmedizinische Gutachten zurückzugreifen ist. Die Unterscheidung ist nicht nur für die Bestimmung der Strafe im Falle eines Schuldspruches von Bedeutung, sondern auch aus prozessualen Gründen. Während die fahrlässige schwere Körperverletzung ein Offizialdelikt darstellt, handelt es sich bei der fahrlässigen einfachen Körperverletzung um ein Antragsdelikt, das nur auf Wunsch der geschädigten Person verfolgt wird (vgl. Art. 30 f. StGB). Letztere Unterscheidung kennt das Militärstrafgesetzbuch jedoch nicht, so dass sämtliche Körperverletzungen von Amtes wegen zu verfolgen sind (Art. 124 MStG).

a. Lawine Roc d'Orzival auf Variante – Fahrlässige Tötung Bergführer (Schuldspruch)

Das Bundesgericht bestätigte den vorinstanzlichen Schuldspruch wegen fahrlässiger Tötung eines Bergführers (BGer 6B_275/2015 vom 22. Juni 2016). Dieser unternahm bei schönem und schwachwindigem Wetter und der Lawinengefahrenstufe erheblich (Stufe 3) in Grimentz VS eine Variantenabfahrt mit einer fünfköpfigen Skigruppe. Drei Tage zuvor hatte es zuletzt rund 50 cm Neuschnee gegeben. Bevor die Gruppe einen Nordosthang von über 40° unterhalb eines Grates rund 20 m traversieren sollte instruierte der Bergführer seine Gäste, mahnte diese zur Vorsicht und ordnete ein Einzelfahren an. Er ordnete jedoch nicht an, zwingend in seiner Spur zu fahren. Nachdem der Bergführer und drei Gäste die Traverse passiert hatten, geriet der zweitletzte Gast auf der Traverse in eine Lawine und konnte trotz rascher Kameradenrettung nur noch tot geborgen werden.

Das Gericht bejahte eine Sorgfaltspflichtverletzung des Bergführers, weil er im Unglückshang nicht die sicherste Route gewählt hatte und zur Beurteilung der Lawinengefahr im Einzelhang sich lediglich auf eine aussageschwache Schneedeckenuntersuchung mittels Skistock und eigenen Sprüngen verlassen hatte. Er hätte ohne Weiteres dem (sicheren) Grat folgen können, anstatt abzusteigen und den Unglückshang zu traversieren. Dass die Schneedecke zuvor bei vier Skifahrern gehalten hatte, sei nicht von Bedeutung. Eine Unterbrechung des Kausalzusammenhangs liege zudem nicht vor, weil der Verstorbene sich korrekt verhalten habe. Selbst das Befahren der Spur hätte gemäss Gutachten die Lawine auslösen können, so dass es nicht darauf ankomme, ob der Verstorbene den Unglückshang letztlich in der Spur oder wenige Meter darunter traversiert habe. In dem der Bergführer trotz Vorhersehbarkeit einer Lawinenauslösung und Möglichkeit einer Alternativroute den Unglückshang befuhr, hat er das erlaubte Risiko überschritten und damit eine Sorgfaltspflichtverletzung begangen.

b. Gletscherspaltensturz Vadret da Roseg auf Skihochtour – Fahrlässige Tötung Bergführer (Schuldspruch)

Zwei Bergführer unternahmen mit ihren Gästen unangeseilt eine Skihochtour auf den Piz Glüschaint GR, als im Aufstieg auf dem Vadret da Roseg bei einem Gast die Schneebrücke nachgab, wodurch dieser 30 m in eine Gletscherspalte zu Tode stürzte. Das Gericht bestätigte den vorinstanzlichen Schuldspruch der beiden Bergführer wegen fahrlässiger Tötung. Sie hätten eine Sorgfaltspflichtverletzung begangen, indem sie auf dem stark zerklüfteten und schneebedeckten Gletscher auf das Anseilen verzichteten (Urteil des Kantonsgerichts Graubünden vom 13. September 1995, PKG 1995 Nr. 29, E.2, S. 109 ff., dessen Nichtigkeitsbeschwerde das Bundesgericht in BGer 6S.194/1996 vom 7. Juni 1996 [nicht publiziert] abgewiesen hat).

c. Lawine S-charl auf Skitour – Fahrlässige Tötung Bergführer (Schuldspruch)

Das Bundesgericht bestätigte den vorinstanzlichen Schuldspruch wegen fahrlässiger Tötung eines Bergführers (BGE 118 IV 130). Dieser unternahm mit einer siebenköpfigen Skitourengruppe bei Lawinengefahrenstufe mässig (Stufe 2) eine Skitour auf den Mot San Lorenzo (Lorenziberg) GR durch das Valbella, wozu die Gruppe in geschlossener Formation hochstieg. Als der Nordwesthang steiler wurde, ordnete der Bergführer auf einem kleinen Zwischenboden einen Marschhalt an, um alleine rund 20 m weiter aufzusteigen, um die Festigkeit der Schneedecke zu überprüfen. Hierbei löste sich oberhalb von ihm eine Lawine in einem 38° steilen Couloir, welche die gesamte Gruppe verschüttete. Während es dem Bergführer und einem Gast gelang, sich selber aus den Schneemassen zu befreien, verstarben die übrigen sechs Personen trotz rasch eingeleiteter Kameradenrettung.

Das Bundesgericht sah die Sorgfaltspflichtverletzung des Bergführers darin, dass er den deutlich über 30° steilen Hang ohne Anordnung von Entlastungs-/Sicherheitsabständen mit seinen Gästen beging und die Spur nicht optimal anlegte. Das Gerichtsgutachten beurteilte die Lawinengefahr im Unglückshang als erheblich (Stufe 3), was für den Bergführer aber nicht erkennbar gewesen sei. Zudem hätte auch die pflichtgemässe Anordnung von Entlastungs-/Sicherheitsabständen den Lawinenniedergang nicht verhindert. Hingegen wären mit einer solchen Anordnung höchstwahrscheinlich nicht sämtliche Gruppenmitglieder verschüttet worden. Das Gericht erwog, dass der Bergführer nicht für die Auslösung der Lawine die strafrechtliche Verantwortung trägt, sondern für die unterlassene Anordnung von Entlastungs-/Sicherheitsabständen und dass bei einer optimaleren Spuranlage nicht gleichviele Gäste verstorben wären.

Diesem Urteil kann gemäss der hier vertretenen Auffassung nicht gefolgt werden und die Begründung geht in rechtlicher Hinsicht fehl. Die Lawine war für den Bergführer weder vorhersehbar noch hätte die Anordnung von Entlastungs-/Sicherheitsabständen den Lawinenniedergang verhindert, weshalb ihm keine Sorgfaltspflichtverletzung vorgeworfen werden kann bzw. ein Pflichtwidrigkeitszusammenhang fehlt. Der Begründung des Bundesgerichts folgend, müssten unabhängig von der Lawinengefahr, d.h. auch bei der Lawinengefahrenstufe gering (Stufe 1), zwecks Schadensverminderung stets Entlastungs-/Sicherheitsabstände angeordnet werden.

d. Lawine Davos (Meierhofer-Tälli) auf Variante – Fahrlässige Tötung Freerider (Schuldspruch)

Das Bundesgericht bestätigte den vorinstanzlichen Schuldspruch eines Schneesportlers aus einer vierköpfigen Freerider-Gruppe wegen fahrlässiger Tötung dreier Personen (BGer 6P_163/2004 bzw. 6S.432/2004 vom 3. Mai 2005).