Bibliography

Bütler, Michael, Zur Haftung von Werkeigentümern und Tierhaltern bei Unfällen auf Wanderwegen, Sicherheit&Recht 2/2009, S. 106 ff; Erni, Franz, Unfall am Berg: wer wagt, verliert!, in: Klett, Barbara (Hrsg.), Haftung am Berg, 2013, S. 15 ff.; Galli, Bernhard, Haftungsprobleme bei alpinen Tourengemeinschaften, Frankfurt a.M. 1995; Hogrefe, Juliane, Mountainbiken, in: Anne Mirjam Schneuwly/Rahel Müller (Hrsg.), Bergsportkommentar ; Hungergühler, Francine, Klettern (inkl. Klettersteige), in: Anne Mirjam Schneuwly/Rahel Müller (Hrsg.), Bergsportkommentar ; Kessler, Martin A., in: Widmer Lüchinger, Corinne/Oser, David (Hrsg.), Basler Kommentar zum Obligationenrecht, Bd. I, 7. Aufl., 2020; Müller, Rahel, Haftungsfragen am Berg, Diss. Bern 2016 (zit. Müller, Haftungsfragen); Müller, Rahel, Die neue Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung – was erwartet uns per 1. Januar 2014?, Sicherheit&Recht 2/2013, S. 94 ff. (zit. Müller, Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung); Niggli, Marcel Alexander/Muskens, Louis Frédéric, in: Niggli, Marcel Alexander/Wiprächtiger, Hans (Hrsg.), Basler Kommentar zum StGB, 4. Aufl 2018, Art. 11 StGB; Nosetti, Pascal, Die Haftung bei geführten Sportangeboten mit erhöhtem Risiko, Diss. Luzern 2012; Oser, David/Weber Rolf H., in: Widmer Lüchinger, Corinne/Oser, David (Hrsg.), Basler Kommentar zum Obligationenrecht, Bd I, 7. Aufl., 2020; Paramalingam, Sridar / Geser, Marcel, Base Jump, in: Anne Mirjam Schneuwly/Rahel Müller (Hrsg.), Bergsportkommentar; Trechsel, Stefan /Jean-Richard, Marc, in: Stefan Trechsel/Mark Pieth (Hrsg.), Schweizerisches Strafrecht, Allgemeiner Teil, Bd. I, 4. Aufl., 2011; Vuille, Miro, Wandern, in: Anne Mirjam Schneuwly/Rahel Müller (Hrsg.), Bergsportkommentar ; Wiegand, Wolfgang, in: Widmer Lüchinger, Corinne/Oser, David (Hrsg.), Basler Kommentar zum Obligationenrecht, Bd I, 7. Aufl., 2020.

Materials

Botschaft vom 25. Mai 2016 zum Bundesgesetz über das Stabilisierungsprogramm 2017-2019 sowie zum Bundesgesetz über Aufgaben, Organisation und Finanzierung der Eidgenössischen Stiftungsaufsicht, BBl 2016 5691; Stabilisierungsprogramm 2017-2019, Erläuternder Bericht für die Vernehmlassung vom 25. November 2015 (zit. Erläuternder Bericht 2015); Stellungnahme des Bundesrates vom 26. August 2009 zum Bericht vom 27. März 2009 der Kommission für Rechtsfragen des Nationalrates zur Parlamentarischen Initiative 00.431 Rahmengesetz für kommerziell angebotene Risikoaktivitäten und das Bergführerwesen, BBl 2009 6051; Bericht der Kommission für Rechtsfragen des Nationalrats vom 27. März 2009 zur Parlamentarischen Initiative 00.431 Rahmengesetz für kommerziell angebotene Risikoaktivitäten und das Bergführerwesen, BBl 2009 6013; Stellungnahme des Bundesrates vom 14. Februar 2007 zum Bericht vom 1. Dezember 2006 der Kommission für Rechtsfragen des Nationalrates zur Parlamentarischen Initiative 00.431 Rahmengesetz für kommerziell angebotene Risikoaktivitäten und das Bergführerwesen, BBl 2007 1537; Bericht der Kommission für Rechtsfragen des Nationalrats vom 1. Dezember 2006 zur Parlamentarischen Initiative 00.431 Rahmengesetz für kommerziell angebotene Risikoaktivitäten und das Bergführerwesen, BBl 2007 1497.

I. Introduction and overview of mountain sports

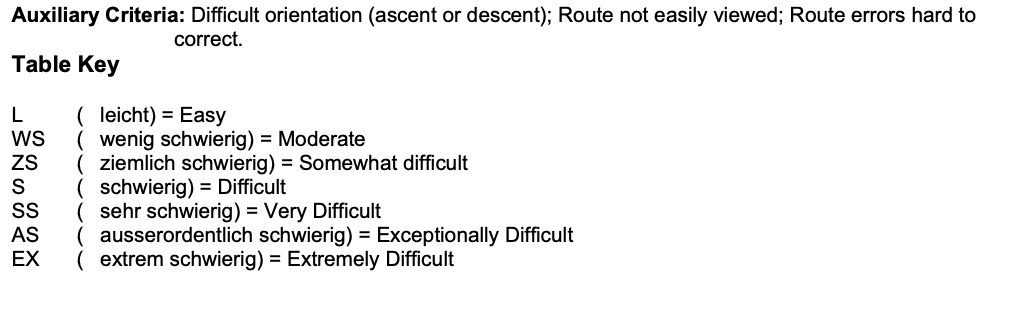

As a basis for the mountain sports commentary, the term mountain sports shall be defined at the beginning and a short overview of the mountain sports shall be given. Then, the difficulty scales of the SAC should be mentioned. The difficulty scales do not only enable mountaineers to assess whether an activity is appropriate to their concerns, abilities and possibilities, but they can also be of importance in the possible legal assessment of a mountain accident. If a mountain accident occurs, the criminal and civil law assessment of possible breaches of the duty of care must include an allocation of risk in order to distinguish the personal responsibility of the mountain climber from the legal responsibility of a third party. The SAC difficulty scales play a key role here: they define requirements at a general abstract level and thus create the basis for a legal assessment. The same applies to a possible reduction of social security claims: when assessing an action (risk, gross negligence), the action must first be classified objectively - here, too, the SAC difficulty scales can serve.

A. Term mountain sports

There is no generally binding definition of what is meant by mountain or alpine sports. In general, it includes a wide range of activities that are carried out in the mountains (see also Galli, p. 7 and Müller, Haftungsfragen, para. 12). However, a glance at the structure of the present commentary already shows that even the connecting factor "mountains" does not apply conclusively: for example, multi-pitch climbing routes outside the mountains (cf. Hungerbühler, n. 8), hikes in the lowlands (cf. Vuille, n. 7) or mountain bike tours in lower-lying forests (cf. Hogrefe, n. xx) are also covered by this generic term.

The list in this commentary is also not to be understood as exhaustive. The term "mountain sports" also includes activities that are not (yet) specifically dealt with in this commentary.

The Swiss Alpine Club SAC also has to deal with the question of which sports it would like to include under mountain sports and promote accordingly. For example, various SAC sections offer indoor climbing courses - a discipline that at first glance may not be recorded as a mountain sport activity (cf. on climbing Hungerbühler, passim). On the other hand, the Swiss Alpine Club does not (yet) offer certain mountain sports activities (e.g. Base Jump - cf. Paramalingam/Geser, passim).

