Literatur

Bütler, Michael, Zur Haftung von Werkeigentümern und Tierhaltern bei Unfällen auf Wanderwegen, Sicherheit&Recht 2/2009, S. 106 ff; Erni, Franz, Unfall am Berg: wer wagt, verliert!, in: Klett, Barbara (Hrsg.), Haftung am Berg, 2013, S. 15 ff.; Galli, Bernhard, Haftungsprobleme bei alpinen Tourengemeinschaften, Frankfurt a.M. 1995; Hogrefe, Juliane, Mountainbiken, in: Anne Mirjam Schneuwly/Rahel Müller (Hrsg.), Bergsportkommentar ; Hungergühler, Francine, Klettern (inkl. Klettersteige), in: Anne Mirjam Schneuwly/Rahel Müller (Hrsg.), Bergsportkommentar ; Kessler, Martin A., in: Widmer Lüchinger, Corinne/Oser, David (Hrsg.), Basler Kommentar zum Obligationenrecht, Bd. I, 7. Aufl., 2020; Müller, Rahel, Haftungsfragen am Berg, Diss. Bern 2016 (zit. Müller, Haftungsfragen); Müller, Rahel, Die neue Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung – was erwartet uns per 1. Januar 2014?, Sicherheit&Recht 2/2013, S. 94 ff. (zit. Müller, Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung); Niggli, Marcel Alexander/Muskens, Louis Frédéric, in: Niggli, Marcel Alexander/Wiprächtiger, Hans (Hrsg.), Basler Kommentar zum StGB, 4. Aufl 2018, Art. 11 StGB; Nosetti, Pascal, Die Haftung bei geführten Sportangeboten mit erhöhtem Risiko, Diss. Luzern 2012; Oser, David/Weber Rolf H., in: Widmer Lüchinger, Corinne/Oser, David (Hrsg.), Basler Kommentar zum Obligationenrecht, Bd I, 7. Aufl., 2020; Paramalingam, Sridar / Geser, Marcel, Base Jump, in: Anne Mirjam Schneuwly/Rahel Müller (Hrsg.), Bergsportkommentar; Trechsel, Stefan /Jean-Richard, Marc, in: Stefan Trechsel/Mark Pieth (Hrsg.), Schweizerisches Strafrecht, Allgemeiner Teil, Bd. I, 4. Aufl., 2011; Vuille, Miro, Wandern, in: Anne Mirjam Schneuwly/Rahel Müller (Hrsg.), Bergsportkommentar ; Wiegand, Wolfgang, in: Widmer Lüchinger, Corinne/Oser, David (Hrsg.), Basler Kommentar zum Obligationenrecht, Bd I, 7. Aufl., 2020.

Materialien

Botschaft vom 25. Mai 2016 zum Bundesgesetz über das Stabilisierungsprogramm 2017-2019 sowie zum Bundesgesetz über Aufgaben, Organisation und Finanzierung der Eidgenössischen Stiftungsaufsicht, BBl 2016 5691; Stabilisierungsprogramm 2017-2019, Erläuternder Bericht für die Vernehmlassung vom 25. November 2015 (zit. Erläuternder Bericht 2015); Stellungnahme des Bundesrates vom 26. August 2009 zum Bericht vom 27. März 2009 der Kommission für Rechtsfragen des Nationalrates zur Parlamentarischen Initiative 00.431 Rahmengesetz für kommerziell angebotene Risikoaktivitäten und das Bergführerwesen, BBl 2009 6051; Bericht der Kommission für Rechtsfragen des Nationalrats vom 27. März 2009 zur Parlamentarischen Initiative 00.431 Rahmengesetz für kommerziell angebotene Risikoaktivitäten und das Bergführerwesen, BBl 2009 6013; Stellungnahme des Bundesrates vom 14. Februar 2007 zum Bericht vom 1. Dezember 2006 der Kommission für Rechtsfragen des Nationalrates zur Parlamentarischen Initiative 00.431 Rahmengesetz für kommerziell angebotene Risikoaktivitäten und das Bergführerwesen, BBl 2007 1537; Bericht der Kommission für Rechtsfragen des Nationalrats vom 1. Dezember 2006 zur Parlamentarischen Initiative 00.431 Rahmengesetz für kommerziell angebotene Risikoaktivitäten und das Bergführerwesen, BBl 2007 1497.