B. Difficulty scales of the Swiss Alpine Club SAC

The Swiss Alpine Club SAC has published difficulty scales for individual mountain sports (available at: https://www.sac-cas.ch/de/ausbildung-und-sicherheit/tourenplanung/schwierigkeitsskalen/). The scales are of great importance, especially in the preparation of mountain sports activities, because they present the respective requirements in a short and accessible way. Under the heading of personal responsibility, mountaineers are expected to clarify and question whether they are technically, physically and psychologically up to the activity before starting it (see also Müller, Haftungsfragen, para. 34).

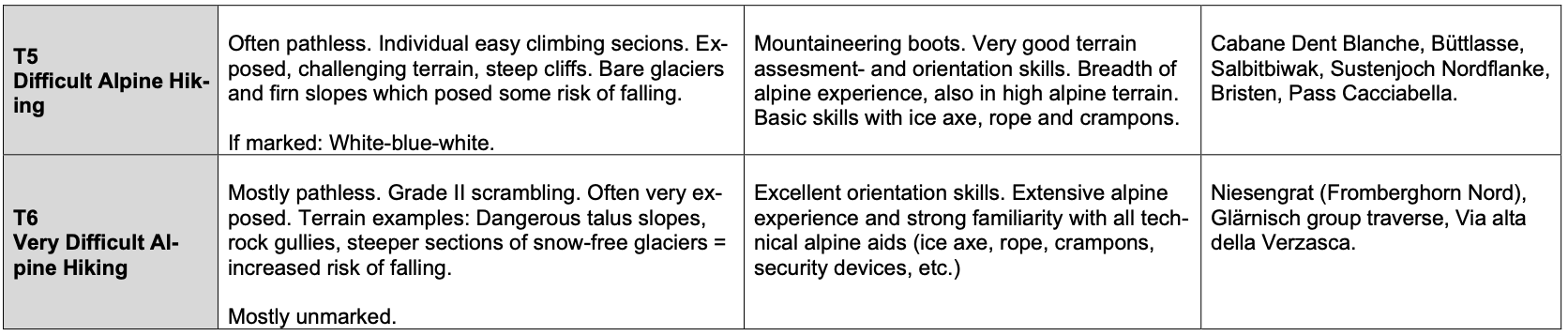

1. Mountain and Alpine Hiking Scale

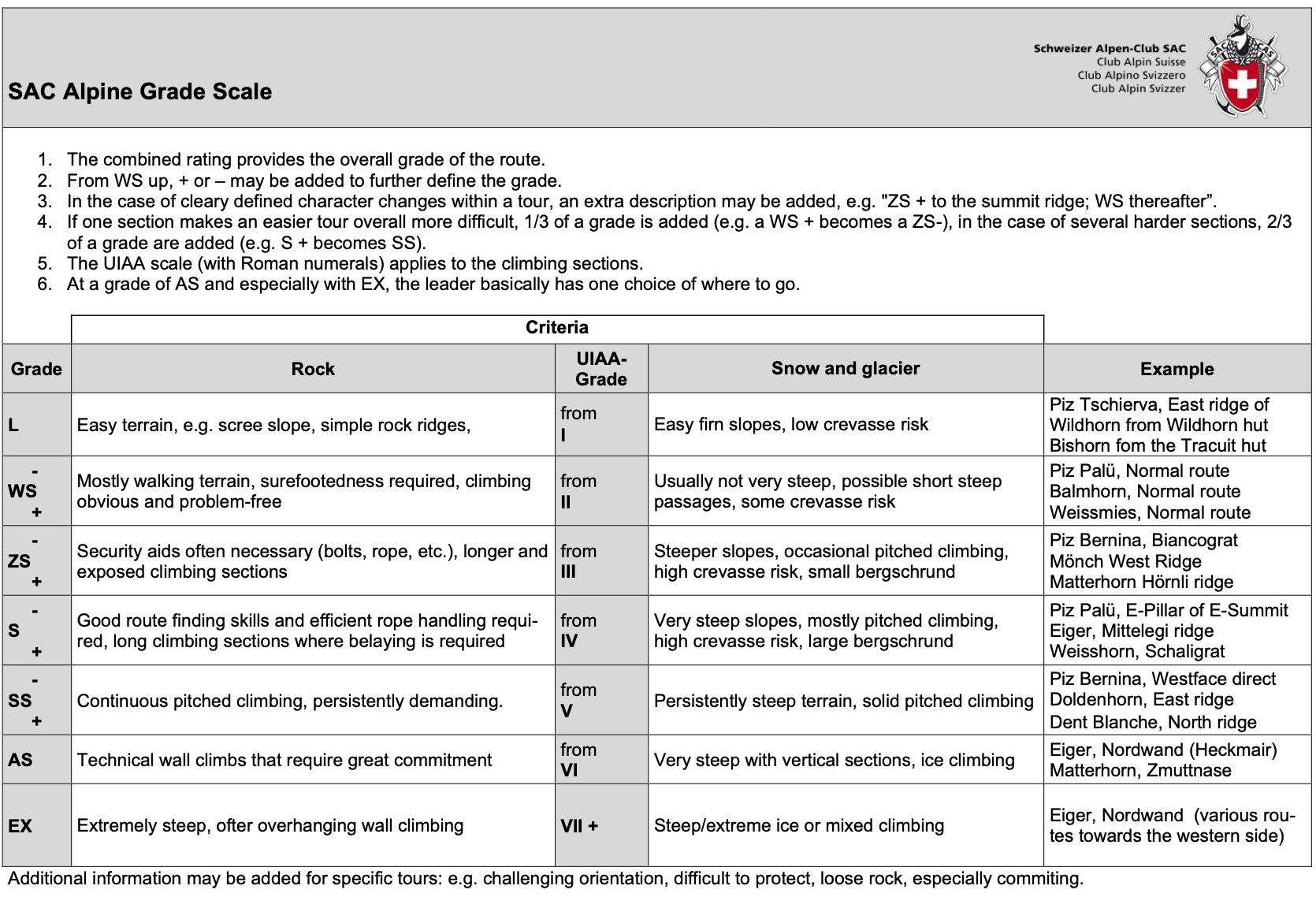

2. High tour/alpine grade scale

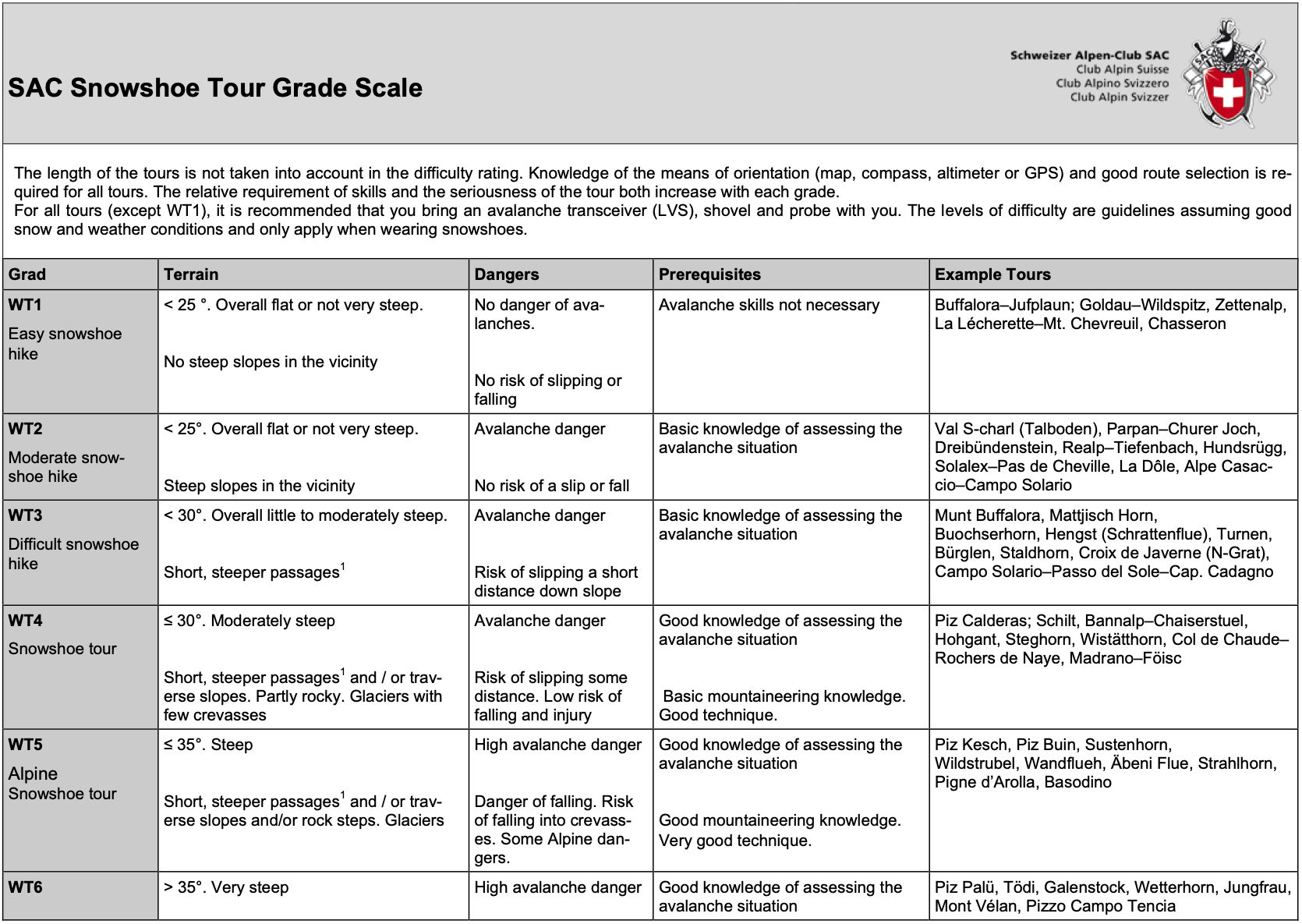

3. Snowshoe tour grade scale

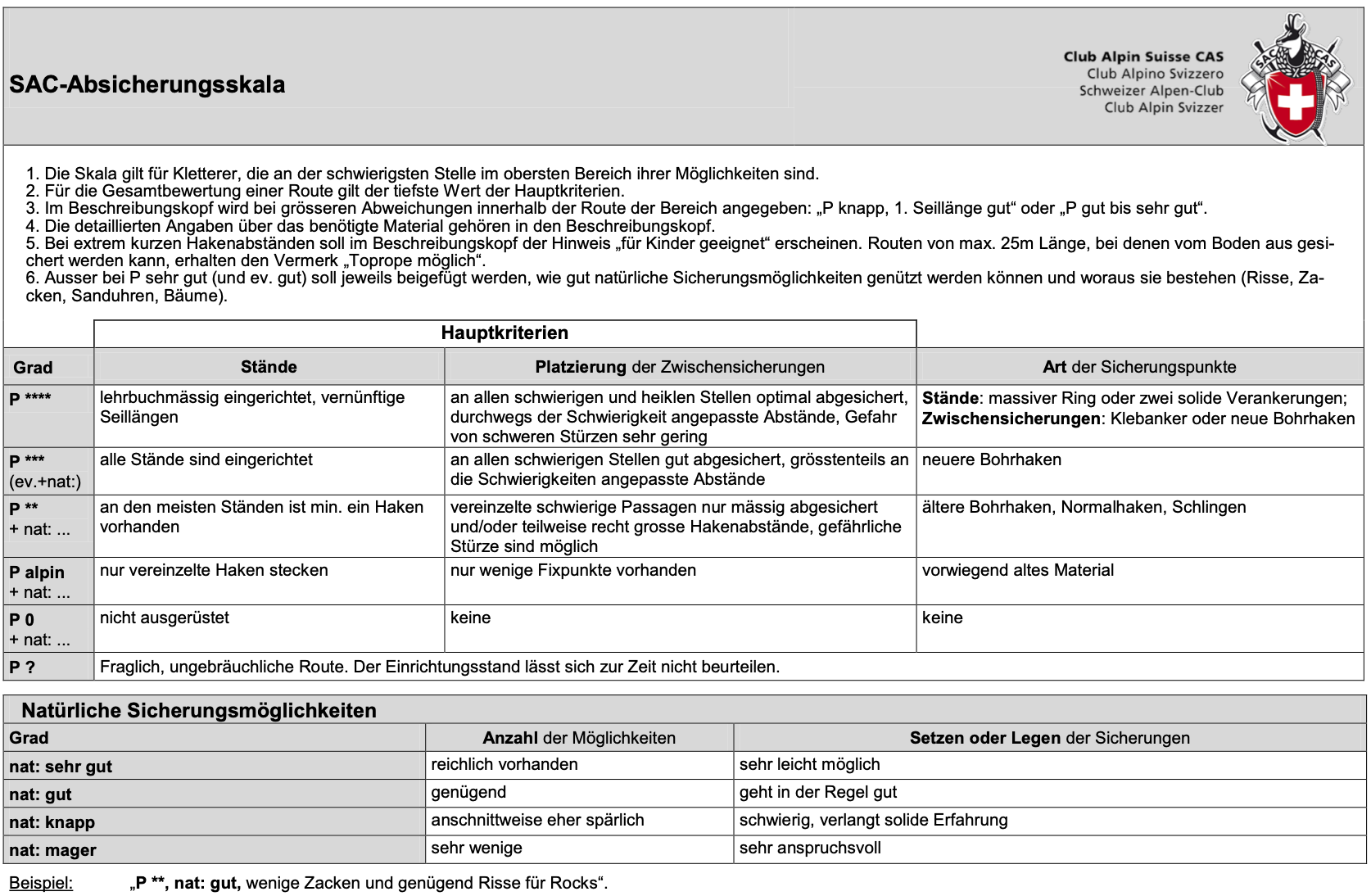

4. Hedging scale

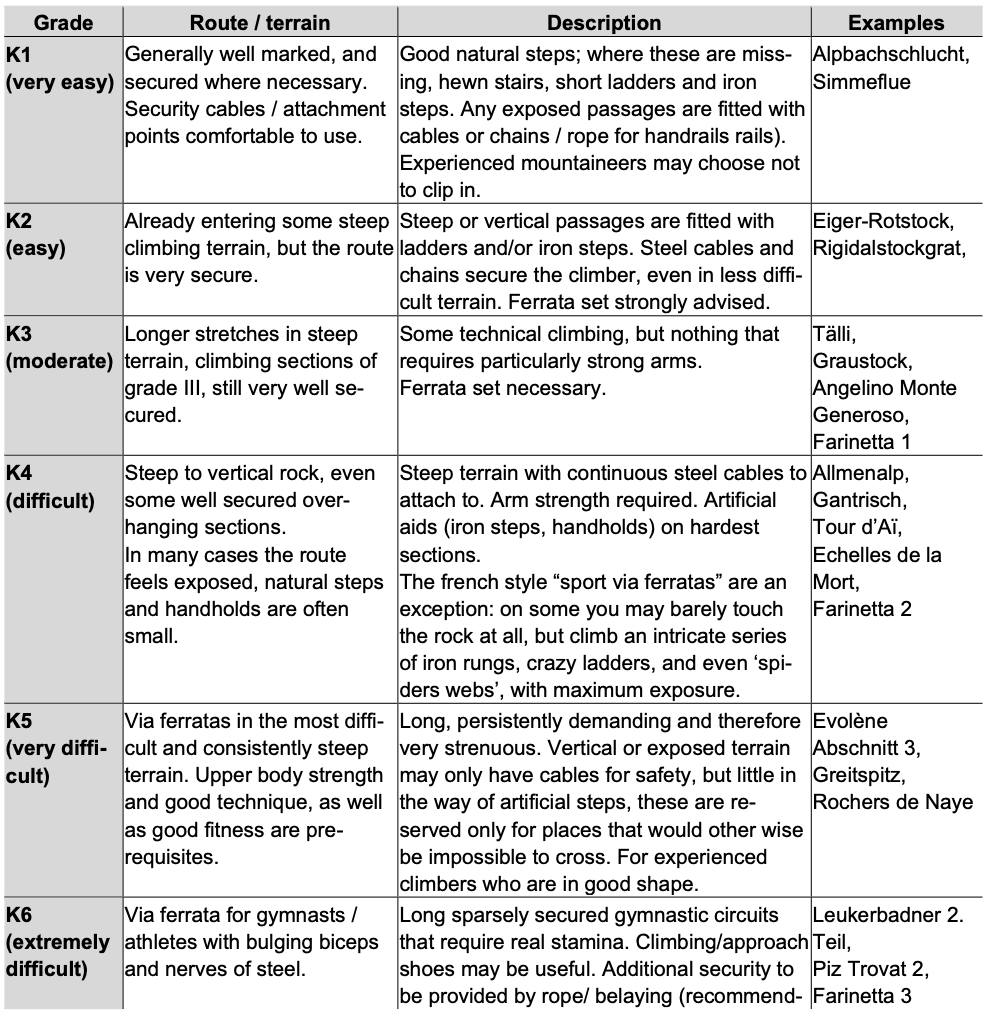

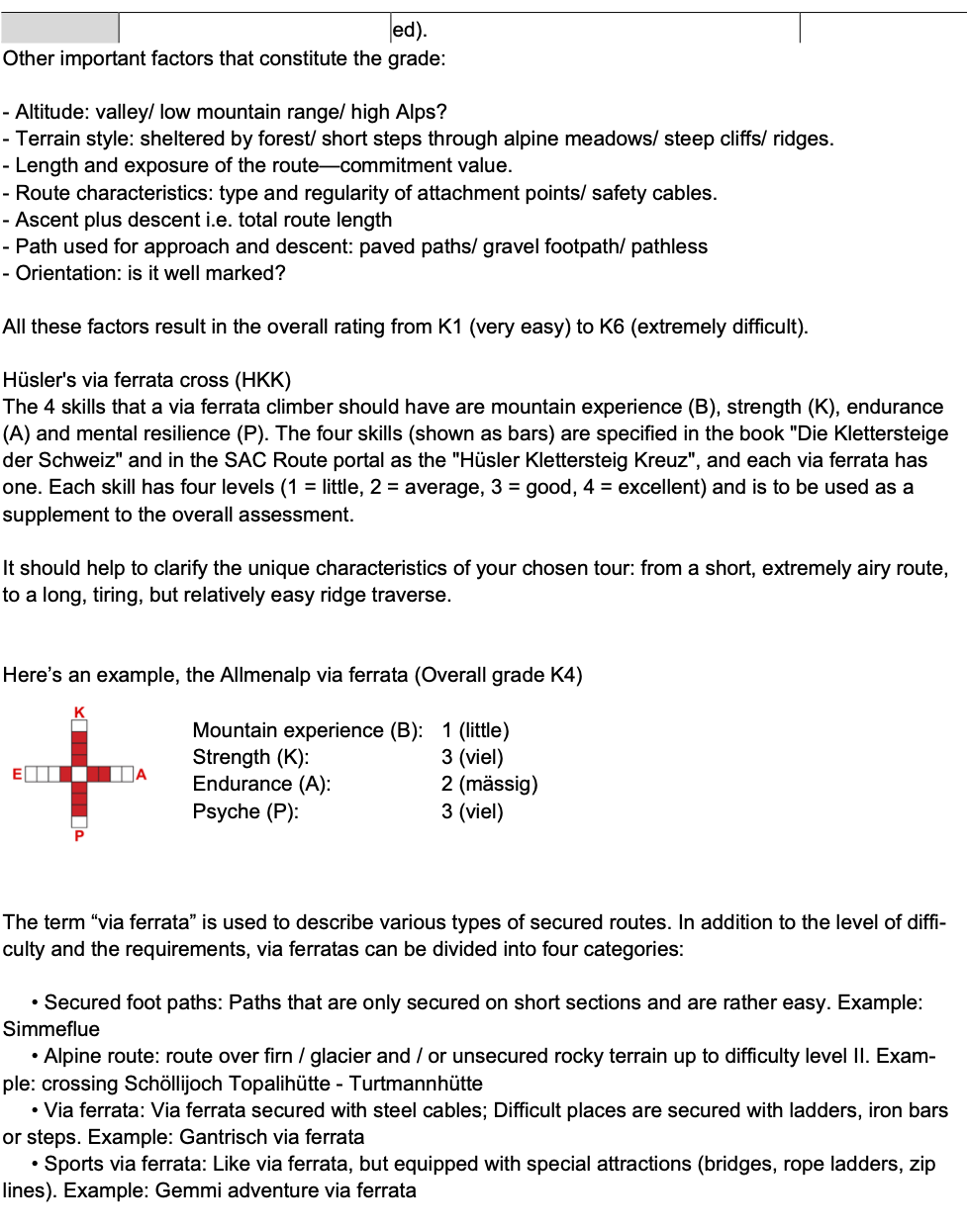

5. Via ferrata scale

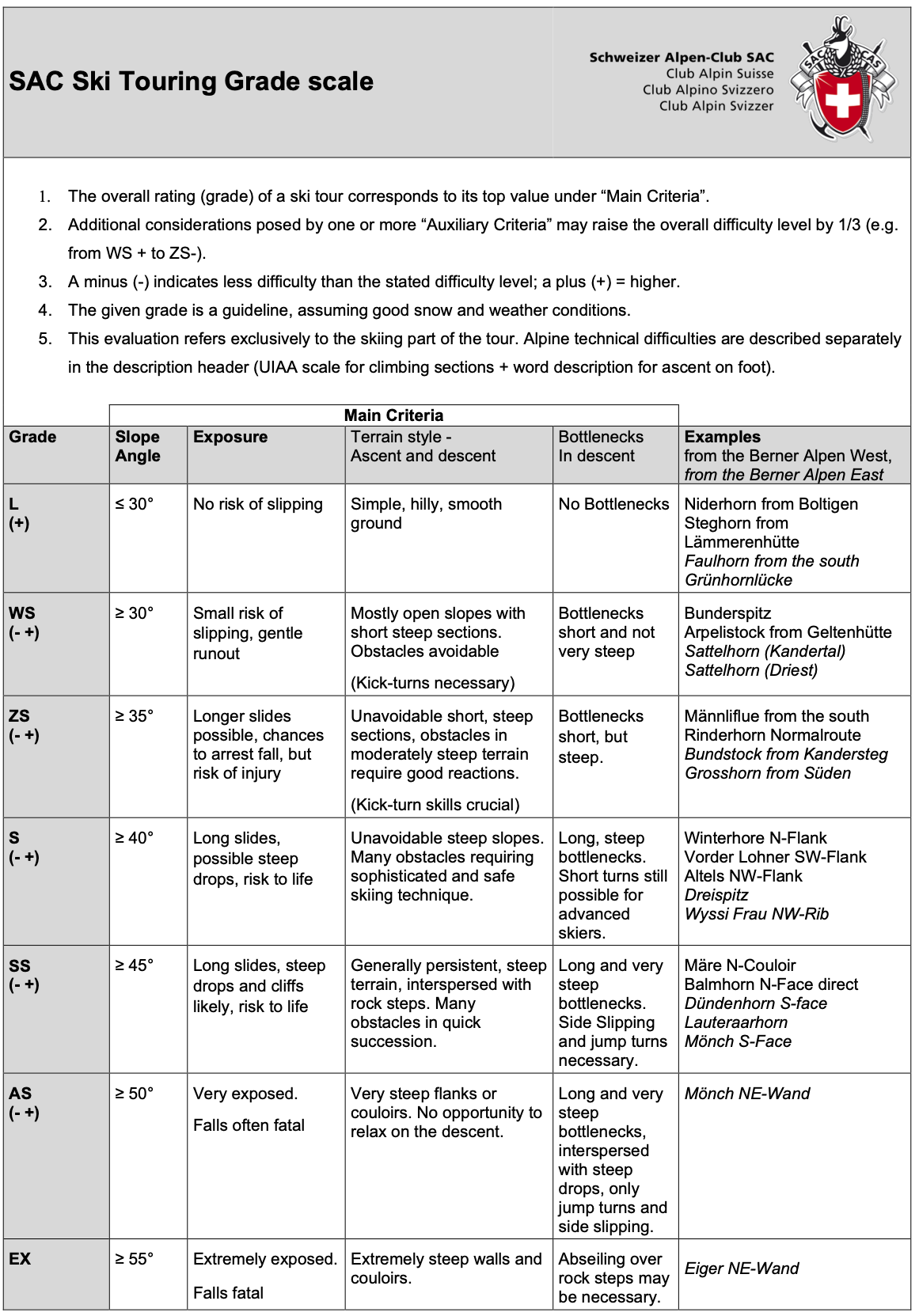

6. Ski touring grade scale

II. Legal basis

The practice of mountain sports affects a wide variety of legal areas: starting with the question of the right of "access" to the mountains (art. 699 of the Swiss Civil Code), through a wide variety of environmental and nature conservation regulations, to questions of responsibility under civil and criminal law, as well as the social security consequences of mountain accidents.

The present paper presents the legislation on risk activities, the basis of liability under civil law, some principles of social insurance law, and approaches to the criminal law assessment of mountain accidents. Specific explanations can be found in the articles to the individual mountain sports.

A. Risk Activities Act

1. Initial background