I. Einführung und Überblick über die Bergsportarten

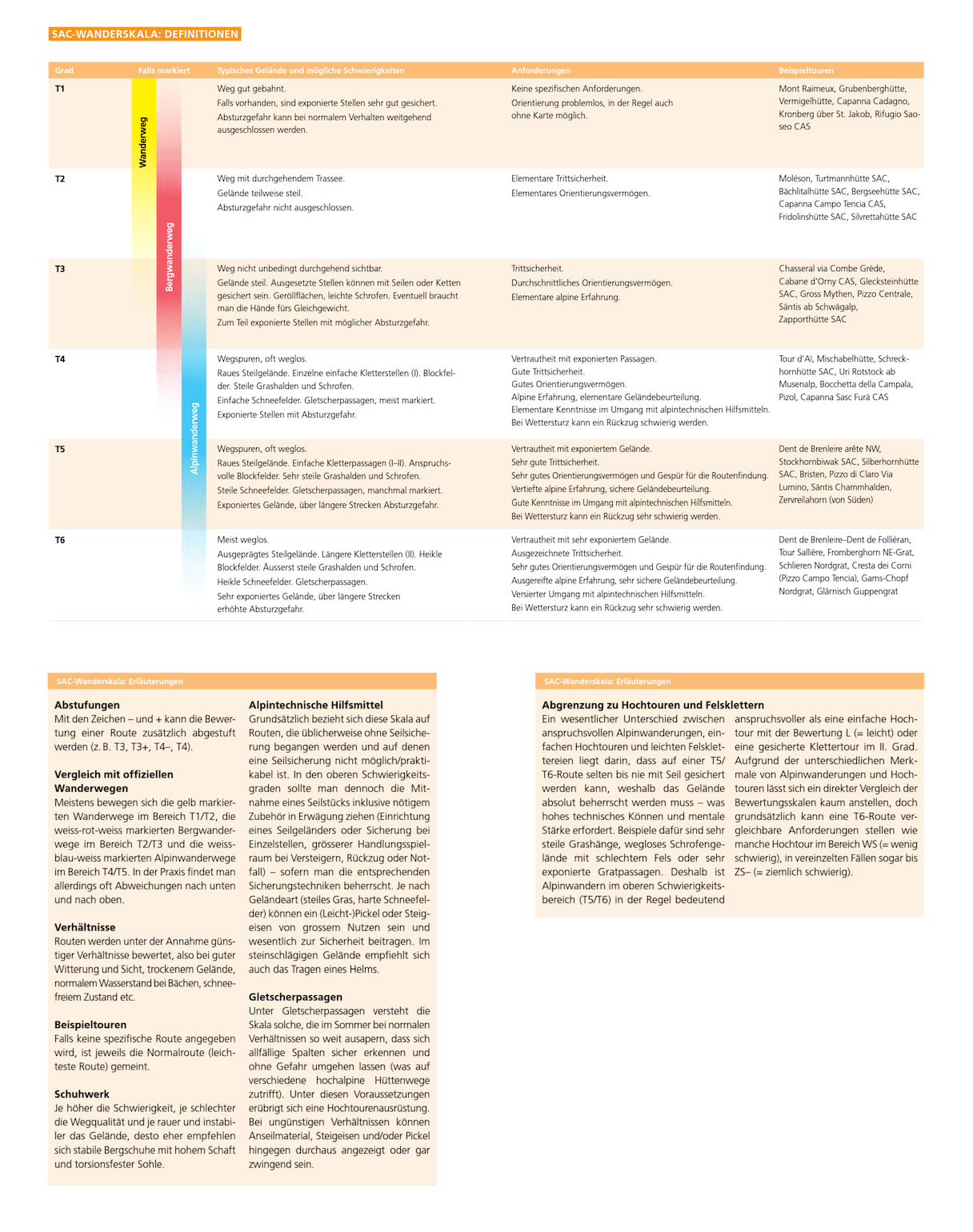

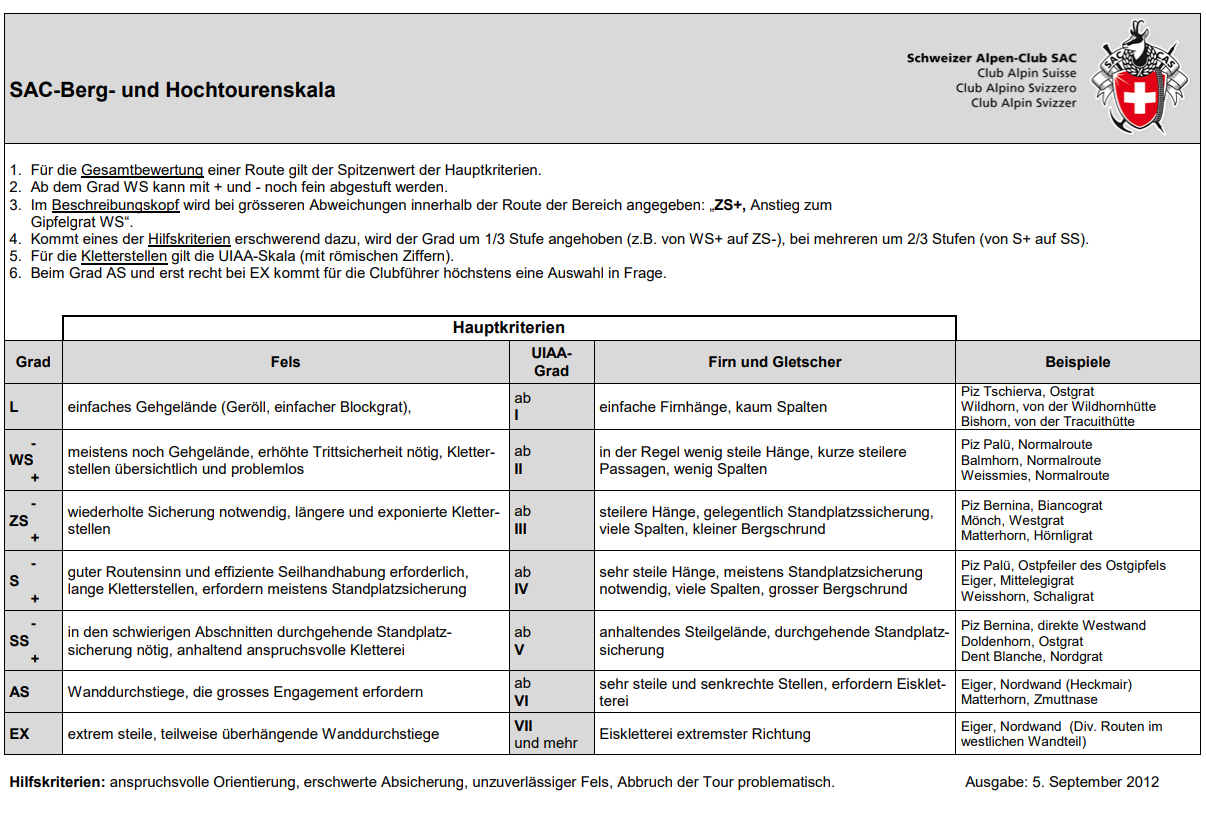

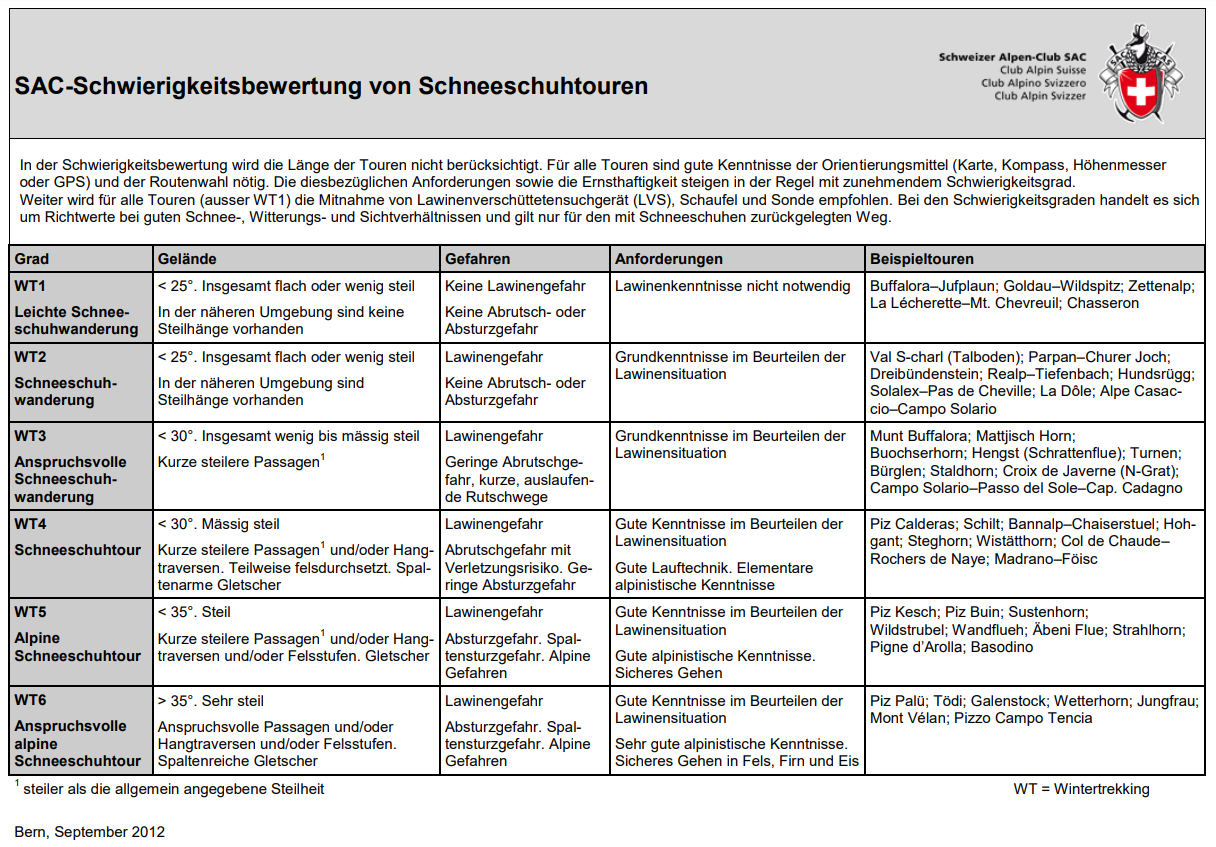

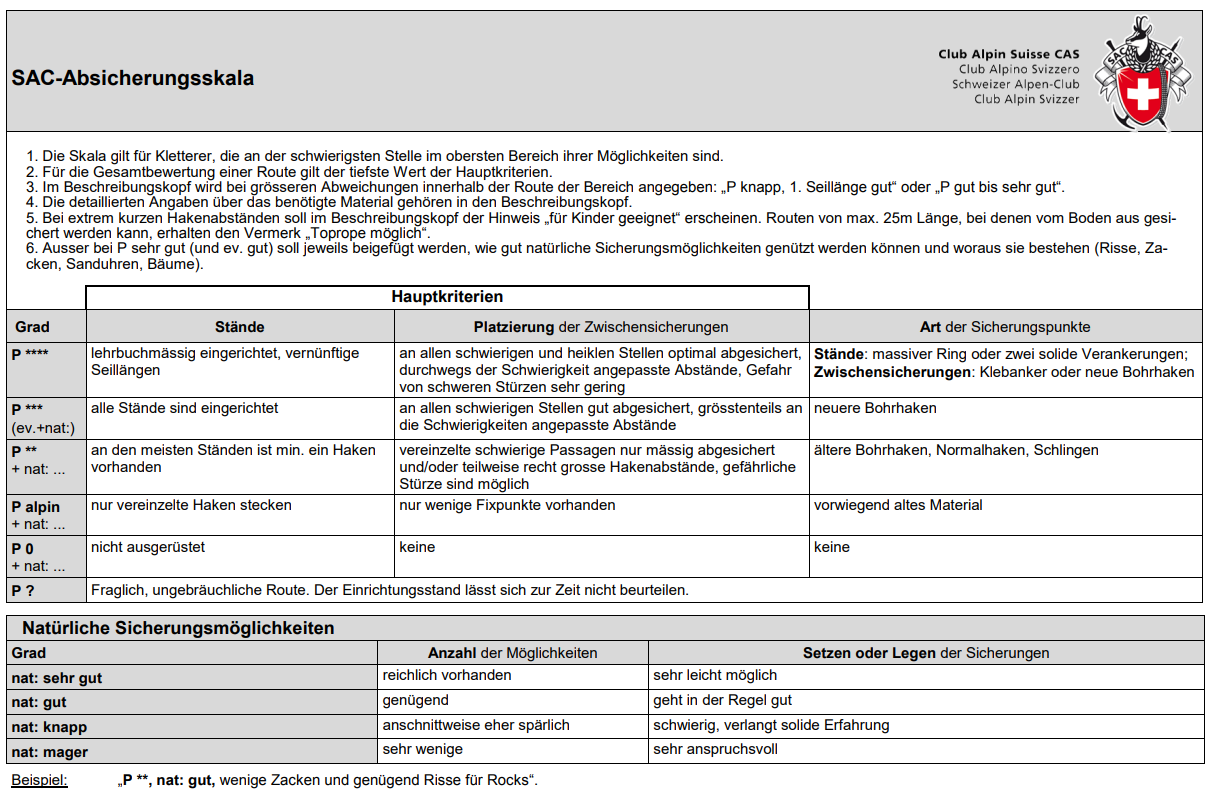

Als Grundlage für den Bergsportkommentar soll eingangs der Begriff Bergsport definiert und ein kurzer Überblick über die Bergsportarten gegeben werden. Alsdann ist auf die Schwierigkeitsskalen des SAC hinzuweisen. Diese ermöglichen Bergsportler*innen nicht nur die Beurteilung, ob eine Aktivität ihren Anliegen, Fähigkeiten und Möglichkeiten entspricht, sondern sie können auch bei der allfälligen rechtlichen Beurteilung eines Bergunfalls von Bedeutung sein. Kommt es zu einem Bergunfall, ist bei der straf- und zivilrechtlichen Beurteilung allfälliger Sorgfaltspflichtverletzungen eine Risikosphärenzuweisung vorzunehmen, um die Eigenverantwortung der Berggänger*innen von der rechtlichen Verantwortung einer Drittperson abzugrenzen. Hierbei kommt den SAC Schwierigkeitsskalen eine tragende Rolle zu: sie definieren auf generell-abstrakter Höhe Anforderungen und schaffen somit die Grundlage für eine rechtliche Beurteilung. Gleich verhält es sich bei einer allfälligen Herabsetzung von Sozialversicherungsansprüchen: bei der Beurteilung einer Handlung (Wagnis, Grobfahrlässigkeit) ist das Unternehmen vorab objektiv einzuordnen – auch hier können die Schwierigkeitsskalen des SAC dienen.

A. Begriff Bergsport

Eine allgemein verbindliche Definition, was unter Berg- oder auch Alpinsport verstanden wird, gibt es nicht. Allgemein sind darunter verschiedenste Aktivitäten, die im Gebirge ausgeübt werden, zu verstehen (siehe auch Galli, S. 7 und Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 12). Bereits ein Blick in die Gliederung des vorliegenden Kommentarwerks zeigt jedoch, dass auch der Anknüpfungspunkt «Gebirge» nicht abschliessend zutrifft: so werden beispielsweise auch Mehrseillängenkletterrouten ausserhalb des Gebirges (vgl. Hungerbühler, Rz. xx), Wanderungen im Flachland (vgl. Vuille, Rz. xx) oder Mountainbiketouren in tiefer gelegenen Wäldern (vgl. Hogrefe, Rz. xx) von diesem Oberbegriff erfasst werden.

Auch die Auflistung im vorliegenden Kommentarwerk ist nicht abschliessend zu verstehen. Unter den Begriff des Bergsports fallen auch Aktivitäten, die im vorliegenden Kommentarwerk (noch) nicht spezifisch behandelt werden.

Auch der Schweizer Alpen-Club SAC hat sich mit der Frage zu befassen, welche Sportarten er unter Bergsport erfassen und entsprechend fördern möchte. So bieten beispielsweise verschiedene SAC-Sektionen Indoor-Kletterkurse an – eine Disziplin, die auf den ersten Blick vielleicht nicht als Bergsportaktivität erfasst wird (vgl. zum Klettern Hungerbühler, passim). Andererseits bietet der Schweizer Alpen-Club gewisse Bergsportaktivitäten (noch) nicht an (z.B. Base Jump – vgl. Paramalingam/Geser, passim).

B. Schwierigkeitsskalen des Schweizer Alpen-Clubs SAC

Der Schweizer Alpen-Club SAC hat für einzelne Bergsportarten Schwierigkeitsskalen herausgegeben (abrufbar unter: https://www.sac-cas.ch/de/ausbildung-und-sicherheit/tourenplanung/schwierigkeitsskalen/). Den Skalen kommt insbesondere im Rahmen der Vorbereitung der Bergsportaktivitäten grosses Gewicht zu, da sie die jeweiligen Anforderungen kurz und zugänglich darstellen. Von Bergsportler*innen wird unter dem Titel der Eigenverantwortung erwartet, vor Antritt einer Bergsportaktivität abzuklären und zu hinterfragen, ob sie einer Aktivität technisch, physisch und psychisch gewachsen sind (siehe auch Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 34).

1. Berg- und Alpinwanderskala

2. Hochtourenskala

3. Schneeschuhtourenskala

4. Absicherungsskala

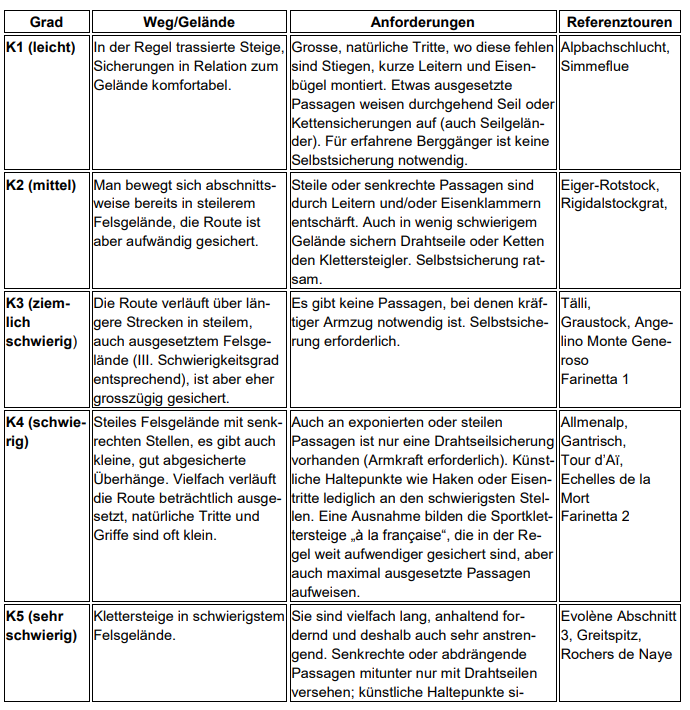

5. Klettersteigskala

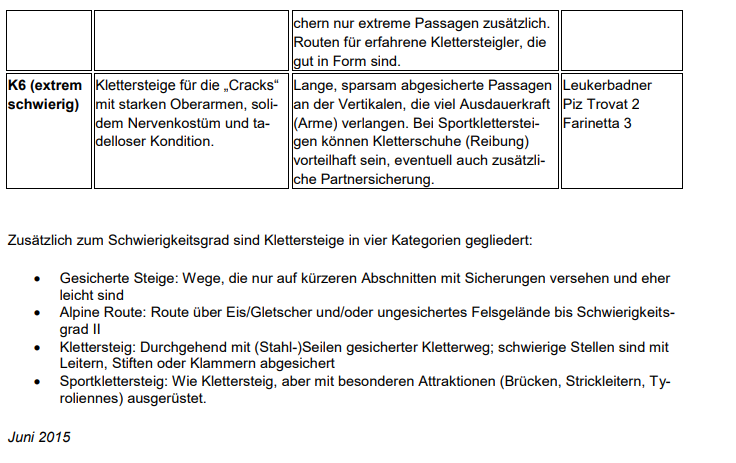

6. Skitourenskala

II. Rechtsgrundlagen

Die Ausübung des Bergsports tangiert verschiedenste Rechtsgebiete: gestartet bei der Frage des Rechts auf «Zutritt» zu den Bergen (Art. 699 ZGB) über verschiedenste Bestimmungen des Umwelt- und Naturschutzes bis hin zu den zivil- und strafrechtlichen Verantwortungsfragen sowie die sozialversicherungsrechtlichen Folgen von Bergunfällen.

Vorliegend werden die Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung, die zivilrechtlichen Haftungsgrundlagen, einige sozialversicherungsrechtliche Grundsätze sowie Denkansätze betreffend die strafrechtliche Beurteilung von Bergunfällen dargestellt. Spezifische Ausführungen finden sich in den Beiträgen zu den einzelnen Bergsportarten.