It is now over 20 years since 21 young people lost their lives in a canyoning accident in the Saxetbach, Bernese Oberland. The accident led to a conviction of six employees of the responsible outdoor company for negligent homicide (Müller, Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung, p. 94). The provider was criminally accused of not having carried out a risk analysis and, based on this, not having taken safety measures. The accused guides, on the other hand, were acquitted of the charge of negligent homicide. Only one year later, a bungee jump in Stelchelberg ended fatally - the (same) provider had used the wrong or too long rope for a bungee jump. These accidents triggered a political discussion on the extent to which commercially offered risk activities and mountain guiding should be regulated (see also the summary in BBl 2009 6051 as well as in the further materials: BBl 2009 6013, BBl 2007 1537 and BBl 2007 1497).

On January 1, 2014, the risk activities legislation (Federal Law of March 17, 2010 on Mountain Guides and the Provision of Other Risk Activities [RiskG], SR 935.1 and Ordinance on Mountain Guides and the Provision of Other Risk Activities of November 30, 2012, Risk Activities Ordinance [RiskV], SR 935.911) came into force. The legislation regulates the licensing, certification and insurance obligations for providers of so-called risk activities and defines due diligence obligations.

2. Political discussion after enactment

Barely two years after the Risk Activities Act came into force, the Federal Council opened a consultation on repealing the Risk Act as part of the 2017-2019 stabilization program. In the explanatory report, the Federal Council stated that experience with the law showed that it would not create any additional security (Explanatory Report 2015, p. 68). The proposed repeal was rejected by a majority of the cantons, parties and associations concerned, which is why the Federal Council then requested in its dispatch to parliament that the repeal of the RiskG be dispensed with (BBl 2016 5691, p. 4769 and 4770). From a political point of view, this development is already significant: while the parliamentary discussion and adoption of the legislation took many years - which is an expression of the fact that the introduction of the regulation was controversially assessed - there was now a majority consensus that a repeal of the legislation is not desired.