A. Risikoaktivitätengesetz

1. Ausgangslage

Mittlerweile ist es über 20 Jahre her, seit 21 junge Menschen im Saxetbach, Berner Oberland, bei einem Canyoning-Unfall ihr Leben verloren. Der Unfall führte zu einer Verurteilung von sechs Mitarbeitenden des verantwortlichen Outdoor-Unternehmens wegen fahrlässiger Tötung (Müller, Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung, S. 94). Der Anbieterin wurde strafrechtlich vorgeworfen, keine Risikoanalyse und basierend darauf Sicherheitsmassnahmen getroffen zu haben. Die angeschuldigten Guides wurden hingegen vom Vorwurf der fahrlässigen Tötung freigesprochen. Nur ein Jahr später endete in Stelchelberg ein Bungee-Sprung tödlich – die (gleiche) Anbieterin hat bei einem Bungee-Sprung ein falsches resp. zu langes Seil eingesetzt. Diese Unfälle waren Auslöser einer politischen Diskussion, inwiefern kommerziell angebotene Risikoaktivitäten und das Bergführerwesen reglementiert werden sollen (vgl. auch zusammenfassende Darstellung in BBl 2009 6051 sowie in den weiteren Materialien: BBl 2009 6013, BBl 2007 1537 und BBl 2007 1497).

Am 1. Januar 2014 ist die Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung (Bundesgesetz vom 17. März 2010 über das Bergführerwesen und Anbieten weiterer Risikoaktivitäten RiskG, SR 935.1 und Verordnung über das Bergführerwesen und Anbieten weiterer Risikoaktivitäten vom 30. November 2012, Risikoaktivitätenverordnung [RiskV], SR 935.911) in Kraft getreten. Die Gesetzgebung regelt für Anbieter*innen von so genannten Risikoaktivitäten die Bewilligungs-, Zertifizierungs- und Versicherungspflicht und legt Sorgfaltspflichten fest.

2. Politische Diskussion nach Inkraftsetzung

Knapp zwei Jahre nach Inkrafttreten der Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung hatte der Bundesrat im Rahmen des Stabilisierungsprogramms 2017-2019 die Vernehmlassung zur Aufhebung des RiskG eröffnet. Im erläuternden Bericht hielt der Bundesrat fest, dass die Erfahrungen mit dem Gesetz zeigen würden, dass damit keine zusätzliche Sicherheit geschaffen werde (Erläuternder Bericht 2015, S. 68). Die vorgeschlagene Aufhebung wurde von den Kantonen, Parteien und betroffenen Verbänden mehrheitlich abgelehnt, weshalb der Bundesrat in seiner Botschaft dem Parlament sodann beantragte, auf die Aufhebung des RiskG sei zu verzichten (BBl 2016 4691, S. 4769 und 4770). Bereits diese Entwicklung ist politisch betrachtet aussagekräftig: während die parlamentarische Beratung und Verabschiedung der Gesetzgebung viele Jahre beanspruchte – was Ausdruck dafür ist, dass die Einführung der Regelung kontrovers beurteilt worden ist – war man sich nun mehrheitlich einig, dass eine Aufhebung der Gesetzgebung nicht gewünscht wird.

Vom 28. März bis am 5. Juli 2018 hat der Bundesrat ein Vernehmlassungsverfahren zur Anpassung der RiskV durchgeführt und gestützt auf die daraus gewonnen Erkenntnisse die revidierte Verordnung per 1. Mai 2019 in Kraft gesetzt. Die Totalrevision von 2019 zeigt einerseits die schnelle Entwicklung der verschiedenen Trends der erfassten Sportarten. Andererseits ist sie auch ein Indiz dafür, dass der Gesetzgeber hier Neuland betreten hat und Gesetzgebung und Praxis sich noch in einer Annäherungsphase befinden.

Es bleibt mit Spannung abzuwarten, ob und welche Präzisierungen eine nächste Revision bringen wird.

3. Wichtigste Inhalte im Überblick

a. Geltungsbereich

aa. Anknüpfungspunkt Aktivität

Die Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung führt Kriterien auf, welche eine Aktivität als eine Risikoaktivität qualifizieren. So hält Art. 1 Abs. 1 RiskG fest, dass das gewerbsmässige Anbieten von Risikoaktivitäten in gebirgigem oder felsigem Gelände oder in Bach- oder Flussgebieten, in welchen ein erhöhtes Risiko besteht (namentlich: Absturz- oder Abrutschgefahr oder ein erhöhtes Risiko durch anschwellende Wassermassen, Stein- und Eisschlag oder Lawinen) und zur Begehung besondere Kenntnisse/Sicherheitsvorkehren erforderlich sind, der Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung untersteht (vgl. auch Müller, Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung, S. 95). Art. 3 Abs. 1 RiskG enthält sodann eine abschliessende Aufzählung der erfassten Aktivitäten.

bb. Anknüpfungspunkt Anbieter

Ferner bezeichnet das Gesetz die Tätigkeiten der Bergführer*innen, der Schneesportlehrer*innen ausserhalb des Verantwortungsbereichs von Betreiber*innen von Skilift- und Seilbahnanlagen, Canyoning, River-Rafting, Wildwasserabfahrten sowie Bungee-Jumping als Risikoaktivitäten (Art. 1 Abs. 2 RiskG). Auf Verordnungsstufe werden zudem die Tätigkeiten von Bergführer-Aspirant*innen, Kletterlehrer*innen und Wanderleiter*innen dem Gesetz unterstellt (Art. 1 RiskV).

cc. Gewerbsmässigkeit

Erfasst wird nur das gewerbsmässige Anbieten von Risikoaktivitäten (Art. 1 Abs. 1 RiskG). Wer privat (alleine oder in einer Gruppe) eine Risikoaktivität ausübt, ist von der Gesetzgebung nicht betroffen (vgl. auch Müller, Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung, S. 96). Während der ursprüngliche Verordnungstext (Fassung vom 30. November 2012) für das Kriterium der Gewerbsmässigkeit eine Umsatzgrenze von CHF 2’300 festlegte, hält die seit April 2020 geltende Fassung in Art. 2 Abs. 1 RiskV fest, dass jede Anbieter*in, die auf dem Gebiet der Schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft ein Entgelt erzielt, gewerbsmässig handelt.

Aus den Materialien geht zudem klar hervor, dass Tourenleiter*innen alpiner Vereinigungen vom Geltungsbereich nicht erfasst sind. Bei ihrem Entgelt handelt es sich um eine symbolische Aufwandsentschädigung, die in der Regel nur die Spesen deckt (BBl 2009 6013, S. 6029). Konkret bedeutet dies, dass SAC-Touren nicht unter die Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung fallen.

b. Sorgfaltspflichten

Anbieter*innen von Risikoaktivitäten müssen nach der Generalklausel von Art. 2 Abs. 1 RiskG «die Massnahmen treffen, die nach der Erfahrung erforderlich, nach dem Stand der Technik möglich und nach den gegebenen Verhältnissen angemessen sind, damit Leben und Gesundheit der Teilnehmer und Teilnehmerinnen nicht gefährdet werden». Diese Formulierung orientiert sich am allgemeinen Gefahrensatz, welcher denjenigen, der einen Zustand schafft oder aufrechterhält, der einen anderen schädigen könnte, dazu verpflichtet, die zur Vermeidung eines Schadens erforderlichen Vorsichtsmassnahmen zu treffen (Bütler, S. 112; Müller, Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung, S. 97).

Art. 2 Abs. 2 RiskG enthält sodann einen nicht abschliessenden Pflichtenkatalog: Teilnehmer*innen von Risikoaktivitäten sind über besondere Gefahren aufzuklären (lit. a) und es ist zu überprüfen, ob sie über ein ausreichendes Leistungsvermögen verfügen, um die gewählte Aktivität auszuüben (lit. b). Die Mängelfreiheit des Materials und allfälliger Installationen ist sicherzustellen (lit. c). Die Eignung der Wetter- und Schneebedingungen ist zu überprüfen (lit. d) und die Qualifizierung des Personals ist sicherzustellen (lit. e). Es ist zudem sicherzustellen, dass entsprechend dem Schwierigkeitsgrad und der Gefahr genügend Begleitpersonen vorhanden sind (lit. f). Schliesslich ist Rücksicht auf die Umwelt zu nehmen und die Lebensräume von Tieren und Pflanzen sind zu schonen (lit. g).