From March 28 to July 5, 2018, the Federal Council conducted a consultation process on the amendment of the RiskV and, based on the findings, put the revised ordinance into force as of May 1, 2019. On the one hand, the total revision of 2019 shows the rapid development of the various trends of the sports covered. On the other hand, it is also an indication that the legislator has entered new territory here and that legislation and practice are still in an approximation phase.

It remains to be seen with excitement whether and what clarifications a next revision will bring.

3. Most important contents at a glance

a. Scope

aa. Activity

The risk activity legislation lists criteria that qualify an activity as a risk activity. Thus, art. 1 para. 1 RiskG states that the commercial offering of risk activities in mountainous or rocky terrain or in stream or river areas where there is an increased risk (namely: danger of falling or slipping or an increased risk due to swelling water masses, falling rocks and ice or avalanches) and where special knowledge/safety precautions are required to undertake the activity is subject to the risk activities legislation (cf. also Müller, Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung, p. 95). art. 3 para. 1 RiskG then contains an exhaustive list of the activities covered.

bb. Provider

Furthermore, the law designates the activities of mountain guides, snow sports instructors outside the area of responsibility of operators of ski lifts and cable cars, canyoning, river rafting, white water descents and bungee jumping as risk activities (art. 1 para. 2 RiskG). At the ordinance level, the activities of mountain guide aspirants, climbing instructors and hiking guides are also subject to the law (art. 1 RiskV).

cc. Commercial offering