Die Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung schafft keinen zivilrechtlichen Haftungstatbestand, sondern definiert Sorgfaltspflichten, deren Verletzung haftungsbegründend sein kann (Müller, Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung, S. 98; Nosetti, Rz. 1184). Ferner gehen gemäss der vorliegend vertretenen Meinung die in der Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung festgelegten Sorgfaltspflichten nicht weiter als jene, die sich bereits aus dem allgemeinen Auftragsrecht ergeben.

c. Bewilligungspflicht

Die Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung statuiert für das gewerbsmässige Anbieten von Risikoaktivitäten eine Bewilligungspflicht (Art. 3 RiskG).

aa. Bewilligung für Bergführer*innen

Bergführer*innen erhalten eine Bewilligung, wenn sie über einen eidgenössischen Fachausweis (Art. 43 des Berufsbildungsgesetzes vom 13. Dezember 2002; BBG, SR 412.10) oder über einen gleichwertigen in- oder ausländischen Fähigkeitsausweis verfügen, sie Gewähr für die Einhaltung der Pflichten nach dem RiskG bieten und eine Berufshaftpflichtversicherung abgeschlossen haben (Art. 4 Abs. 1 und Art. 13 RiskG).

Bergführer*innen mit entsprechender Bewilligung sind sodann zum Anbieten folgender Aktivitäten ermächtigt (Art. 4 Abs. 1 RiskV i.V.m. Art. 3 Abs. 1 lit. a-h RiskV):

- Hochtouren

- Alpinwandern

- Touren mit Skis, Snowboards und ähnlichen Schneesportgeräten

- Schneeschuhtouren

- Variantenabfahrten

- Begehen von Klettersteigen

- Eisfall- und Steileisklettern

- Klettern

- Canyoning, sofern die Bergführer*in über eine Zusatzausbildung des Schweizer Bergführerverbands (SBV) oder über ein durch die IVBV anerkanntes Diplom verfügt

Die Bewilligung für Bergführer-Aspirant*innen berechtigt zur Ausübung der soeben aufgeführten Tätigkeiten, sofern dies unter der direkten oder indirekten Aufsicht und der Mitverantwortung einer/eines Bergführer*in mit einer Bewilligung geschieht (Art. 5 RiskV).

bb. Bewilligung für Schneesportlehrer*innen

Schneesportlehrer*innen erhalten eine Bewilligung für das Führen von Kund*innen ausserhalb des Verantwortungsbereichs von Betreiber*innen von Skilift- und Seilbahnanlagen, wenn sie über einen eidgenössischen Fachausweis (Art. 43 BBG) oder über einen gleichwertigen in- oder ausländischen Fähigkeitsausweis verfügen, sie Gewähr für die Einhaltung der Pflichten nach dem RiskG bieten und eine Berufshaftpflichtversicherung abgeschlossen haben (Art. 5 und Art. 13 RiskG).

Schneesportlehrer*innen mit entsprechender Bewilligung sind sodann zum Anbieten folgender Aktivitäten ermächtigt (Art. 7 RiskV):

- Touren mit Skis und Snowboards bis max. Schwierigkeitsgrad WS

- Schneeschuhtouren bis max. Schwierigkeitsgrad WT3

- Variantenabfahrten bis max. Schwierigkeitsgrad S (Neuerung seit 2019 – davor ZS), sofern keine Absturzgefahr besteht.

Sämtliche Aktivitäten dürfen jedoch nur angeboten werden, sofern bei der konkreten Aktivität

- keine Gletscher überquert werden, und

- abgesehen von Scheesportgeräten, Fellen, Harscheisen und Schneeschuhen keine weiteren technischen Hilfsmittel wie Pickel, Steigeisen oder Seile verwendet werden müssen, um die Sicherheit der Kund*innen zu gewährleisten.

cc. Bewilligung für Kletterlehrer*innen

Kletterlehrer*innen erhalten eine Bewilligung für das Klettern mit mehr als einer Seillänge mit Kund*innen (vgl. Hungerbühler, Rz. xx), wenn sie über einen eidgenössischen Fachausweis (Art. 43 BBG) oder über einen gleichwertigen in- oder ausländischen Fähigkeitsausweis verfügen, sie Gewähr für die Einhaltung der Pflichten nach dem RiskG bieten und eine Berufshaftpflichtversicherung abgeschlossen haben (Art. 6 und Art. 13 RiskG, Art. 6 RiskV).

Der Zu- resp. Abstieg zur Kletterstelle darf hierbei (Art. 6 Abs. 1 RiskV):

- kein Gehen am kurzen Seil erfordern (eine allfällige Sicherung der Kund*in von einem gesicherten Standplatz aus ist hingegen zulässig);

- keine Überquerung von Gletschern erfordern und

- keine Verwendung von technischen Hilfsmitteln wie Pickel oder Steigeisen erfordern.

Das Klettern mit Kund*innen über eine Seillänge untersteht nicht der Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung und kann somit frei – auch gewerbsmässig – angeboten werden (Art. 3 Abs. 1 lit. h RiskV e contrario). Gemäss Sinn und Zweck der Gesetzgebung müssen hierbei die Anforderungen an den Zu-/Abstieg (Art. 6 Abs. 1 RiskV) jedoch ebenfalls eingehalten werden. Je nach Ausgestaltung des Zu-/Abstieges zu einer Kletterpassage hat diese somit unter der Verantwortung einer/eines Bergführer*in zu erfolgen, falls ein gewerbsmässiges Angebot vorliegt.

Für das Begehen von Klettersteigen mit Kund*innen (Art. 3 Abs. 1 lit. f RiskV) ist der Abschluss einer Zusatzausbildung erforderlich (Art. 6 Abs. 4 RiskV). Kletterlehrer*innen in Ausbildung dürfen sodann unter direkter Aufsicht und Verantwortung einer Person mit einer Bewilligung Klettertouren mit mehr als einer Seillänge durchführen, sofern dies für die Ausbildung erforderlich ist (Art. 6 Abs. 5 RiskV).

dd. Bewilligung für Wanderleiter*innen

Das Anbieten von Wanderungen bis zum Schwierigkeitsgrad T3 (Wandern und Bergwandern) fällt nicht unter die Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung (Art. 3 Abs. 1 lit. b e contrario) und kann somit – gewerbsmässig – bewilligungsfrei, auch durch Personen, die nicht Wanderleiter*innen sind, angeboten warden (vgl. auch Vuille, Rz. xx).

Wanderleiter*innen erhalten eine Bewilligung für das Begleiten von Kund*innen bei Alpinwanderungen mit dem Schwierigkeitsgrad T4 sowie bei Schneeschuhtouren mit dem maximalen Schwierigkeitsgrad WT3, wenn sie über einen eidgenössischen Fachausweis (Art. 43 BBG) oder über einen gleichwertigen in- oder ausländischen Fähigkeitsausweis verfügen, sie Gewähr für die Einhaltung der Pflichten nach dem RiskG bieten und eine Berufshaftpflichtversicherung abgeschlossen haben (Art. 6 und Art. 13 RiskG, Art. 8 RiskV).

Für Schneeschuhtouren gelten die Einschränkungen (Art. 8 Abs. 1 RiskV), dass keine Gletscher überquert werden und abgesehen von Schneeschuhen keine technischen Hilfsmittel wie Pickel, Steigeisen oder Seile verwendet werden müssen, um die Sicherheit der Kund*innen zu gewährleisten. Für das Anbieten von Alpinwanderungen (T4) ist ferner eine Zusatzausbildung erforderlich, welche den Bereich Sicherheit und Risikomanagement beim Alpinwandern abdeckt. Wanderleiter*innen in Ausbildung dürfen sodann unter direkter Aufsicht und Verantwortung einer Person mit einer Bewilligung die genannten Aktivitäten durchführen, sofern dies für die Ausbildung erforderlich ist (Art. 6 Abs. 5 RiskV).

An dieser Stelle sei ein Fragezeichen betreffend die Einschränkung der Mitnahme eines Seils erlaubt: Bedenkt man einerseits, dass das gewerbsmässige Anbieten von Einseillängenkletterrouten nicht der Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung unterliegt und andererseits, dass es im Interesse aller Beteiligter liegen kann, dass an einer Schlüsselstelle mittels Seil abgesichert wird, erscheint die Einschränkung von Art. 8 Abs. 1 lit. c RiskV (sowie Art. 8 Abs. 4 lit. c i.V.m. Art. 8 Abs. 1 lit. c RiskV) als wenig praxisorientiert und zu streng. Es ist überzeugend, dass das Gehen am kurzen Seil (sofern gewerbsmässig angeboten) den Bergführer*innen vorbehalten bleibt. Ein Absichern von einem Stand aus sollte jedoch gemäss der hier vertretenen Auffassung unter Vorliegen der erforderlichen Zusatzausbildung (Art. 8 Abs. 4 lit. b RiskV) auch Wanderleiter*innen möglich sein, um möglichst risikominimierte T4 Touren anbieten zu können.

ee. Bewilligung für übrige Anbieter*innen von Risikoaktivitäten

Artikel 9 RikV regelt sodann die Bewilligung für Leiter*innen von Wildwasserfahrten. Für die übrigen Anbieter*innen von Risikoaktivitäten wird für die Durchführung der entsprechenden Aktivität eine Zertifizierung vorausgesetzt (Art. 10 RiskV). Auch diese Anbieter*innen müssen Gewähr für die Einhaltung der Pflichten nach dem RiskG bieten und eine Berufshaftpflichtversicherung abgeschlossen haben (Art. 6 und Art. 13 RiskG).

B. Haftungsgrundlagen

1. Einleitende Bemerkungen

Zivilrechtlich wird zwischen Anbieter*innen von Bergsportaktivitäten und Bergsportler*innen zumeist ein auftragsrechtliches Verhältnis nach Art. 394 ff. OR vorliegen.

Die Auftragnehmer*innen haften gegenüber den Auftraggeber*innen, wenn Letztere durch unsorgfältige oder treuwidrige Besorgung des übertragenen Geschäfts geschädigt werden (Art. 398 Abs. 2 OR). Führt ein sorgfaltswidriges Verhalten der Auftragsnehmer*in zu einer Körperverletzung oder zum Tod einer Auftraggeber*in, kann dies im Einzelfall zu Schadenersatz- und/oder Genugtuungsansprüchen der verletzten Person resp. der Hinterbliebenen führen (Art. 398 Abs. 2 i.V.m. Art. 97 Abs. 1 OR; Art. 99 Abs. 3 i.V.m. Art. 47 OR).

Daneben steht in Anspruchskonkurrenz die Haftung aus unerlaubter Handlung (Art. 41 Abs. 1 OR).

Keine Haftungsgrundlage bildet hingegen die Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung.

2. Eigenverantwortung am Berg

Führt ein Bergunfall zu einem haftpflichtrechtlich relevanten Schaden (siehe nachfolgend Rz. xx), kann dieser nur auf Dritte überwälzt werden, falls und insofern keine eigenverantwortliche Schädigung vorliegt. Konkret geht es um eine Risikosphärenabgrenzung: Zieht eine Person zur Durchführung einer Bergsportaktivität einen Profi – beispielsweise eine Bergführer*in – hinzu, wird ein Teil der Eigenverantwortung auf die Führerperson übertragen. Das alpine Restrisiko verbleibt aber auch diesfalls bei der geführten Person. Beispiele für das alpine Restrisiko sind Stein-/Felsausbrüche oder Stolperstürze auf Gelände, auf welchem nicht zu sichern war oder auch ex ante nicht vorhersehbare Lawinenabgänge (Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 31 ff., m.w.H.).

Zur Eigenverantwortung gehört die Pflicht der Alpinist*innen, die Tätigkeit entsprechend ihrer Fähigkeiten auszuüben, die notwendigen Vorabklärungen bezüglich Schwierigkeitsgrade zu treffen und sich genügend auszurüsten. Auch der Abbruch einer Tour ist Bestandteil des eigenverantwortlichen Handelns (Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 34).

Der Grundsatz der Eigenverantwortung findet bei sämtlich denkbaren Haftungskonstellationen Anwendung und ist auch bei der strafrechtlichen Beurteilung zu berücksichtigen (Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 28 und 33).

3. Insbesondere: Schaden

Der Schaden bemisst sich nach der Differenztheorie: Der aktuelle Vermögensstand der geschädigten Person wird mit dem hypothetischen Vermögensstand bei Ausbleiben des schädigenden Ereignisses verglichen (statt vieler BSK-Kessler, Art. 41 OR N 3).

Bei Bergunfällen sind insbesondere folgende Schadensarten relevant (vgl. Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 49, m.w.H.):

- Personenschaden: Rettungs- und Transportkosten, Arzt- und Pflegekosten, Verdienstausfall, Bergungs- und Bestattungskosten sowie der Versorgerschaden;

- Sachschaden: Wert des mitgeführten Materials;

- Frustrationsschaden: z.B. Anspruch auf Ersatz von bereits bezahltem Aufwand, wie Anreisekosten, bereits bezahlte Hüttenübernachtung oder Bergführer*innenkosten. Gemäss herrschender Lehre und Rechtsprechung wird der Frustrationsschaden nicht ersetzt.

4. Vertragshaftung

Bei einer gewerbsmässig angebotenen Tour – aber auch bei SAC-Touren – besteht zwischen der Anbieterin und dem Gast ein Vertragsverhältnis. Die Haftung richtet sich nach Art. 398 Abs. 2 i.V.m. Art. 97 Abs. 1 OR. Vorausgesetzt werden ein Schaden (vgl. oben Rz. xx), ein Kausalzusammenhang zwischen dem schädigenden Verhalten und dem eingetretenen Schaden sowie ein Verschulden. Letzteres wird bei der Vertragshaftung aber grundsätzlich vermutet (statt vieler BSK-Wiegand, Art. 97 OR N 42). Die Anbieterin hat sich sodann das allfällige Fehlverhalten der führenden Person unter dem Titel der Hilfspersonenhaftung anrechnen zu lassen (Art. 101 OR).

Bei Bergunfällen kommt der Frage des Verschuldens und somit der Sorgfaltspflichtverletzung eine zentrale Rolle zu. Wie dargelegt, normiert die Risikoaktivitätengesetzgebung gewisse Sorgfaltspflichten (vgl. oben Rz. xx). Die aus dem Auftragsrecht geschuldete Sorgfalt bestimmt sich sodann im konkreten Einzelfall und ist somit auch von der Erfahrung der geführten Person abhängig. Verlangt wird von der Führerperson jene Sorgfalt, welche eine gewissenhafte beauftragte Person in der gleichen Lage unter Berücksichtigung des spezifischen Vertragsinhalts bei der Besorgung der ihr übertragenen Geschäfte anwendet (BSK-Oser/Weber, Art. 398 OR N 24). Für die konkreten Sorgfaltspflichten von hinzugezogenen Führerpersonen wird auf die Beiträge im BT verwiesen. Hierbei gilt immer zu beachten, dass die Eigenverantwortung der Gäste durch den Beizug einer Führerperson nicht gegenstandslos wird (Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 302).

5. Haftung aus Delikt

Die Deliktshaftung (Verschuldenshaftung, Art. 41 OR) verlangt wie die Vertragshaftung neben dem Vorliegen eines kausal verursachten Schadens (vgl. oben Rz. xx) Widerrechtlichkeit sowie ein Verschulden. Die Beweislast für das Vorliegen der Haftungsvoraussetzungen liegt hierbei bei der geschädigten Person.

Betreffend das Verschulden (Sorgfaltspflichtverletzung) kann auf die Ausführungen zur Vertragshaftung verwiesen werden.

6. Werkeigentümerhaftung

Während die Deliktshaftung ein Verschulden voraussetzt, bietet Art. 58 OR die Möglichkeit, Eigentümer*innen eines Gebäudes oder eines anderen Werkes für den Schaden, den dieses infolge von fehlerhaften Anlage oder Herstellung oder von mangelhafter Unterhaltung verursacht, verschuldensunabhängig zu belangen (Kausalhaftung). Dies könnte bei Wanderunfällen relevant sein: Gemäss Lehre und Rechtsprechung kommt Wanderwegen dann Werkcharakter zu, wenn der Weg durch erhebliche Abtragungen, Sprengungen und Aufschüttungen künstlich angelegt oder mit baulichen Konstruktionen oder Sicherungselementen versehen wurde (vgl. Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 75 ff., m.w.H.; Vuille, Rz. xx). Aber auch bei Kletterunfällen kann eine Werkeigentümerhaftung zum Tragen kommen (vgl. Hungerbühler, Rz. xx)

7. Weitere Haftungsgrundlagen

Neben der Vertragshaftung und der Deliktshaftung kommen im Einzelfall auch weitere Haftungsgrundlagen in Frage. Zu Denken ist beispielsweise an eine allfällige Vertrauenshaftung (vgl. Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 104).

Ein Spezialfall stellt schliesslich die von Tieren ausgehende Gefahr dar, wie beispielsweise durch Herdenschutzhunde, Mutterkühe oder Stiere (Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 49). Relevant ist hierbei die Tierhalterhaftpflicht nach Art. 56 OR (Vgl. zum Ganzen Vuille, Rz. xx.).

C. Strafrecht

1. Massgebende Delikte

In strafrechtlicher Hinsicht sind bei Bergunfällen insbesondere die Bestimmungen der fahrlässigen Tötung (Art. 117 StGB) und der fahrlässigen Körperverletzung (Art. 125 StGB) einschlägig.