Only the commercial offering of risk activities is covered (art. 1 para. 1 RiskG). Anyone who carries out a risk activity privately (alone or in a group) is not affected by the legislation (see also Müller, Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung, p. 96). While the original ordinance text (version of 30 November 2012) set a turnover limit of CHF 2300 for the criterion of professionalism, the version in force since April 2020 in art. 2 para. 1 RiskV states that any provider who earns a fee on the territory of the Swiss Confederation is acting professionally.

It is also clear from the materials that tour leaders of alpine associations are not covered by the scope. Their remuneration is a token expense allowance that usually only covers expenses (BBl 2009 6013, p. 6029). In concrete terms, this means that SAC tours are not covered by the risk activities legislation.

b. Due diligence

According to the general clause of art. 2 para. 1 RiskG, providers of risk activities must "take the measures that are necessary according to experience, possible according to the state of the art, and appropriate according to the given circumstances, so that the lives and health of the participants are not endangered". This formulation is based on the general danger theorem, which obliges the person who creates or maintains a condition that could harm another to take the precautions necessary to avoid harm (Bütler, p. 112; Müller, Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung, p. 97).

Art. 2 para. 2 RiskG then contains a non-exhaustive list of duties: Participants in risk activities must be informed about special dangers (lit. a) and it must be checked whether they have sufficient capacity to perform the chosen activity (lit. b). The absence of defects in the equipment and any installations must be ensured (lit. c). The suitability of the weather and snow conditions must be checked (lit. d) and the qualification of the personnel must be ensured (lit. e). It must also be ensured that sufficient escorts are available according to the level of difficulty and danger (lit. f). Finally, consideration must be given to the environment and the habitats of animals and plants must be protected (lit. g).