2. Insbesondere: Pflichtwidrige Unvorsichtigkeit

Die fahrlässige Begehung eines Verbrechens oder Vergehens setzt eine pflichtwidrige Unvorsichtigkeit voraus. Eine solche liegt vor, wenn eine Täter*in die Vorsicht nicht beachtet, zu der sie oder er nach den Umständen und nach ihren resp. seinen persönlichen Verhältnissen verpflichtet ist (Art. 12 Abs. 3 StGB).

Gemäss bundesgerichtlicher Rechtsprechung handelt sorgfaltswidrig, wer zum Zeitpunkt der Tat aufgrund der Umstände sowie Kenntnisse und Fähigkeiten die damit bewirkte Gefährdung der Rechtsgüter des Opfers hätte erkennen können und müssen und zugleich die Grenzen des erlaubten Risikos überschritten hat. Das Mass der zu erbringenden Sorgfalt richtet sich, wo besondere, der Unfallverhütung und der Sicherheit dienende Normen ein bestimmtes Verhalten gebieten, in erster Linie nach diesen Vorschriften. Fehlen solche, kann auf analoge Regeln (halb-)privater Vereinigungen abgestellt werden, sofern diese allgemein anerkannt sind. Der Vorwurf der Fahrlässigkeit lässt sich aber auch auf allgemeine Rechtsgrundsätze wie den Gefahrensatz abstützen. Die Zurechenbarkeit des Erfolgs bedingt die Vorhersehbarkeit nach dem Massstab der Adäquanz. Weiter wird vorausgesetzt, dass der Erfolg vermeidbar war. Unter dem hypothetischen Kausalverlauf wird geprüft, ob der Erfolg bei pflichtgemässem Verhalten der Täter*in ausgeblieben wäre. Für die Zurechnung des Erfolgs genügt, wenn das Verhalten der Täter*in mindestens mit einem hohen Grad an Wahrscheinlichkeit die Ursache des Erfolgs bildet (BGer 6B_535/2019 vom 13. November 2019, E. 1.3.1; BGE 135 IV 56, E. 2.1., m.H.; BGer 6B_351/2017 vom 1. März 2018, E.1.3.1).

Grundsätzlich entspricht bei Bergunfällen die strafrechtliche relevante pflichtwidrige Unvorsichtigkeit der zivilrechtlich geschuldeten und bei deren Verletzung haftungsrelevanten Sorgfaltspflicht (vgl. jedoch die Ausführungen zu Art. 53 OR nachfolgend unter Ziffer 4).

3. Begehung durch Unterlassung

Bei Bergunfällen wird regelmässig ein Begehen durch Unterlassung geprüft. Dies ist insofern naheliegend, als in jedem Fahrlässigkeitsvorwurf eine Unterlassung liegt, nämlich die Nichtbeachtung einer Sorgfaltspflicht (Trechsel/Jean-Richard, § 17 N 1).

Unterlässt beispielsweise ein Pistenchef (pflichtwidrig) die Sperrung eines Skigebiets trotz erhöhter Lawinengefahr und verschüttet sodann eine Lawine die Piste, kann dies zu einer Verurteilung wegen fahrlässiger Tötung durch Unterlassung führen (BGE 138 IV 124). Auch der Direktor einer Seilbahn, der es unterlässt, den Betrieb trotz Kenntnis eines technischen Problems zu unterbrechen, macht sich unter Umständen der fahrlässigen Tötung durch Unterlassen strafbar, falls sodann bei einem Unfall eine Person ums Leben kommt (BGE 122 IV 61). Ein anderer – in der Lehre häufig zitierter – Fall betrifft den Ehemann, der seine wenig berggewohnte und im Skifahren ungeübte Ehefrau trotz schlechtem Wetter mit auf eine Skitour nimmt, hierbei nicht die kürzeste und leichteste Route wählt, beim Wetterumsturz nicht umkehrt, die Nacht in Schnee und Eis verbringt ohne Massnahmen zu treffen, um seine Frau gegen die Kälte zu schützen und diese schliesslich in den Morgenstunden verlässt (woraufhin diese verstirbt). Auch hier wurde eine fahrlässige Tötung durch Unterlassung bejaht (BGE 83 IV 9).

Gemäss herrschender Lehre und Rechtsprechung gilt in der Schweiz jedoch die Subsidiaritätstheorie: Ein Vorwurf ist primär als Handlung zu verstehen, solange ein rechtlich kausales Handeln vorliegt (BSK-Niggli/Muskens, Art. 11 StGB N 53). Beim Begehungsdelikt besteht der Vorwurf darin, durch eine Handlung einen Erfolg bewirkt zu haben, beim Unterlassungsdelikt darin, den Erfolg durch aktives Tun nicht abgewendet zu haben (BSK-Niggli/Muskens, Art. 11 StGB N 52). In der Praxis gestaltet sich die Abgrenzung oftmals schwierig. Das Obergericht des Kantons Bern hatte sich mit folgendem Sachverhalt befasst: Ein Bergführer hat es unterlassen, zwei ihm anvertraute Mädchen beim Zustieg zu einer Abseilstelle mittels Seil zu sichern. Es kam zu einem tödlichen Sturz eines der Mädchen. Das Obergericht hat festgehalten, es handle sich hierbei nicht um eine Unterlassung. Dem Bergführer sei vielmehr ein Tun vorzuwerfen: Nämlich das Führen ohne Seilsicherung (Urteil des Obergerichts des Kantons Bern vom 25. Januar 2019, SK 18 12, N 16). Im Ergebnis wurde der besagte Bergführer (nach der hier vertretenen Auffassung in zutreffender Weise) freigesprochen, da sich der Bergführer bei seinem Vorgehen «im Bereich des erlaubten Risikos» bewegte.

Unterlassungsdelikte setzen das Vorliegen einer qualifizierten Rechtspflicht (Garantenstellung) voraus (BSK-Niggli/Muskens, Art. 11 StGB N 6). Führende Personen (wie Bergführer*innen, Tourenleiter*innen, Wanderleiter*innen, Kletterlehrer*innen) aber auch faktische Führerpersonen wird regelmässig eine Garantenstellung treffen.

4. Zivil- und Strafverfahren

Da ein zivilrechtlich relevantes pflichtwidriges Verhalten anlässlich einer Bergsportaktivität regelmässig auch strafrechtlich relevant ist resp. sein könnte, wird eine geschädigte Person oftmals sowohl die Einleitung zivilrechtlicher als auch strafrechtlicher Schritte prüfen.

Zu beachten ist hierbei Art. 53 Art. 1 OR, welcher besagt, dass der Zivilrichter insbesondere bei der Beurteilung der Schuld oder Nichtschuld nicht an eine Freisprechung durch das Strafgericht gebunden ist. Ebenso ist die strafgerichtliche Erkenntnis mit Beurteilung der Schuld und die Bestimmung des Schadens für den Zivilrichter nicht verbindlich (Art. 53 Abs. 2 OR). Diese Bestimmung kommt nicht zur Anwendung, wenn die geschädigte Person unter den Opferbegriff von Art. 1 des Bundesgesetzes über die Hilfe an Opfer von Straftaten vom 23. März 2007 (OHG, SR 312.5) fällt und über den Zivilpunkt entweder adhäsionsweise in einem Strafverfahren entschieden wird oder ein Zivilgericht die Höhe des Zivilanspruchs zu bestimmen hat, nachdem ein Strafrichter im Grundsatz über den Zivilpunkt geurteilt hat (BSK-Kessler, Art. 53 OR N 2a).

Für weitergehende verfahrensrechtliche Fragestellungen wird auf den Beitrag von Müller/ Sidiropoulos verwiesen.

D. Sozialversicherungsrecht

1. Einleitende Bemerkungen

Arbeitnehmer*innen (inkl. Auszubildende) der Schweiz sind zum Abschluss einer Unfallversicherung inkl. Nichtbetriebsunfälle verpflichtet (Art. 1a Abs. 1 und Art. 6 Abs. 1 des Bundesgesetzes über die Unfallversicherung vom 20. März 1981 [UVG, SR 832.20]).

Versicherungsrechtlich wird unter Unfall «die plötzliche, nicht beabsichtigte schädigende Einwirkung eines ungewöhnlichen, äusseren Faktors auf den menschlichen Körper, die eine Beeinträchtigung der körperlichen, geistigen oder psychischen Gesundheit oder den Tod zur Folge hat», verstanden (Art. 4 des Bundesgesetzes über den Allgemeinen Teil des Sozialversicherungsrechts vom 6. Oktober 2000 [ATSG, SR 830.1]). Typische haftungsrelevante Bergunfälle, wie beispielsweise ein Absturz, werden zumeist klar als Unfall zu qualifizieren sein (Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 385).