The risk activities legislation does not create any civil liability, but defines duties of care, the breach of which may give rise to liability (Müller, Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung, p. 98; Nosetti, para. 1184). Furthermore, according to the opinion represented here, the duties of care defined in the risk activities legislation do not go further than those already arising from general contract law.

c. Authorization requirement

The Risk Activities Act stipulates a licensing requirement for the commercial offering of risk activities (art. 3 RiskG).

aa. Permit for mountain guides

Mountain guides receive a permit if they have a federal certificate of proficiency (art. 43 of the Vocational Training Act of 13 December 2002; BBG, SR 412.10) or an equivalent Swiss or foreign certificate of proficiency, if they offer a guarantee of compliance with the obligations under the RiskG and if they have taken out professional liability insurance (art. 4 Para. 1 and art. 13 RiskG).

Mountain guides with a corresponding permit are then authorized to offer the following activities (art. 4 para. 1 RiskV in conjunction with art. 3 para. 1 lit. a-h RiskV):

- High tours

- Alpine hiking

- Tours with skis, snowboards and similar snow sports equipment

- Snowshoe tours

- Variant descents

- Climbing via ferrata

- Icefall and steep ice climbing

- Climbing

- Canyoning, provided that the mountain guide has an additional training of the Swiss Mountain Guide Association (SBV) or a diploma recognized by the IVBV.

The permit for aspiring mountain guides entitles them to carry out the activities listed above, provided that this is done under the direct or indirect supervision and co-responsibility of a mountain guide with a permit (art. 5 RiskV).

bb. Authorization for snow sports instructors

Snowsport instructors receive a permit for guiding clients outside the area of responsibility of operators of ski lifts and cable cars, if they have a federal certificate of proficiency (art. 43 BBG) or an equivalent domestic or foreign certificate of proficiency, if they guarantee compliance with the obligations according to the RiskG and if they have taken out professional liability insurance (art. 5 and art. 13 RiskG).

Snowsport instructors with the appropriate authorization are then authorized to offer the following activities (art. 7 RiskV):

- Tours with skis and snowboards up to max. difficulty WS

- Snowshoe tours up to max. difficulty WT3

- Variant descents up to max. difficulty level S (new since 2019 - previously ZS), provided there is no risk of falling

However, all activities may be offered only if in the specific activity:

- no glaciers are crossed, and

- apart from snow sports equipment, skins, crampons and snowshoes, no other technical aids such as ice picks, crampons or ropes need to be used to ensure the safety of the customers.

cc. Approval for climbing instructors

Climbing instructors receive a permit for climbing with more than one rope length with clients (cf. Hungerbühler, n. 8) if they have a federal certificate of proficiency (art. 43 BBG) or an equivalent domestic or foreign certificate of proficiency, they offer a guarantee of compliance with the obligations under the RiskG and have taken out professional liability insurance (art. 6 and art. 13 RiskG, art. 6 RiskV).

The ascent or descent to the climbing point is allowed (art. 6 para. 1 RiskV):

- do not require walking on a short rope (however, it is permissible to secure the customer from a secured stand);

- do not require crossing glaciers, and

- not require the use of technical aids such as ice axes or crampons.

Climbing with clients over one rope length is not subject to the risk activities legislation and can therefore be offered freely - even commercially (art. 3 para. 1 lit. h RiskV e contrario). However, in accordance with the spirit and purpose of the legislation, the requirements for access/descent (art. 6 para. 1 RiskV) must also be complied with. Depending on the design of the access/descent to a climbing passage, this must therefore be carried out under the responsibility of a mountain guide, if a commercial offer exists.

For climbing via ferrata with clients (art. 3 para. 1 lit. f RiskV) the completion of an additional training is required (art. 6 para. 4 RiskV). Climbing instructors in training may then carry out climbing tours with more than one rope length under the direct supervision and responsibility of a person with a permit, provided this is necessary for the training (art. 6 Para. 5 RiskV).

dd. Permit for hike leaders

The offering of hikes up to the level of difficulty T3 (hiking and mountain hiking) does not fall under the risk activities legislation (art. 3 para. 1 lit. b e contrario) and can therefore be offered - commercially - without a permit, even by persons who are not hiking guides (cf. also Vuille, para. 15).

Hiking guides are granted a permit to accompany clients on alpine hikes with a level of difficulty of T4 and on snowshoe tours with a maximum level of difficulty of WT3 if they hold a federal certificate of proficiency (art. 43 BBG) or an equivalent Swiss or foreign certificate of proficiency, if they guarantee compliance with the obligations under the RiskG and if they have taken out professional liability insurance (art. 6 and art. 13 RiskG, art. 8 RiskV).

For snowshoe tours, the restrictions (art. 8 para. 1 RiskV) apply that no glaciers are crossed and, apart from snowshoes, no technical aids such as ice axes, crampons or ropes must be used to ensure the safety of the clients. In order to offer alpine hiking tours (T4), additional training is also required, which covers the area of safety and risk management in alpine hiking. Hiking guides in training may then carry out the above activities under the direct supervision and responsibility of a person with a permit, provided this is necessary for the training (art. 6 para. 5 RiskV).

At this point, a question mark is allowed regarding the restriction of taking a rope with you: Considering on the one hand that the commercial offering of single-pitch climbing routes is not subject to the risk activities legislation and on the other hand that it can be in the interest of all parties involved that a key point is secured by means of a rope, the restriction of art. 8 Para. 1 lit. c RiskV (as well as art. 8 Para. 4 lit. c in connection with art. 8 Para. 1 lit. c RiskV) appears to be not very practice-oriented and too strict. It is convincing that walking on a short rope (if offered commercially) is reserved for mountain guides. However, according to the opinion represented here, belaying from a belaystation should also be possible for hiking guides, provided they have the necessary additional training (art. 8 para. 4 lit. b RiskV), in order to be able to offer T4 tours with as little risk as possible.

ee. Authorization for other providers of risk activities

Article 9 RikV then regulates the authorization for leaders of white water rafting. For the other providers of risk activities, a certification is required for the implementation of the corresponding activity (art. 10 RiskV). These providers must also guarantee compliance with the obligations under the RiskG and have taken out professional liability insurance (art. 6 and art. 13 RiskG).

B. Basis of liability

1. Introductory remarks

Under civil law, the relationship between providers of mountain sports activities and mountain sports enthusiasts is usually a contractual relationship according to art. 394 ff. of the Swiss Code of Obligations.

The contractors are liable to the clients if the latter are injured due to careless or unfaithful performance of the assigned business (art. 398 para. 2 CO). If a negligent conduct of the contractor leads to bodily injury or death of a client, this may in individual cases lead to claims for damages and/or satisfaction of the injured person or the surviving dependants (art. 398 para. 2 in conjunction with art. 97 para. 1 CO; art. 99 para. 3 in conjunction with art. 47 CO).

In addition, there is a competing claim for liability in tort (art. 41 para. 1 CO).

Risk activity legislation, on the other hand, does not provide a basis for liability.

2. Personal responsibility on the mountain

If a mountain accident leads to a damage relevant under liability law (see below para. 43), this can only be passed on to third parties if and insofar as there is no personal responsibility for the damage. In concrete terms, this is about a demarcation of risk spheres: If a person calls in a professional - for example a mountain guide - to carry out a mountain sport activity, part of the personal responsibility is transferred to the guide. However, even in this case, the residual alpine risk remains with the person being guided. Examples of the residual alpine risk are stone/rock eruptions or stumbling falls on terrain that was not to be secured or also ex ante unforeseeable avalanches (Müller, Haftungsfragen, para. 31 ff., with further references).

Personal responsibility includes the duty of the alpinist to carry out the activity according to his or her abilities, to make the necessary preliminary clarifications regarding the degree of difficulty and to equip him- or herself sufficiently. Aborting a tour is also part of personal responsibility (Müller, Haftungsfragen, para. 34).