2. Leistungskürzungen /-verweigerungen

a. Grundlagen

Die schuldhafte – namentlich grobfahrlässige – Schadensherbeiführung (Art. 37 UVG) und das Eingehen einer aussergewöhnlichen Gefahr oder eines Wagnisses (Art. 39 UVG) kann zu Leistungskürzungen oder gar -verweigerungen führen.

Begründet wird diese Regelung damit, dass den Prämienzahler*innen nicht zu grosse finanzielle Lasten aufgebürdet werden sollen, wenn sich versicherte Personen aussergewöhnlichen Risiken aussetzen und dabei verunfallen (vgl. Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 388).

Für Bergsportler*innen macht – je nach Bergsportart sowie Art und Weise der Ausübung der entsprechenden Bergsportart – der Abschluss einer speziellen privatrechtlichen Versicherung Sinn, um im Schadensfall eine genügende Versicherungsdeckung – gerade auch für die hinterbliebenen Personen – sicherzustellen.

b. Grobfahrlässige Herbeiführung

Gemäss bundesgerichtlicher Rechtsprechung wird unter dem grobfahrlässigen Handeln die Missachtung der elementaren Vorsichtsgebote, die jeder verständige Mensch in der gleichen Lage und unter den gleichen Umständen befolgt hätte, um eine nach dem natürlichen Lauf der Dinge voraussehbare Schädigung zu vermeiden, verstanden (BGE 138 V 522, 527, E. 5.2.1; 121 V 40, 45, E. 3b; 118 V 305, 306, E. 2). Massgebend sind hierbei die konkreten Verhältnisse des Einzelfalls. Für Beispiele wird auf die einzelnen Beiträge zu den Bergsportarten verwiesen.

c. Wagnis

Der Bundesrat kann aussergewöhnliche Gefahren und Wagnisse bezeichnen, die in der Versicherung der Nichtberufsunfälle zur Verweigerung sämtlicher Leistungen oder zur Kürzung der Geldleistungen führen (Art. 39 UVG).

Wagnisse sind Handlungen, mit denen sich die versicherte Person einer besonders grossen Gefahr aussetzt, ohne die Vorkehren zu treffen oder treffen zu können, die das Risiko auf ein vernünftiges Mass beschränken (Art. 50 Abs. 2 der Verordnung über die Unfallversicherung vom 20. Dezember 1982 [UVV, SR 832.202]). Erfasst werden Handlungen, die einen «ins Kühne bis Verwegene gehenden Charakter» (Erni, S. 25) aufweisen. Im Vordergrund steht hierbei das Gefahrenmoment. Entsprechend kann ein Wagnis auch vorliegen, wenn die versicherte Person mit grösster Sorgfalt und hohem Sachverstand handelt (BGE 138 V 522, 528, E. 5.3).

aa. Absolutes Wagnis

Es wird sodann unterschieden zwischen absoluten und relativen Wagnissen. Bei einem absoluten Wagnis kann entweder eine besonders grosse Gefahr gar nicht auf ein vernünftiges Mass reduziert werden oder die Handlung ist nicht schützenswert. Gemäss Rechtsprechung des Bundesgerichts gelten beispielsweise Auto-Bergrennen, Motocross-Rennen oder das Dirt-Biken als nicht schützenswert und somit als absolute Wagnisse (vgl. zum Ganzen Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 395, m.w.H.). Skifahren, Bergsteigen und Klettern gelten gemäss bundesgerichtlicher Rechtsprechung grundsätzlich als schützenswerte Handlungen (BGE 104 V 19, 24, E. 2; 97 V 72, 29, E. 3). Die Ausübung dieser Sportarten stellt jedoch dann ein absolutes Wagnis dar, wenn die objektiven Gefahren einer alpinistischen Unternehmung so erheblich sind, dass sie praktisch nicht auf ein vernünftiges Mass herabsetzbar sind (vgl. Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 395). Für Beispiele wird auf die einzelnen Beiträge zu den Bergsportarten verwiesen.

bb. Relatives Wagnis

In Abweichung zum absoluten Wagnis knüpft das relative Wagnis an die Art und Weise der konkreten Ausführung eines Ereignisses an. Massgebend ist, ob die versicherte Person alle Erfordernisse (persönliche Fähigkeiten, Charaktereigenschaften, Vorbereitungen, usw.) zur Gefahrenreduktion auf ein vernünftiges Mass erfüllt (vgl. Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 398). Für Beispiele wird auf die einzelnen Beiträge zu den Bergsportarten verwiesen.

d. Rechtsfolgen

Kommt die Versicherung zum Schluss, dass ein Wagnis eingegangen worden ist, kann dies zu einer lebenslänglichen hälftigen Kürzung der Leistungen und in besonders schweren Fällen zu einer gänzlichen Leistungsverweigerung führen (Art. 50 UVV i.V.m. Art. 39 UVG).

Grobfahrlässiges Verhalten führt zu einer zweijährigen Kürzung der Taggelder (Art. 37 Abs. 2 UVG). Die Leistungskürzung oder -verweigerung ist sowohl bei Wagnis als auch bei Grobfahrlässigkeit auf Nichtbetriebsunfälle beschränkt. Dies ist insbesondere für angestellte Bergführer*innen, Skilehrer*innen, Kletterlehrer*innen usw. relevant (vgl. Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 409).

Stellt eine Handlung zugleich ein Wagnis sowie eine schuldhafte Herbeiführung eines Schadens dar, so geht die Leistungskürzung wegen Wagnisses derjenigen wegen Grobfahrlässigkeit vor (Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 407).

3. Insbesondere: Rettungskosten

Die versicherungsrechtliche Deckung der Rettungskosten hängt davon ab, ob die Rettung unfall- oder krankheitsbedingt erfolgte. Für im Ausland geplante Bergtouren empfiehlt sich in jeden Fall der Abschluss einer Zusatzversicherung. Ferner sollten pensionierte Berggänger*innen, welche über keine obligatorische Unfallversicherung (mehr) verfügen, sondern über einen entsprechenden Zusatz bei ihrer Krankenkasse unfallversichert sind, ihre Deckung für Rettungskosten prüfen und gegebenenfalls durch Abschluss einer Zusatzversicherung besser absichern.

a. Krankheitsbedingte Rettung

Die obligatorische Grundversicherung übernimmt bei krankheitsbedingten Rettungen einen Beitrag an die medizinisch notwendigen Transportkosten sowie bei Rettung in der Schweiz 50% der Rettungskosten, wobei pro Kalenderjahr ein maximales Kostendach von CHF 5'000 besteht (Art. 25 Abs. 2 lit. g des Bundesgesetzes über die Krankenversicherung vom 18. März 1994 [KVG, SR 832.10] i.V.m. Art. 27 der Verordnung des EDI über Leistungen in der obligatorischen Krankenpflegeversicherung vom 29. September 1995 [KLV, SR 832.122.31]).

b. Unfallbedingte Rettung

Bei einer unfallbedingten Rettung in der Schweiz werden die notwendigen Rettungs- und Bergungskosten und die medizinisch notwendigen Reise- und Transportkosten vergütet. Weitergehende Reise- und Transportkosten werden vergütet, wenn die familiären Verhältnisse dies rechtfertigen. Im Ausland entstehende Kosten werden höchstens bis zu einem Fünftel des Höchstbetrages des versicherten Jahresverdienstes vergütet (Art. 13 UVG i.V.m. Art. 20 UVV).

c. Rettung einer nicht verletzten Person

Gemäss höchstrichterlicher Rechtsprechung (BGE 135 V 88, zuletzt bestätigt mit Urteil 8C_313/2014 vom 3. Juli 2014) reicht es für eine Kostendeckung nach UVG nicht, dass lediglich eine erhöhte Gefahr für die Gesundheit der versicherten Person vorliegt. Das Gesetz schreibe die Deckung der Rettungskosten nur vor, wenn tatsächlich ein Gesundheitsschaden eingetreten sei. Verlangt werde ferner die Einwirkung eines aussergewöhnlichen Faktors auf den Körper der versicherten Person (wie ein Sturz oder Steinschlag). Dies liege bei Desorientierung oder schlechten Wetterverhältnissen nicht vor.

Zusammenfassend kam das Bundesgericht im Entscheid BGE 135 V 88 zum Schluss, dass eine bloss objektiv gefährliche Situation, aus der sich eine Versicherte Person mit Hilfe eines Helikopters retten lasse, keinen Versicherungsfall im Sinne des UVG darstelle (BGE 135 V 88, 93, E. 3.3; vgl. für eine ausführliche Darstellung Müller, Haftungsfragen, Rz. 415 ff.).