The principle of personal responsibility applies to all conceivable liability constellations and must also be taken into account in the criminal law assessment (Müller, Haftungsfragen, paras. 28 and 33).

3. In particular: Damage

The damage is measured according to the difference theory: The current financial status of the injured party is compared with the hypothetical financial status in the absence of the damaging event (instead of many BSK-Kessler, Art. 41 OR N 3).

In the case of mountain accidents, the following types of damage are particularly relevant (cf. Müller, Haftungsfragen, para. 49, m.w.H.):

- Personal injury: Rescue and transport costs, medical and nursing care costs, loss of earnings, salvage and burial costs, as well as utility damage;

- Material damage: Value of the material carried;

- Frustration damage: e.g. claim for compensation for expenses already paid, such as travel costs, overnight accommodation in a hut already paid for or mountain guide costs. According to prevailing doctrine and case law, frustration damages are not compensated.

4. Contractual liability

In the case of a commercially offered tour - but also in the case of SAC tours - a contractual relationship exists between the provider and the guest. The liability is based on art. 398 Abs. 2 i.V.m. art. 97 para. 1 OR. The preconditions are damage (cf. para. 43 above), a causal connection between the damaging conduct and the damage incurred as well as fault. However, the latter is generally presumed in the case of contractual liability (instead of many BSK-Wiegand, art. 97 OR N 42). The provider then has to take into account the possible misconduct of the leading person under the title of auxiliary person liability (art. 101 OR).

In the case of mountain accidents, the question of fault and thus the breach of the duty of care plays a central role. As explained, the risk activities legislation standardizes certain duties of care (cf. marg. no. 17 above). The due diligence owed under the contract law is then determined in the specific individual case and is therefore also dependent on the experience of the person being guided. The person in charge is required to exercise the same diligence that a conscientious person would exercise in the same situation, taking into account the specific content of the contract, when handling the business entrusted to him (BSK-Oser/Weber, Art. 398 OR N 24). For the specific duties of care of consulted guides, reference is made to the contributions in the BT. It should always be noted that the personal responsibility of the guests is not rendered irrelevant by the involvement of a guide (Müller, Haftungsfragen, para. 302).

5. Liability in tort

Like contractual liability, tort liability (liability for fault, art. 41 OR) requires unlawfulness and fault in addition to the existence of causally caused damage (cf. supra para. 43). The burden of proof for the existence of the liability requirements lies with the injured party.

With regard to fault (breach of duty of care), reference can be made to the comments on contractual liability.

6. Works owner liability

While tort liability requires fault, art. 58 OR offers the possibility to hold the owner of a building or other work liable for the damage it causes as a result of faulty installation or production or poor maintenance, regardless of fault (causal liability). This could be relevant in the case of hiking accidents: According to doctrine and jurisprudence, hiking trails have the character of a work if the trail has been artificially created by considerable removal, blasting and filling or has been provided with structural constructions or safety elements (cf. Müller, Haftungsfragen, para. 75 ff., with further references; Vuille, para. 40). But also in the case of climbing accidents, a work owner liability can come into play (cf. Hungerbühler, marg. no. 43).

7. Further bases of liability

In addition to contractual liability and liability in tort, other bases of liability may also come into question in individual cases. For example, a possible liability based on trust is to be considered (cf. Müller, Haftungsfragen, para. 104).

Finally, a special case is the danger posed by animals, such as guard dogs, mother cows or bulls (Müller, Haftungsfragen, marg. no. 49). Relevant here is the animal owner's liability according to art. 56 OR (cf. on the whole Vuille, marg. no. 73).

C. Criminal Law

1. Relevant offenses

In terms of criminal law, the provisions of negligent homicide (art. 117 StGB) and negligent bodily injury (art. 125 StGB) are particularly relevant in the case of mountain accidents.

2. In particular: Imprudence contrary to duty

The negligent commission of a felony or misdemeanor requires imprudence in breach of duty. This is the case if the offender fails to exercise the caution to which he or she is obliged under the circumstances and according to his or her personal circumstances (art. 12 para. 3 SCC).

According to the case law of the Federal Supreme Court, a person acts in breach of due care if, at the time of the act, on the basis of the circumstances as well as knowledge and skills, he or she could and should have recognized the resulting risk to the legal interests of the victim and at the same time exceeded the limits of the permissible risk. The degree of care to be exercised is primarily determined by these regulations, where special standards for accident prevention and safety require a certain behavior. In the absence of such regulations, analogous rules of (semi-)private associations may be used, provided that these are generally accepted. However, the accusation of negligence can also be based on general legal principles such as the principle of risk. The imputability of the success requires foreseeability according to the standard of adequacy. Furthermore, it is assumed that the success was avoidable. Under the hypothetical causal process, it is examined whether the success would not have occurred if the perpetrator had acted dutifully. For the attribution of the success, it is sufficient if the conduct of the perpetrator at least with a high degree of probability forms the cause of the success (BGer 6B_535/2019 of 13 November 2019, E. 1.3.1; BGE 135 IV 56, E. 2.1., m.H.; BGer 6B_351/2017 of 1 March 2018, E.1.3.1).

In principle, in the case of mountain accidents, the duty of care that is relevant under criminal law corresponds to the duty of care that is owed under civil law and that is relevant under liability law in the event of its violation (cf. however the explanations on art. 53 OR below under No. 4).

3. Commitment by omission

In the case of accidents in the mountains, it is regularly examined whether there was an act of omission. This is obvious insofar as in every accusation of negligence there is an omission, namely the non-observance of a duty of care (Trechsel/Jean-Richard, § 17 N 1).

For example, if a piste manager (contrary to his duty) fails to close a ski area despite an increased avalanche danger and an avalanche then buries the piste, this can lead to a conviction for negligent homicide by omission (BGE 138 IV 124). Also the director of a cableway who fails to interrupt the operation despite knowledge of a technical problem may be liable to prosecution for involuntary manslaughter by omission if a person is killed in an accident (BGE 122 IV 61). Another case - often cited in the doctrine - concerns the husband who, despite bad weather, takes his wife, who is not very used to the mountains and inexperienced in skiing, on a ski tour, does not choose the shortest and easiest route, does not turn back when the weather changes, spends the night in snow and ice without taking measures to protect his wife against the cold and finally leaves her in the morning hours (whereupon she dies). Here, too, negligent homicide by omission was affirmed (BGE 83 IV 9).

However, according to prevailing doctrine and case law, the subsidiarity theory applies in Switzerland: An accusation is primarily to be understood as an act, as long as there is a legally causal act (BSK-Niggli/Muskens, Art. 11 StGB N 53). In the case of an offense of commission, the accusation consists of having caused a success by an act, and in the case of an offense of omission, of not having averted the success by active action (BSK-Niggli/Muskens, Art. 11 StGB N 52). In practice, the demarcation is often difficult. The Supreme Court of the Canton of Bern had to deal with the following facts: A mountain guide failed to secure two girls entrusted to him by means of a rope during the ascent to a rappel point. This resulted in a fatal fall of one of the girls. The Supreme Court held that this was not an omission. Rather, the mountain guide was accused of an act: Namely, the guiding without rope safety (judgment of the Superior Court of the Canton of Bern of January 25, 2019, SK 18 12, N 16). As a result, the mountain guide in question was acquitted (in the opinion represented here in a correct manner), since the mountain guide was "within the range of the permitted risk" in his actions.

Offenses of omission require the existence of a qualified legal obligation (guarantor position) (BSK-Niggli/Muskens, Art. 11 StGB N 6). Guiding persons (such as mountain guides, tour leaders, hiking guides, climbing instructors) but also de facto guides will regularly be in a position of guarantor.

4. Civil and criminal proceedings

Since conduct in breach of duty on the occasion of a mountain sports activity that is relevant under civil law is regularly also relevant under criminal law, or could be, an injured person will often consider taking both civil law and criminal law steps.

In this regard, art. 53 para. 1 OR must be observed, which states that the civil judge is not bound by an acquittal by the criminal court, in particular when assessing guilt or non-guilt. Likewise, the criminal court's finding with assessment of guilt and determination of damage is not binding for the civil judge (art. 53 para. 2 OR). This provision does not apply if the injured person falls under the definition of victim in art. 1 of the Federal Law on Assistance to Victims of Crimes of 23 March 2007 (OHG, SR 312.5) and the civil point is either decided adhesion-wise in criminal proceedings or a civil court has to determine the amount of the civil claim after a criminal judge has ruled in principle on the civil point (BSK-Kessler, Art. 53 OR N 2a).

For more detailed procedural questions, please refer to the article by Müller/ Sidiropoulos.

D. Social insurance law

1. Introductory remarks

Employees (incl. trainees) in Switzerland are obliged to take out accident insurance including non-occupational accidents (art. 1a para. 1 and art. 6 para. 1 of the Federal Law on Accident Insurance of 20 March 1981 [UVG, SR 832.20]).

Under insurance law, an accident is understood to be "the sudden, unintentional damaging effect of an unusual, external factor on the human body, resulting in impairment of physical, mental or psychological health or death" (art. 4 of the Federal Law on the General Part of Social Insurance Law of October 6, 2000 [ATSG, SR 830.1]). Typical liability-relevant mountain accidents, such as a fall, will for the most part clearly qualify as an accident (Müller, Haftungsfragen, marg. no. 385).

2. Benefit reductions / denials

a. Basics

Culpable - namely grossly negligent - causation of damage (art. 37 UVG) and the assumption of an exceptional risk or hazard (art. 39 UVG) may lead to benefit reductions or even denials.

The reason given for this regulation is that premium payers should not be burdened with too great a financial burden if insured persons expose themselves to extraordinary risks and have an accident (cf. Müller, Haftungsfragen, para. 388).

Depending on the type of mountain sport and the way in which it is practiced, it makes sense for mountaineers to take out special insurance under private law in order to ensure sufficient insurance cover in the event of damage - especially for surviving dependents.

b. Grossly negligent causation

According to the case law of the Federal Supreme Court, gross negligence is understood to be the disregard of the elementary precautionary rules that any reasonable person in the same situation and under the same circumstances would have followed in order to avoid an injury that was foreseeable according to the natural course of events (BGE 138 V 522, 527, E. 5.2.1; 121 V 40, 45, E. 3b; 118 V 305, 306, E. 2). The concrete circumstances of the individual case are decisive. For examples, please refer to the individual articles on mountain sports.

c. Venture

The Federal Council may designate exceptional hazards and risks that lead to the denial of all benefits or the reduction of cash benefits in the insurance of non-occupational accidents (art. 39 UVG).

Risks are actions by which the insured person exposes himself to a particularly great danger without taking or being able to take precautions to limit the risk to a reasonable extent (art. 50 para. 2 of the Ordinance on Accident Insurance of 20 December 1982 [UVV, SR 832.202]). This covers actions that have a "bold to audacious character" (Erni, p. 25). The focus here is on the element of danger. Accordingly, a risk can also exist if the insured person acts with the greatest care and a high level of expertise (BGE 138 V 522, 528, E. 5.3).

aa. Absolute risk

A distinction is then made between absolute and relative risks. In the case of an absolute risk, either a particularly great danger cannot be reduced to a reasonable level or the action is not worth protecting. According to the case law of the Federal Supreme Court, for example, car-mountain racing, motocross racing or dirt biking are not worth protecting and are therefore considered absolute risks (see Müller, Haftungsfragen, para. 395, with further references). Skiing, mountaineering and climbing are, according to federal court jurisprudence, in principle considered as actions worthy of protection (BGE 104 V 19, 24, E. 2; 97 V 72, 29, E. 3). However, the practice of these sports constitutes an absolute risk if the objective dangers of an alpinistic undertaking are so considerable that they cannot practically be reduced to a reasonable level (cf. Müller, Haftungsfragen, para. 395). For examples, please refer to the individual articles on mountain sports.

bb. Relative risk

In contrast to the absolute risk, the relative risk is linked to the way in which an event is actually carried out. The decisive factor is whether the insured person meets all the requirements (personal abilities, character traits, preparations, etc.) for reducing the risk to a reasonable level (cf. Müller, Haftungsfragen, para. 398). For examples, please refer to the individual articles on mountain sports.

d. Legal consequences

If the insurance company comes to the conclusion that a risk has been taken, this can lead to a half reduction in benefits for life and, in particularly serious cases, to a complete refusal of benefits (art. 50 UVV in conjunction with art. 39 UVG).

Gross negligence leads to a two-year reduction in daily allowances (art. 37 para. 2 UVG). The reduction or denial of benefits is limited to non-occupational accidents in the case of both risk and gross negligence. This is particularly relevant for employed mountain guides, ski instructors, climbing instructors, etc. (cf. Müller, Haftungsfragen, para. 409).

If an action simultaneously constitutes a risk and a culpable causation of damage, the reduction of benefits due to risk takes precedence over that due to gross negligence (Müller, Haftungsfragen, para. 407).

3. Specifically: Rescue costs

The insurance coverage of the rescue costs depends on whether the rescue was due to an accident or illness. For mountain tours planned abroad, it is advisable in any case to take out additional insurance. Furthermore, retired mountain hikers who do not (or no longer) have compulsory accident insurance, but are insured against accidents through a corresponding supplementary policy with their health insurance company, should check their coverage for rescue costs and, if necessary, take out additional insurance to better protect themselves.

a. Rescue due to illness

The compulsory basic insurance covers a contribution to the medically necessary transport costs in the case of rescue due to illness and 50% of the rescue costs in the case of rescue in Switzerland, with a maximum cost ceiling of CHF 5,000 per calendar year (art. 25 Para. 2 lit. g of the Federal Health Insurance Act of 18 March 1994 [KVG, SR 832.10] in conjunction with art. 27 of the EDI Ordinance on Benefits in Compulsory Health Insurance of 18 September 1994 [KLV, SR 832.122.31]). Art. 27 of the Ordinance of the FDHA on Benefits in Compulsory Health Care Insurance of 29 September 1995 [KLV, SR 832.122.31]).

b. Accidental rescue

In the event of an accident-related rescue in Switzerland, the necessary rescue and recovery costs and the medically necessary travel and transport costs will be reimbursed. Further travel and transport costs will be reimbursed if justified by family circumstances. Costs incurred abroad are reimbursed up to a maximum of one fifth of the maximum amount of the insured annual earnings (art. 13 UVG in conjunction with art. 20 UVV).

c. Rescue of a non-injured person

According to the case law of the highest courts (BGE 135 V 88, most recently confirmed by judgment 8C_313/2014 of July 3, 2014), it is not sufficient for costs to be covered under the UVG that there is merely an increased risk to the health of the insured person. The law prescribes the coverage of rescue costs only if a health damage has actually occurred. It also requires that the insured person's body be affected by an extraordinary factor (such as a fall or a rock fall). This is not the case with disorientation or bad weather conditions.

In summary, the Federal Supreme Court concluded in the decision BGE 135 V 88 that a merely objectively dangerous situation from which an insured person is rescued with the help of a helicopter does not constitute an insured event within the meaning of the UVG (BGE 135 V 88, 93, E. 3.3; cf. for a detailed account Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 415 ff.).